Liaodi Pagoda, once the tallest structure in the world, now stands as part of the backdrop of a crowded square in a small Hebei city

A towering structure casts a diminutive shadow over Dingzhou’s cultural plaza, a town square of sorts in this county-level city within Hebei province. This silent stranger is strikingly tall at 83.7 meters in height and stands proudly like a stoic guardian of the land, but few people acknowledge its presence.

The Liaodi Pagoda, constructed between 1001 and 1055 CE during the Song dynasty, could be called China’s first skyscraper. Remarkably intact after almost a millennium, it was once the tallest building in the world and remains the tallest ancient brick tower in China to this day. It’s also known as the Kaiyuan Temple Tower, but the eponymous temple surrounding the pagoda has diminished over time and ultimately disappeared, leaving precious little of the original complex behind.

On this Lantern Festival, the first after the pandemic, most visitors and locals in the square are far too preoccupied with sizzling skewers and ring toss games to even consider looking upward. After following a maze of side streets and back alleys, an elderly man points me to the ticket office of Liaodi Pagoda. I’m surprised it isn’t more packed; the pagoda itself features frequently on city flyers and tourism propaganda, but I soon find out why: At 17:00, the site has been officially closed for thirty minutes.

I set my alarm for the following morning, and wait as night washes over the city. The Lantern Festival is in full swing, visitors and locals alike seem to be making up for lost time during the pandemic. The bare branches of the trees lining the city’s streets and avenues bulge with neon lanterns, gift-shaped ornaments, and traditional red envelopes. I’m confronted with teams of karaoke singers on the street who are braving arctic winds to belt out a tune. A brilliant burst of light illuminates the night sky, and I hear a crackling sound, like popcorn in a pan, that reaches a crescendo of intensity as vibrations reverberate through my chest and leave me feeling tingly. I offer up a shaky laugh, realizing that these are my first fireworks in almost three years since Covid-19 first struck China.

—

The next morning, I rush out before 8 wanting to ensure I can buy a ticket before the crowds. Shockingly, I’m the first tourist to enter Liaodi Pagoda for the day. “We occasionally get school groups and university outings,” says the cashier, who introduces himself as Yifan. “But not at this time of the year.” The “historic town” (a newly built reconstruction) that sits immediately adjacent to this legitimate piece of history receives far more fanfare.

I glide past the small museum that traces the timeline of the pagoda immediately adjacent to the ticket office while noticing a collection of columns and pillars that bear the moniker of the “Japanese War of Aggression.” Evidently, these artifacts were defaced during the widespread ransacking of China during the Japanese invasion and remained buried under mounds of rubble for decades, until they were found by a farmer plowing his fields.

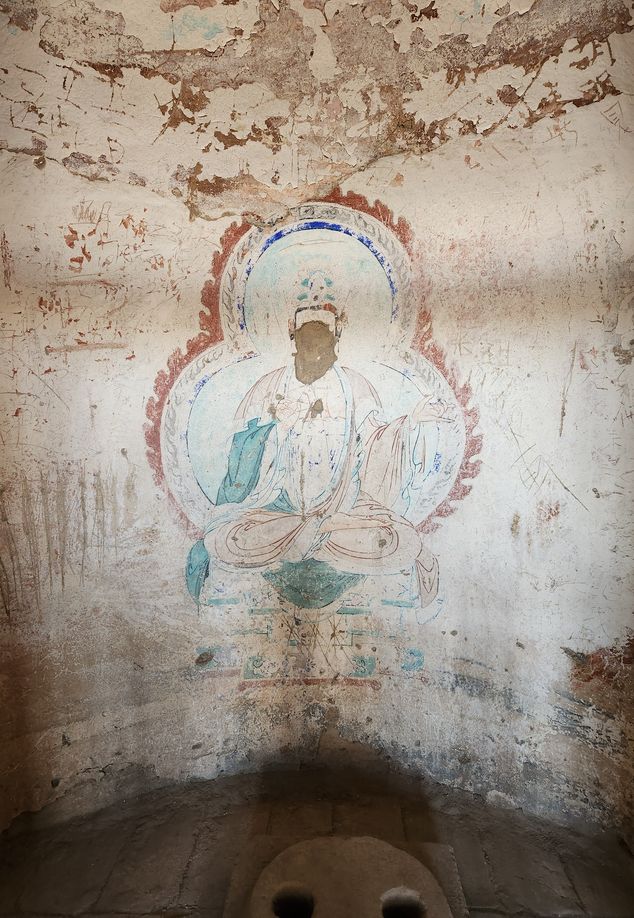

Murals inside the Liaodi Pagoda have survived hundreds of years and multiple armed conflicts (RJ Fry)

As is appropriate in Buddhist practice, I circle the pagoda clockwise. Three-quarters of the distance around the tower’s base, I spot an open door and a man wearing a drab olive-green overcoat lets me in. “It’s a steep climb. Are you in good health?“ he enquires. Rather than wait for an answer, he lights a cigarette and shuffles out of sight.

The first flight of stairs looks more like a tunnel than a stairwell; I manage to bump my head two or three times before realizing it would be better to treat this set of steps more like a ladder. Both the walls and the stairs are cool to the touch, almost unnaturally smooth.

The first floor is home to the central Buddhist altar. A plaque on the wall informs visitors that it once housed an enshrined sculpture of Buddha before it was looted and destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. A wishing well of sorts has popped up in its place; the familiar light green hue of one renminbi notes reigns supreme as light filters through the umbrella dome ceiling overhead.

On each successive floor, remnants of original artworks and calligraphy decorate the cement walls. The colors are remarkably full, given their age and neglect, and are kept safely behind glass screens. As one of numerous plaques and posters throughout the complex and museum stated, “The tower of Kaiyuan Temple has suffered a lot in thousands of years” but “in 1988, the Kaiyuan Temple Tower was formerly restored, repaired and reinforced.” My gaze lingers on a mural depicting a man and a dog, with the eyes of the canine remaining firmly fixed on me and inviting me to cross a bridge and embark on a journey through time and space.

Buddhist shrines and altars can be found on each ascending floor, highlighting the religious and spiritual significance of this building; while some paintings have still retained the outline of Lord Buddha, most have become palimpsests of scrawled messages and vandalism. The Cultural Revolution took its toll on this structure, as the walls are inundated with graffiti tags, murals, and splashes of color. The statue of Lord Buddha on the first floor was destroyed, and all painted murals of him on subsequent floors have either been painted over or left to deteriorate over centuries. A circular corridor connects both inner and outer towers on each level, with the 11th story being cordoned off to visitors. As such, the 10th floor becomes the viewing platform by default.

Legend has it that upon reaching the summit of Liaodi Pagoda, one can view the blue sea in the east and the tiger-shaped Jia Mountain in the west. While mountains are definitely visible, a great distance separates Dingzhou from the sea, making it impossible to see the ocean from my vantage point. This pagoda once served as a lookout during the Song dynasty when Dingzhou was an important military base near the frontier between the Song and the Khitan Liao Empire to the north, hence its name, Liaodi (料敌)—”observing the enemy.”

The Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1126) is regarded as an apex of prosperity in Chinese history. An abundance of food—particularly due to the acquisition of a Southeast Asian rice variety, known for producing higher yields—allowed emperors to shift their focus from military matters to improving the lives of civilians. In addition, it was during this time period that much of the stigma and shame associated with commerce was removed, and the world’s first paper currency, known as jiaozi (交子), came into being, sparing travelers and traders the burden of carrying heavy coins and precious metals. Three of the “four great inventions” of ancient China were mastered during this time period: gunpowder, movable-type printing, and the compass.

Skyscrapers will forever be linked to wealth and power, whether it be the Burj Khalifa or the Shanghai Tower. Perhaps it makes sense that the tallest building in the world during the eleventh century would be located in Dingzhou, even if it is now a county-level city that has since been overshadowed in size by neighboring Baoding and Shijiazhuang. Dingzhou’s population today exceeds one million people, but interestingly enough, the population almost reached that as far back as the Sui dynasty (420 – 589), when it registered 834,211 residents.

It’s easy to get lost in the past and imagine Liaodi Pagoda in its heyday; the remnants of scripture, calligraphy, and artwork that can be found on each floor hint at the majesty it once proclaimed to the world. It remains important for more than just religious reasons, as it has come to symbolize a catalyst in Chinese craftsmanship and the engineering capabilities of that time period.

The temple’s colorfully painted dougong (斗拱)—interlocking wooden brackets that are a vital component of traditional Chinese architecture—are now considered cultural treasures and crucial heirlooms from the Northern Song dynasty. Once upon a time, the exterior of the pagoda was encased in gold leaf (like many stupas and pagodas throughout Thailand and Myanmar) and contained an interior that showcased a mosaic of style, art, and thought. While some imagination might be required to fill in some of the gaps now, it’s remarkable that it remains in such good shape nearly one thousand years after it was constructed.

The tower has not only survived the plundering of its paintings and sculptures by the Japanese invaders and the Cultural Revolutionaries, but also the wrath of nature. In 1720, a quake shook Dingzhou and broke the holy vase on top of the tower into three pieces. More than a hundred years later, in 1884, decay had weakened the structure and caused the northeast corners of several levels to collapse, leaving a quarter of the tower in ruins. Shakespeare might have called it “besmeared by sluttish time”, but I think it is amazing that this structure still stands defiantly against the ravages of time.

Looking down on Dingzhou and the busy laneways of the Ancient Town, I’m surprised I’m not being pushed back and forth by the ebb and flow of a raging sea of sightseers. Indeed, one of the more curious elements of this landmark is how peacefully one can peruse its history. In fact, it isn’t until I descend from the tower itself and visit the small museum onsite that I encounter any other visitors.

“Most locals take it for granted,” a visitor at the museum, who introduces herself as a local called Zhao Qing, tells me. “Everyone who grows up in town has visited on a school trip; it’s basically a rite of passage.”

Like the Statue of Liberty in New York City, or Tiananmen Square in Beijing, most of the tourists at such sites are non-locals seeking opportunities to have some one-on-one time with one of the world’s first skyscrapers.