A former emergency room doctor reflects on the long hours, high pressure, and lack of safety nets over his career in China’s medical system

My former classmate, a guy named Shi Liang, used to be a doctor in the emergency department of a major hospital—classified as a “Grade A tertiary hospital,” the highest rank in China. In those days, you could hear him frequently saying things like, “For ER doctors, technique is something we can develop, but our constitution is where our natural talents lie. You see those of us with decades of experience? I’m telling you, those folks got some excellent genes.”

Shi Liang himself didn’t fare too badly in terms of this so-called “natural gift.” His health was decent enough. In fact, back in high school he was the linchpin of our basketball team. Then, he joined the ranks of health care professionals and his circadian rhythms turned upside down for the next seven years. His most intense night shifts had him working for no less than 14 hours; he wasn’t sure how he survived.

Then, at the peak of his career, Shi Liang faced a vital crossroads and ended up hanging up his white coat for good. Everyone was puzzled, but he simply said, “I cherish my life over my job.”

1/7

Shi Liang’s chapter as an ER doctor officially began in 2011, when he started working at a well-known tertiary hospital in a certain northern city.

The head of the emergency department immediately introduced him to the man who was meant to be his direct superior for the foreseeable future—Dr. Zhou. Dr. Zhou was a rail-thin, dark-skinned, middle-aged man with prominent eye bags. In fact, he seemed to be constantly sapped of vitality. Still, he was Shi Liang’s senior, and these were his first words to the young doctor, “You better train yourself to fall asleep as soon as you close your eyes if you want to survive the ER. Sleep is vital here, you hear me? If you let stuff pile up and rob you of your sleep, you better leave the ER as soon as possible.”

That was no problem for Shi Liang. He was young and strong and hit the sack just fine every night. “Insomnia? That’s not a word in my vocabulary!”

Dr. Zhou seemed cautiously approving of this. “That mindset will serve you well, if only you keep it always.” He then pointed to his dark under-eye circles: “I used to think just like you, or at least I did until I hit my 30s. Look at me now, though. I don’t look well rested, do I?”

There certainly was not an idle moment in their ER department. During the peak period, doctors reported seeing hundreds of patients each day. Holidays were even worse: firecrackers gone south, fights and quarrels, chicken and fish bones stuck in throats—just these seasonal incidents alone were enough to fill the entire corridor. On one particularly hectic Lunar New Year’s Eve, Shi Liang handled 173 patients all by himself. He had to speak so quickly he felt someone had pushed a fast forward button on his mouth. It was a struggle for him to keep up until he finally reached the end of his shift. As he did the routine sorting-out of all medical records under his care for the day, only then did he realize that a whopping 16 hours had passed since the beginning of his shift.

The all-too-common truth in hospitals is that working hours on paper rarely match the reality of your actual shift.

Still, Shi Liang was in his 20s then. He oozed stamina and was not acquainted in the least with the feeling of your body being unable to keep up with your will. His own dedication moved him—in his eyes, his neglected sleep and skipped meals were a badge to wear with pride on his metaphorical lapel. He would get himself a pair of sneakers and usually wear the soles down in three months due to all the running around he did in the hospital. His busiest shifts had him awake for 48 hours, but he never went without his basketball games and workout sessions after work. Although Dr. Zhou kept reminding him to “pay attention to his rest,” Shi Liang felt that he was doing just fine. He thought that he’d been blessed with extraordinary comprehension skills and excellent health. He was looking forward to devoting his youth to absorbing skills and experience. A brilliant future awaited him—one where his tireless dedication would no doubt make him stand out among his peers.

—

On a winter night that year, Shi Liang was pulling one of his infamous “double shifts” along with his superior when the ambulance wheeled in a 41-year-old female patient from the county hospital. The woman suffered from an ischemic stroke, brain hemorrhage, and severe renal failure, and had fallen into a deep coma. Her medical records from the county hospital stated the diagnosis as a case of multiple strokes.

Their immediate examination revealed that the patient had a host of issues, including thyroid and electrolyte disorders. Shi Liang found himself facing a wild card when Dr. Zhou asked him to give his input on the patient’s condition. He’d had extensive experience with stroke patients and all sorts of sudden-onset, chronic disease attacks throughout his residence, but it was rare to encounter such a severe case. “This certainly doesn’t look like a simple case of multiple strokes,” Shi Liang replied eventually. “The patient does not seem to be in a deep coma either.”

Dr. Zhou nodded and walked out to relay the news to the woman’s family. Her husband was there, and while he couldn’t really elaborate on all the details of his wife’s condition, he did remember that she’d been down with a cold. She was unable to exert herself for a while, so she had been getting a series of “energy-boosting” injections at their village clinic. That is, until she unexpectedly went into this coma. At this point, Dr. Zhou recalled one of their findings on the patient’s condition and blurted out, “This woman has diabetes. Why was she getting those injections so casually? They’re the equivalent of constant sugar supplements; no wonder she passed out!”

This came as a great surprise to the patient’s husband—he didn’t even know that his wife had diabetes. It was finally clear to Shi Liang: The woman had gone into diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), compounded by multiple strokes. After she passed out, her family took her to the county hospital, where the doctors took X-rays but failed to account for her diabetes. As a result, the woman’s condition had worsened to the point of organ failure.

Faced with this scenario, Dr. Zhou and Shi Liang set on a course of treatment meant to address the patient’s acid-base poisoning as the absolute priority. When she came out of her coma, they would be able to transfer her to the neurology department. Two weeks later, the woman finally turned a corner; she would soon be discharged from the hospital. Shi Liang couldn’t help but feel elated. “Hey, we beat the Grim Reaper once again and cured a complex condition!”

Dr. Zhou, however, didn’t quite share his young disciple’s enthusiasm. The way he saw it, this patient’s case wasn’t complex, and it was a testimony to the limited experience of health care professionals in small, remote areas. Here was a dime-a-dozen story of small-town doctors dealing with a case they might not see once in a lifetime, and treating the symptoms rather than the cause. “Now what if I grow old and incapacitated and I find no experienced doctors around me?” Dr. Zhou ventured. “It’s game over for me, then.”

Shi Liang found Dr. Zhou’s concern relatable. Knowledge and skills were really everything for them. The more he advanced in his own incipient career, the more he felt inspired to give it his all. It was well worth the sacrifice.

2/7

Shi Liang and his colleagues came into contact with all sorts of people in the ER. They were no strangers to the cops from the nearest police station, and they were well acquainted with the their usual clientele—from hooligans to drug addicts, alcoholics, creditors, debtors, and more.

One day, Shi Liang and Dr. Zhou were chatting in the consultation room when a familiar face by the door interrupted them—it was Police Officer Huang. Dr. Zhou gave a knowing wink to Shi Liang and the pair walked out, only to find a middle-aged man lying on the corridor bench with his eyes shut and a network of needle track marks on his arms.

Doctor Zhou’s tone grew sterner all of a sudden. “Not Old Qiao again, for Pete’s sake. What’s up this time? Did he faint after one of his jabs, or did someone beat the crap out of him?”

Officer Huang said: “I reckon he ran out of money again, so he threw himself on the road to see whether he could scam someone by staging an accident. Some real peach here, always learning new tricks, huh?”

Indeed, the man on the bench was no newcomer—either to the hospital or to the clink. Mr. Qiao was a drug addict with a penchant for troublemaking. He was well-known for scuffling with just about anyone willing to get in a fight with him. Then he could extort cash from his opponents to sustain his drug habit.

However, this time he’d seemingly hit a new low, putting himself in proper danger. On the road, an unlucky driver had spotted him and backed a few meters, thinking there was something wrong with him. This was the chance that Qiao had been waiting for—without skipping a beat, he threw himself over the car.

Without any recordings to clear up the situation, the scammed driver could only try and keep the peace with one or 200 yuan. However, Qiao was unexpectedly greedy. He wouldn’t settle for less than 500. The driver tried to reason with him and the scene of the alleged accident grew tense, but Qiao just would not budge. He lay himself on the ground, eyes shut, until his victim had no choice but to call the police.

Thus, Shi Liang followed Dr. Zhao to carefully examine Qiao’s would-be injuries. He turned out to be just fine, other than his usual, chronic health issues derived from his long-term drug addiction—heart and kidney problems, high blood pressure, and limb edema. And yet there he was, motionless and silent despite all prodding, pretending to be dead. Dr. Zhao used up his patience calling his name out a few times. Eventually, he turned around to Shi Liang and said, “Let’s go with a round of furosemide.”

Furosemide, also known as Lasix, is administered to help treat fluid retention and swelling caused by the kind of chronic diseases that accosted Qiao. Interestingly, the drug also doubles as quite the potent diuretic. It acts fast and there’s nothing much you can do to resist the urge to hit the loo once it’s running through your system.

However questionable Dr. Zhou’s decision was from a moral standpoint, it sure did the trick with Qiao. Shortly after getting his shot of furosemide, he started sweating profusely, his face twitching due to the strain of trying to resist the effects of the drug. Everyone watched quietly from the sidelines, until Qiao jumped up all of a sudden, rushing toward the toilet. Officer Huang burst out laughing, “Ah, the call of nature! It won’t spare anyone, not even this shameless guy, huh? Ha!”

Shi Liang was a little surprised. He’d assumed that Qiao would just piss himself, but apparently he still had a modicum of human dignity. Dr. Zhou seemed to have been taken aback as well. His advice to Qiao when he came back from the toilet seemed sincere, “You’re no spring chicken anymore. Count yourself lucky that your little ruse today helped us keep an eye on your health issues. If you go into heart failure you’ll be done with, and for what? Is it really worth it?”

Officer Huang took Qiao away, and the car owner finally let out a sigh of relief. Shi Liang felt a sense of righteousness for having helped the innocent driver, but it was soon replaced by helplessness. It was highly likely that he’d see Qiao back in the ER sooner rather than later.

3/7

During his fourth year in the ER, Shi Liang suddenly experienced severe chest tightness during his night shift. He took off his mask, panting heavily and struggling to take deep breaths. The ever-vigilant Dr. Zhou rushed to take over his patients’ care and told Shi Liang to go take a break right away.

After a while, Shi Liang felt much better. He immediately assumed he’d gone into a little episode of hear irregularity. Yeah, that must be it, he reassured himself. It’s not like he hadn’t seen plenty of electrocardiograms from his colleagues’ practice on each other. In fact, it was far too common a thing for doctors and nurses subject to irregular, demanding schedules that often kept them up way past their bedtime. Older colleagues fared even worse, with gastrointestinal disorders, kidney inflammation, and other problems.

However, Dr. Zhou wasn’t willing to let him get away with just a guess. Shi Liang clocked out in the morning from his shift only to find himself pinned on the examination bed by his superior, insisting that he get an electrocardiogram. Tertiary hospitals register sudden staff deaths from overworking every year, but Dr. Zhou wasn’t willing to have his disciple be a grim statistic.

He asked Shi Liang, “Are you still going out to play basketball after work?”

“No.” Shi Liang replied obediently. “Get yourself home, lie down and rest.”

Shi Liang didn’t dare to disobey Dr. Zhou, or delay paying heed, let alone talk back to him, because he knew that it was all for his own benefit. It’s not difficult to get empathy from a colleague who is all too familiar with your experience. Gaining the same understanding from a stressed-out patient, on the other hand, is a whole other story.

Just to give an example, come peak flu season every fall and winter, doctors and nurses had no choice but to stay in the hospital every day to tend to the sudden influx of patients. At these trying times, while the patients were hooked up to IV drips in the observation room, the doctors and nurses were injecting themselves with the same medicines in the staff lounge. Shi Liang saw countless colleagues pull the IV needle out of their arms and rush out to check on their patients as soon as they were called, but the patients and their families never knew this.

This silence contributed to the common belief that healthcare professionals are these odd, steel-built bodhisattvas with three heads and six arms, immune to sickness and void of any emotions.

—

One winter night, a major highway accident flooded the hospital with injured parties from over a dozen ambulances. For a while, the ER was so crowded that the outer corridors had to accommodate makeshift beds.

Doctors who happened to be off-duty were urgently called to the ward, where they joined their colleagues in frantically working without a moment’s rest. The pace was particularly grueling for those who were in charge of intubating, performing resuscitation, and redirecting patients to specialists. Dr. Zhou, though he was running a fever himself, was busy administering injections in the waiting room. His face was growing pale, but he still insisted on attending his meeting the following morning before finally giving himself an IV injection in the lounge.

However, soon enough they were facing an entirely different kind of emergency. Shi Liang was hurrying from one area to the next when he felt himself slipping all of a sudden. That’s when he realized that the floor was flooded with the water that a man and a woman were taking turns to pour from buckets.

Later, they found out that the pair had acted out of sheer anger—with their relative running a fever, twice they’d asked the nurse for ice packs, and twice she’d failed to deliver them on time, merely because she was overwhelmed with work. The man and the woman lost their temper and went to file a complaint, only to find that most of the administrative staff were off work already. In revenge, they dumped four large buckets of water to “cool down” the ER.

In the chaos that followed, someone shouted: “The equipment! Protect the equipment!” The nurses rushed to take action—some stopped the troublemakers, while others ran to the equipment to drag it away from the water, making sure the power cords stayed dry. However, many of the machines used in an ER can’t really be pulled away from patients, let alone cut off from a power source. The only viable solution was for the nurses to take off their coats to cover the equipment.

Now, it bears repeating that this was a chilling winter night, with ambulances wheeling victims in continuously, the ER being so crowded that the door couldn’t be closed, and the heating out of power. In this disastrous scene, these women all took off their coats and stepped in icy water. Despite their willingness to help, they must have felt wronged by the whole situation.

The police eventually took away the irate relatives and pointed out to them that going out to the nearby pharmacy to buy ice packs would have been a much better use of their time than lashing out. To this, both of them replied that they were already spending money in the hospital. “Just how long would it have taken for that nurse to go and get the ice packs herself?”

After the incident, Shi Liang felt somewhat worn down. A thought crept up on him—were he and his fellow doctors and nurses truly required to sacrifice themselves to their profession? Did they really have no other choice than becoming robots for everyone to constantly beat and scold?

With this thought also came yet another—people should take care of themselves, no matter their job.

4/7

Dr. Zhou had his own burden to carry. He closed one of his night shifts by slipping down the stairs. He suffered a triple fracture on his leg plus gentle teasing from the head of the orthopedics department. “Now, Zhou, remind me how old are you? Osteoporosis at your age already?”

Dr. Zhou was a good sport. The accident was caused by his batteries running low, or so he said with a laugh. “I’ll have you know I haven’t slept a wink for a while.”

Finally, Dr. Zhou’s gloomy complexion made sense to Shi Liang—it was a sign of his ongoing, severe insomnia. Dr. Zhou always enjoyed a good night of sleep in his youth. A few years ago, though, a certain medical dispute sent him into his first anxiety-induced bout of insomnia.

Here’s what happened. A man who had fallen from a building had died immediately after being rushed into the ER. His fall had been fatal—his body had been maimed from the waist down into a gruesome funnel shape. Dr. Zhou gave him a major blood transfusion, to no avail. Relatives seemed to come to terms with the reality of the tragedy and went through all the relevant procedures.

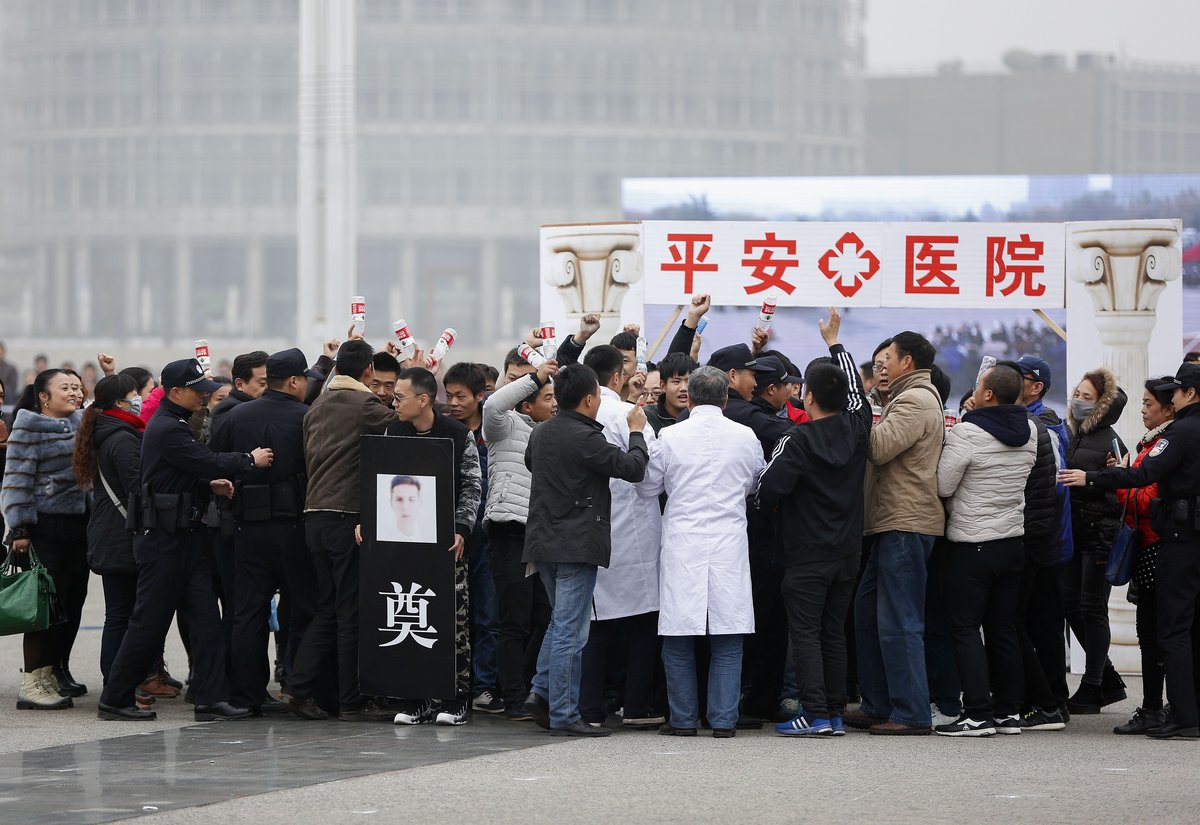

However, a week later the man’s widow decided to make a scene—again, far too common an occurrence in hospitals across China. The woman stormed into the ER with an army of hired thugs, claiming that Dr. Zhou’s “malpractice” had resulted in her husband’s demise. “We demand an explanation!”

The hospital proceeded to review all relevant medical records and logically concluded that Dr. Zhou couldn’t possibly be at fault here. However, the widow was not having it. She stood with the hired thugs every day by the hospital gate, where they blocked the entrance displaying inflammatory big-character posters that demanded a severe punishment for Dr. Zhou and compensation from the hospital. Needless to say, the incident did not go unnoticed. In order to protect Dr. Zhou from the abuse, the head of the ER department determined that he should take a leave of absence for half a month.

“And so my problems began,” grunted Dr. Zhou. “The whole situation went on for a full month, and I was unable to eat or sleep during that time. My mind just kept going back to the tragedy; I spent a great deal of money in therapy. Just imagine; how can you possibly be at peace after someone has tarnished your reputation as a doctor with such a big scandal? I know I really struggled. I just couldn’t let go. I felt angry, I felt wronged. I was a mess with anxiety; I think that incident changed me for good. After this situation, I was no longer able to do anything without agonizing about every single detail. I would hit the sack and start playing the entire day at the hospital back in my mind.”

The angry mob dissipated once they realized that they really would not be able to cash in on their abuse. However, it was too late for the harm that had been done to Dr. Zhou.

From then on, Shi Liang grew afraid as well on behalf of his mentor; he realized that they were only one careless slip on the medical records away from an endless string of disputes. Dr. Zhou, for his part, was quick to point out that the same concern guided their head of department. “When he chases you down for every single damn detail in those medical records? That’s him looking out for his staff. He’s not scolding you. Doctors should always protect their patients, that goes without saying—but they also must protect themselves. The world is full of good people, but there’s also plenty of bad ones out there.”

—

Dr. Zhou left for his hometown to heal from his fracture shortly after his conversation with Shi Liang. In fact, he ended up being on sick leave for more than half a year. When he finally did return to the ER, the first thing he did was file his resignation, much to the surprise of his colleagues.

That night, Shi Liang went out with Dr. Zhou for a drink. His mentor confided that his rare, extended break from the hospital’s constant hubbub had allowed him to finally catch up on sleep. Soon enough, he realized that he didn’t have it in him to return to the chaos. “It’s just really hard to step back into this pace of life after affording yourself this peace of mind. I realized I can no longer be this human trashcan for folks to vent their grievances into.”

Dr. Zhou hurried back to his hometown, where he applied for a job at the county hospital. Taking into account his qualifications and background, he was sure to get the position sooner rather than later. Shi Liang, for his part, couldn’t help but ask Dr. Zhou, “Did you forget about that woman who’d gone into diabetic ketoacidosis? County hospitals are understaffed, lack resources, and experience with cases is limited. You’re not going to find any progress there; quite the contrary. Are you really willing to put yourself in that situation?”

Dr. Zhou patted Shi Liang on the back one last time and said, “Look, I’m 40 years old. It’s okay for me to throw in the towel, if need be. A sound mind needs a sound body, right? I know my salary is going to take a huge cut. But let me tell you this much—the nights are going to be peaceful. I’ve seen how it is at small county hospitals. It’s just so very quiet at night.”

With this, Dr. Zhou waved goodbye. For once, he had a truly relaxed smile on his face.

5/7

Dr. Zhou’s resignation meant that Shi Liang was now a full-fledged frontline doctor. Now, he no longer had a mentor watching his back. He felt this emptiness in his heart. He also gradually realized that he was starting to resemble his mentor. Much like Dr. Zhou in the past, he was now always looking forward to his rest after work, and he also found that his reversed biological clock was starting to catch up on him.

In his fifth year in the ER, Shi Liang started running frequent fevers, particularly after his night shifts. Sometimes, just as he tried to catch up on sleep or meals, his body would suddenly heat up to a temperature of 38.5 degrees. His fever would always clear up the next day after some adequate sleep. Shi Liang knew that he had his youth to thank for being able to bounce back so quickly, but in his heart of hearts, he knew that his recurrent fevers were a sign of his immune system declining.

His wife was greatly pained to see this; she repeatedly tried to persuade him to step down. “Your health is more precious than your career.” However, Shi Liang was still unable—no, unwilling—to resign. The ER provided the perfect environment for him to truly fulfill his potential. Nowhere else would his skills be tempered to the maximum. And, it wasn’t only about his career development; his job was handsomely paid and came with great social status and sense of worth. His dotage still a while away; he didn’t want to waste the prime of his life.

And so, husband and wife were unable to find common ground—until Shi Liang had a true wake-up call in the shape of a patient.

—

Even by the usual standards of a double night shift, it was still intensely busy that one night. The ambulances brought in so many patients that they spilled into the corridor, making a big fuss. Then, a middle-aged man, likely in his 50s, made it to the ER alone. He reeked of alcohol, and at first Shi Liang assumed that he was yet another drunkard in seek of a jab after drinking one glass too many.

The man’s speech was coated in a thick southern accent. He had treated himself to a serving of spicy snails, a famed delicacy in his hometown, or so the man swore. He’d boiled the snails himself, too. Here, Shi Liang thought of the edible snails he’d seen in their inland, northern city, but none matched the man’s description. With this in mind, he asked the uncle whether he’d perchance eaten rotten snails, but this much the man negated waving his hands plenty. No, no way. They were alright. He’d boiled them himself, after all...and his fellow villagers all indulged in this treat...really delicious...

At this point, Shi Liang was pretty certain that the guy had a mild case of food poisoning, so he got him hooked to an IV and made him drink milk to induce vomiting. Little did he expect that only half an hour later, the man would suddenly stop breathing. The deputy head of department was called and listened calmly to Shi Liang’s detailed description of his patient’s issues; he hailed from the south himself and was able to identify the snail species that the uncle had consumed right away. They got the man on a ventilator immediately, administering the appropriate treatment for his symptoms, and finally his breathing resumed and went back to normal.

This incident with the poisonous snails left Shi Liang riddled with lingering fears. He thought that the man himself should know better than eating whatever he pleased, for his own sake. Unfortunately, this was far from being the case. Not long after his first visit to the ER, the uncle was unexpectedly back. To top it off, he had eaten the exact same species of toxic snails again. “Well, I really did give it some thought,” the man said. “You see, I thought that the last time I hadn’t cleaned them up good enough, so this time I took care of that and I cooked them for a bit longer. Who’d have guessed that it still wouldn’t work, huh?”

Shi Liang looked at his stubborn patient and realized that doctors, while able to cure physical diseases, cannot really reach the mind of their patients. When a patient is too hard-headed to pay heed to the doctor’s advice, it’s only a matter of time until they land back in the ER. This time it was a case of food poisoning; the next time it would be the sugar that a diabetic was not willing to give up, or the cigarettes that someone suffering from lung disease refuses to quit. Unable to control their desires, these people pinned their hopes of recovery and health on their doctors.

Shi Liang took it upon himself to scold the man when he was discharged from the hospital: “Uncle, if you don’t change your ways, you’ll be back. Just don’t come on my shift, alright? By now we all know how to deal with you, so any doctor will do. Don’t come bother me, okay?”

The man didn’t take offense. He smiled shyly and promised to try and behave.

Back home, Shi Liang shared the incident with his wife. Much to his surprise, she replied, “I mean, you’re just as stubborn as he is. You know full well that you’re running yourself ragged with work, and yet you won’t stop.”

Shi Liang’s resolve quivered. He didn’t reply but he struggled to sleep that night, too.

6/7

One afternoon on a day off, Shi Liang’s wife found a lump on his back. It hadn’t been quite as apparent when he stood up straight, but now that he was bending over to put on his shoes, it was there alright, the size of a steamed bun on the right side of his spine. His wife interrogated him in disbelief: “Why is it so big? When did it first pop up?”

Shi Liang hurried to the hospital for an ultrasound examination, and the results were clear—it was a spinal tumor that made the doctor sigh with worry. “Goodness, I’ve never seen such a large one in this area.” Shi Liang’s wife just about dropped dead at the news, panting at the thought of losing her husband. Their baby had just turned 1. Whatever would they do, mother and son, if Shi Liang died?

Shi Liang’s own medical experience told him that it was extremely rare for a tumor to grow directly on the spine. Spinal tumors tend to be metastatic, but this was highly unlikely in his case considering that he was in no pain at all, without any other sign of discomfort indicating that the lesion could have spread to other organs. He rushed his wife back into their car, heading to another hospital for an additional examination. In the end, it took a total of two major hospitals and a full set of tests for them to breathe a sigh of relief. Indeed, the tumor was close to the spine, but it was benign. It could be easily removed without any complications.

After this fortunate conclusion, Shi Liang found himself in the grip of his wife’s tearful hug as she begged him to quit. Shi Liang remained silent. He’d been in the ER for seven years now. Was he really going to desert his unit now?

—

In any case, Shi Liang didn’t want his colleagues to find out about his health issues, so he went to work as usual before his surgery. During yet another of his intense night shifts, he got to be in charge of resuscitating a critically ill patient. However, his pushing on the patient’s chest gradually weakened after a short while. At this moment, a young doctor who was on rotation suggested taking over. “Let me take charge!”

Shi Liang agreed, but just as the pair changed positions, a man burst into the ER, raised his fist, and slammed it into the young doctor’s head. Everything happened without warning—the young doctor was defenseless and fell to the ground. Shi Liang was stunned. Had he stayed by the bed for even half a minute longer, it would be him on the floor.

A swarm of security guards, nurses, and patients’ family members from all over the ER rushed over to pull the attacker away. The reason behind his outburst remained unknown—they believed it was an indiscriminate attack, meaning that he’d just assaulted the person who was nearest to the entrance. The young doctor suffered a slight concussion, but his colleagues had no time to spare for anger; they continued assisting the critically ill patient.

It was at this moment that Shi Liang’s doubts finally cleared up.

7/7

A week later, it was time for Shi Liang’s tumor resection surgery at another tertiary hospital. He was only under local anesthesia, so he got to talk to the chief throughout the surgery. Only, Shi Liang lied when he was asked about his occupation. He said that he was an employee at some company. The doctor then asked, “Are you doing tons of overtime? You better drop that. It’s harmful for the body to have such irregular work and rest patterns.”

“What about you?” Shi Liang asked back.

The chief surgeon fell silent for a moment. “Hey, now, don’t be so hard on me! Doctors don’t get the luxury of that choice. Do as I say, not as I do.“

Later, as Shi Liang recalled his surgery with his wife, he couldn’t help but roast the surgeon on account of his slow, rigid ways with the scalpel: “I could have shown him a few tricks. Snip, snip—I’d have been done faster and with much better technique.”

His wife replied, “Well, he’s still gonna beat you with his good health and stamina.”

All in all, Shi Liang made it out of his health scare with a long scar on his back as a souvenir. In mid-2019, he reluctantly hung up his own white lab coat for good.

After his resignation, he met up again with Dr. Zhou for another drink to catch up.

Shi Liang told him about his growth. “Luckily, it was benign, otherwise I wouldn’t be here tonight. You know, you were right—in my youth, I had all these grand plans. Then I grew older and the comfort and survival of my earthly flesh beat out all my lofty aspirations.”

Dr. Zhou let out a drunken laugh. “Ideals come with small print and requirements, too. The hospital is still doing alright even after you left, isn’t it? Look ahead of you. Wanna guess my bedtime nowadays? 11 o’clock.”

—

Though Shi Liang left his demanding job at the hospital, he did not leave the medical industry altogether. He got a job selling medical devices. The benefits were numerous—weekends off, annual leave, travel, family reunions during the holidays...

However, Shi Liang did still experience significant pressure from the fierce competition in his new line of trade. The outside world wasn’t as rosy as he’d envisioned, and no industry will make it easy for you to make money. His new occupation relied greatly on contacts, though fortunately Shi Liang had a solid network from his seven years of experience in a major hospital. There was still a difference, though. As a doctor, he was the one people were flocking to do business with. Now, he was running around begging people to give him the time of day.

After his resignation, a great deal had changed in his previous department at the hospital. A new administrative board took over, vowing to clean up the department and expose previous wrongdoings. Nobody was safe. Shi Liang got quite the sudden message one day from a former superior. The man himself had fallen out of grace with the new board, and begged Shi Liang to help him save face by becoming a scapegoat for some error. After all, this doctor reasoned, Shi Liang had stepped down already. “I will pay the fine, of course, but if I get blamed for the whole thing, I can kiss goodbye any promotion for the next eight or even 10 years. None of the legal proceedings will affect you in any way whatsoever.”

It’s not like Shi Liang could really refuse. His current occupation depended entirely on contacts from his years as a health care professional. He could not afford to alienate anyone from his former department. However shameful this whole situation was, Shi Liang had to take the blame for his former superior.

At the beginning of 2020, when the pandemic first broke out, some of Shi Liang’s former colleagues set off to assist hospitals in Hubei. Shi Liang brooded—now he really did feel like a deserter. “Had I known this would happen,” he lamented, “I would have weathered the storm for two more years. It’s really hard for me to come to terms with the fact that I didn’t have what it takes to be a doctor.”

Even if his support was limited to running errands, Shi Liang wanted to do his part in the fight against the epidemic. The hospital was running short of supplies at the beginning of the crisis, so he turned to his network of suppliers to divert masks and alcohol. When some medical staff were quarantined in the hospital at the very peak of the outbreak, Shi Liang resorted to his contacts again to handle their meal delivery service.

As for the ideals of his youth, this is what Shi Liang has to say: “A person has to have some aspirations. Whether it’s worth it or not, I try not to dwell too much on it all. I made the best choice that was available to me at the time. If you realize that you’re not cut out for living a constant fight, it’s best to just live an honest life, on your own terms. It’s called living your own life.”

All names in this story are pseudonyms.

Written by Kui Kui (魁葵)