From veiled scholar hats to canopied backpacks, China’s obsession with sun protection is not a recent one

As record-high temperatures roast the Northern Hemisphere for yet another summer, Chinese people’s fastidious (and disturbing) methods for sun protection are again on display.

But whether it’s swimming in infamous “facekini” or wearing head-to-toe covering on sweltering days, China’s obsession with sun protection is a not recent one.

Since ancient history, where a proverb stated that “white skin covers a hundred blemishes (一白遮百丑),” paleness has been a prized physical characteristic that marked a person as high in social status, as it meant they didn’t have to toil in the sun. Consequently, ancient Chinese had various ingenious methods to protect themselves against sunlight and heat:

Ancient sunhats

There were many different types of sunhats in ancient times. One wide-brimmed kind woven of rattan, called 席帽 (xímào, rattan hat), was very popular. In his book Annotation to Past and Present (《古今注》) recorded in Jin dynasty (265 – 420) scholar Cui Bao (崔豹) wrote that “both men and women wear it.” Later, rattan sunhats became fashionable. Song dynasty (960 – 1279) scholar Wu Chuhou (吴处厚) stated in his book Miscellaneous Records from Knowledge Across Generations (《青箱杂记》) that scholars “always take a woven rattan sunhat with themselves.”

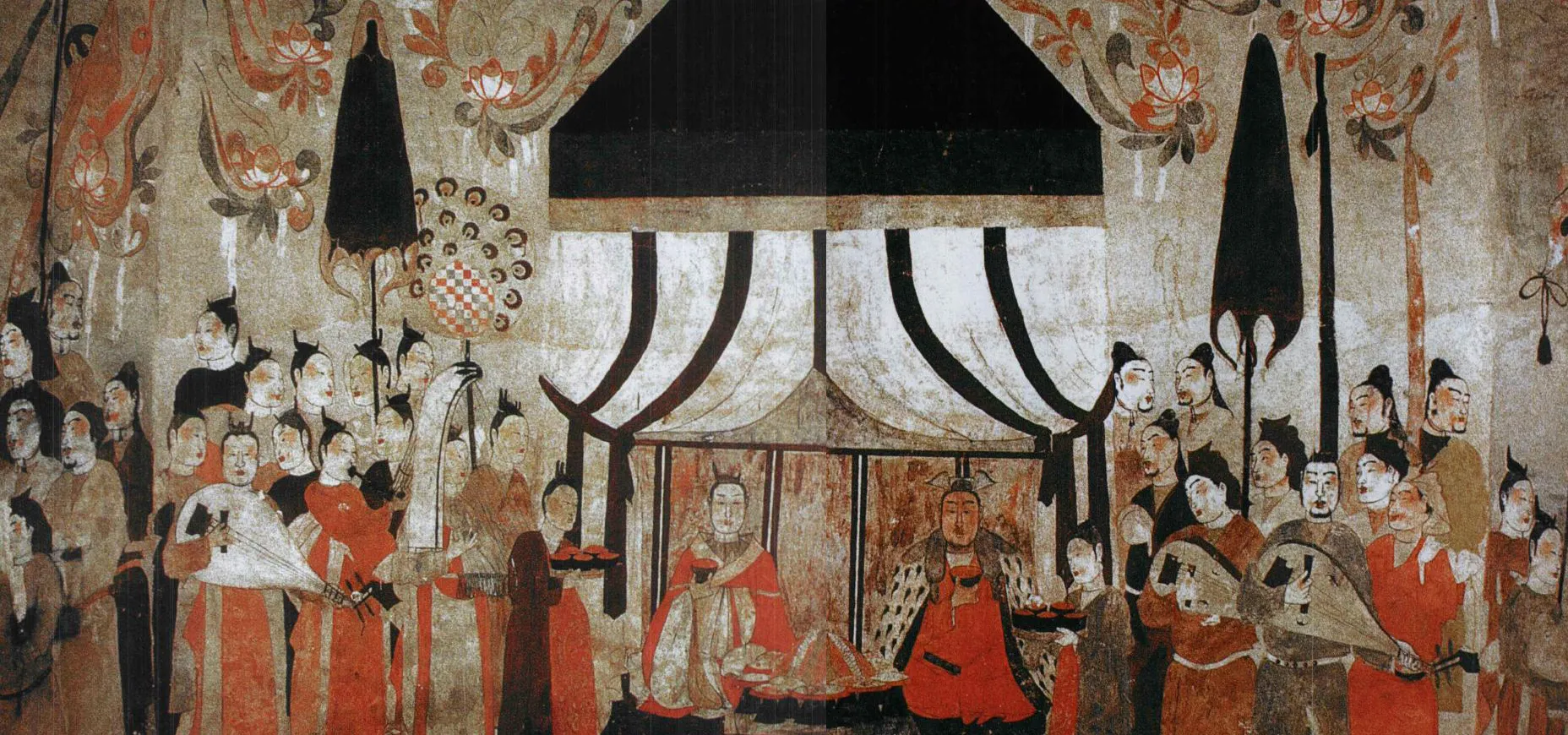

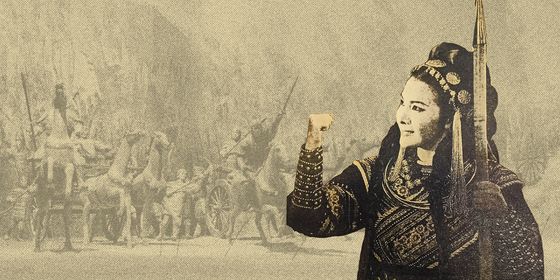

In the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), a sunhat with a shoulder-length veil gained popularity. It was called 帷帽 (wéimào, curtain hat). The weimao evolved from the 幂篱 (mìlí), a hat attached with a body-long veil. Due to the liberal social atmosphere of the Tang dynasty, veils became shorter, and the weimao gradually replaced the mili. Weimao was also called “Zhaojun Hat (昭君帽)” because Wang Zhaojun (王昭君), one of ancient China’s famous beauties, wears one in the “Painting of Zhaojun Leaving the Frontier (《昭君出塞图》)” by the great Tang painter Yan Liben (阎立本), though Wang had lived centuries before weimao were to emerge.

In historical texts from the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), sunhats were referred to as 遮阳大帽 (zhēyáng dàmào). In an encyclopedia called The Collected Illustrations of the Three Realms of Heaven, Earth, and Humanity (《三才图会》), it’s recorded that Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), the founder of the dynasty, once visited the imperial college, and all the students stood under the sun waiting for him. Feeling sorry to see the men sweating under the sun, the emperor ordered his courtiers to give each of them a sunhat. After that, the sunhat soon came into fashion among scholars.

Canopied backpack

Besides sunhat, ancient people also used backpacks to shelter themselves from the sun. The backpack was called 书笈 (shūjí, book box) or 行笈 (xíngjí, travel box). What distinguished it from a regular knapsack was that there was a covering above it that could shelter the person. Travelers, especially scholars, often carried such a backpack on their trip, since the covering could both protect them from the sun and the rain. One could even hang a lamp under the covering, in order to shed light on the road at night.

Imperial canopy

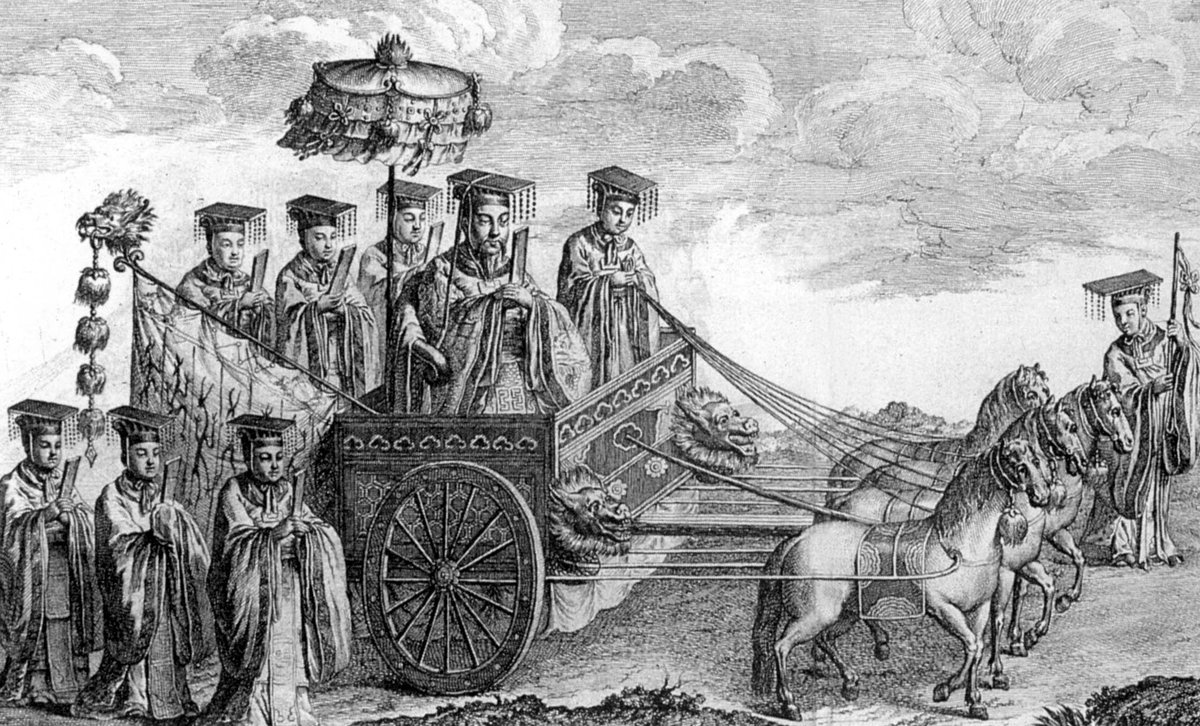

In ancient times, when the emperor or high-ranking officials went on a journey, servants would walk alongside their carriage and hold a huge canopy over them. This was called 华盖 (huágài). It was invented to protect the emperor from the sun, but that wasn’t because the emperor was afraid of getting tanned. Instead, ancient people believed that the emperor was so exalted that the sun shouldn’t be allowed to shine directly on him.

Cui Bao claimed in Annotation to Past and Present that huagai was invented by the Yellow Emperor (黄帝), the mythical ancestor of Chinese people. It was said that when the Yellow Emperor was fighting against his rival Chiyou (蚩尤), there were always colorful clouds forming beautiful patterns over his head. After the battles, the Yellow Emperor made a canopy to imitate the clouds, which symbolized good luck.

Gradually, the huagai became a symbol of imperial power, and was given new meanings. Some say it signifies that the ruler would shelter all the people under heaven. In dynasties like the Qing (1616 – 1911), if a beloved regional official was about to leave office, the local people would send him a canopy with many silk strips hanging from it to show their respect. This was called the “umbrella of all people (万民伞).”

Sun-blocking architecture (and cooling parties)

Traditional Chinese architecture often had overhanging eaves, known as 挑檐 (tiāoyán). The eaves could effectively block out the sun, so that people inside the house wouldn’t be exposed to sunlight directly.

The windows were also specially designed. Especially in the Ming and Qing dynasties, there was a type of window called 支摘窗 (zhīzhāichuāng, “window that could be propped up and closed”). When the window was propped open with a stick, it formed an angle that shielded the house from strong sunlight.

What’s more, wealthy people often grew plants like bamboos or Chinese bananas in the yard. Their large leaves created shade. If they couldn’t grow plants, some people built tents and summerhouses outdoors. According to a book called Records of the Four Season Scenes in Hangzhou (《四时幽赏录》) by Gao Lian (高濓) of the Ming dynasty, in the city of Chang’an (present Xi’an in Shaanxi province), people erected canopies in the garden and held “cooling parties (避暑会 bìshǔhuì)” under them.