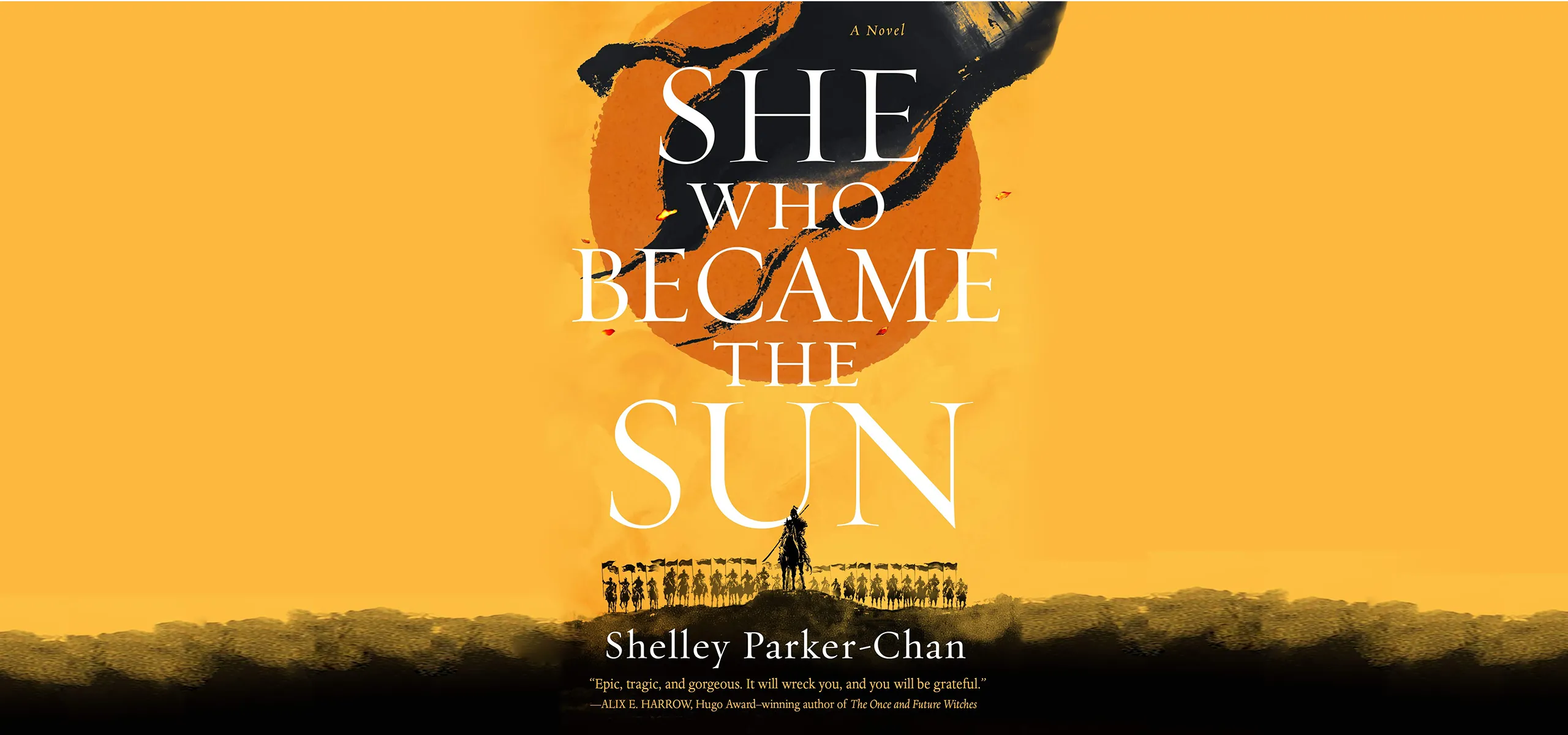

Asian-Australian author Shelley Parker-Chan’s “She Who Became the Sun” may not be historically accurate, but that’s not the main reason to read it

There ought to be a rule for reviewers of historical fiction, especially novels set in ancient China: Whether the novel is “historically accurate” doesn’t matter.

The past can be a powerful point of departure. Setting a story—even if it also includes fantasy elements—in an actual historical period merely saves the author from the exhaustive task of world-building, while providing rich opportunities for fun Easter eggs that will delight historically informed readers.

She Who Became the Sun is the first in a duology by award-winning Asian-Australian author Shelley Parker-Chan and is loosely based on the rise of Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), who founded the Ming dynasty in 1368. Parker-Chan takes liberties with certain characters, most notably making the protagonist not the historical Zhu but his fictional genderfluid sister, who assumes his identity and proceeds to reshape history.

Like in a good Marvel movie, those who have “read the book” (i.e., are familiar with the legends and stories of Chinese history) will have fun identifying who is who, and which plot twists depart from the historical record, while those who are less up on their Ming chronicles will still enjoy a ripping good yarn. Parker-Chan’s website includes a crib and links to the actual biographies of some of the protagonists and antagonists, and fantasy fans who can work out the tangled Targaryen family tree on House of Dragons won’t have any trouble diving into the chaotic world of China in the 14th century.

The real Zhu Yuanzhang was born Zhu Chongba to a poor family in central China in 1328 during a time of civil war, famine, economic upheaval, and chaos. As a young boy, Zhu was raised in a monastery before joining a branch of the Red Turbans, one of the many rebel groups seeking to overthrow the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty in China. Through skillful politicking and battlefield success, he rose in the rebel ranks and attracted a core of loyal followers and officers. After defeating rival rebel leaders in a series of epic campaigns, he forced the Mongol rulers out of China in 1368 and established a new Chinese dynasty, the Ming, with an imperial capital in Nanjing.

Historians generally regard Zhu Yuanzhang as a cunning and often ruthless leader. He was the first person in the 1,000 years since Liu Bang (刘邦) established the Han dynasty in 206 BCE to rise from a commoner background and become the emperor of a major dynasty, something that is difficult without skill, luck, and ruthlessness. In his later years as emperor, this ruthlessness would devolve into cruel paranoia and a remorseless need to expose and punish disloyalty. Many of Zhu Yuanzhang’s former friends and allies suffered from the emperor’s latter-reign fits of cruelty and capriciousness.

The protagonist of Parker-Chan’s novel has much in common with this historical Zhu Yuanzhang, and the story is similarly set amidst the turmoil which erupted in China at the end of Mongol rule. The Zhu family’s eighth son seems destined for great things, but his untimely death breaks the timeline and presents an opportunity for his sister, who is never given a name of their own, to assume their brother’s identity in order to get food, shelter, and sanctuary in a local monastery (the author uses “they/their/them” pronouns, which will also be used in this review for the main character, though Parker-Chan also plays with the nuances of gender identity by using both male and female pronouns according to how the protagonist is perceived by other characters).

Through skill, luck—and not a little budding ruthlessness—the sister, now embracing the name of the deceased Zhu Chongba, moves up the monastic hierarchy, becoming a favorite of the abbot, at least until the monastery is destroyed by the Mongols. Along the way, Zhu befriends future ally and real-life military leader Xu Da (徐达), portrayed in this novel as a wayward hunka hunka burnin’ monk.

Though the central twist of this novel is that the person who founded the Ming dynasty was not the real Zhu Yuanzhang or even somebody who was born male, Mulan this is not. The plot unfolds through a nuanced evolution of gender fluidity that also plays a major role in the development of Zhu as a protagonist. In an interview with the book website The Quiet Pond, Parker-Chan said, “You’ll find my feelings about being genderqueer; my anger at how Asian-Australians have been mocked and othered by white Australians; my rage at being coded female in a misogynistic society. They’re all in [this book], mixed and matched and transformed by analogy and metaphor.”

Zhu Chongba is not the only character whose journey is partially defined by issues of identity, gender, and sexuality. The decades-long occupation of China by the Mongolians means that several notable characters are liminal figures, straddling the ethnic and cultural divide between Han and Mongol. One of the novel’s primary antagonists, Ouyang, is a Han eunuch in service of Esen, a fictional son of Chaghan Temur, a real-life Yuan general known as the “Prince of Henan.” Ouyang has reasons to hate the Prince of Henan, but this enmity is complicated by Ouyang’s relationship with his master/crush, Esen. Ouyang harbors a secret that could destroy Esen’s whole world and yet finds himself—for reasons of loyalty, ambition, and lust/love—serving his Yuan enemies.

Since She Who Became the Sun is the first part of an announced duology, Zhu Chongba presumably goes to the dark side at some point. This development is teased in the later chapters. The book concludes with Zhu Chongba assuming the name Zhu Yuanzhang, taking command of the Red Turban armies, and preparing for a showdown with their rival Chen Youliang, the final war against the Mongolian rulers, and then becoming the emperor of the Ming dynasty. As emperor, the career of the historical Zhu Yuanzhang did not work out well for his former supporters and friends, notably Xu Da.

The moral center of this novel, and witness to Zhu Chongba’s transformation from monk to monarch, is Ma Xiuying, the future empress. She and Zhu Chongba have a romantic relationship and marry once Ma learns Zhu Chongba’s secret. In fact, some of the scenes between the two are imaginative and descriptive, putting this novel more in line with George R. R. Martin’s bedroom sensibilities than those of J. R. R. Tolkien or J. K. Rowling.

Like most epics, some sections drag a bit as key figures are moved around the map to set up suitably dramatic encounters. Nevertheless, Parker-Chan is a gifted storyteller who makes the most of their material. Whether that material is historically accurate doesn’t matter in the least. In China, television and movies have long drawn on historical sources blurring the lines between real-life figures and pop-culture icons. Parker-Chan’s novel is not history, and it doesn’t need to be. It uses historical sources as the foundation for an epic tale while providing exciting twists and surprises which should amuse and delight even the most pedantic historian.