These women were wrongly blamed for bringing down dynasties

When the long-awaited mythical blockbuster Creation of the Gods finally hit cinemas in July, it brought a storm of debate over a fox spirit with it.

Based on the Ming dynasty fantasy novel Investiture of the Gods (《封神演义》) from the 16th and 17th centuries, the epic story of the fall of the cruel King Zhou of Shang raked in over 1.8 billion at the box office between July 20 and August 10.

But its portrayal of Daji (妲己) piqued special interest online. Historically, she was a concubine of King Zhou. But more famously, she was a fox spirit occupying a woman’s body in the novel, both seductive and wickedly dangerous—often blamed for decadence and the collapse of the dynasty over 3,000 years ago.

In Creation, however, Daji is an innocent animal who does not understand the concept of good and evil, and her beauty is no longer blamed for political upheaval. The Weibo hashtag “The new Daji in Creation of the Gods is finally not a wicked beauty who brings trouble” has received over 10 million views at the time of writing.

Daji is not the first woman to be wrongly blamed for dynastic downfall. There are even numerous idioms to describe the dangers of attractive women to political stability, including 红颜祸水 (hóngyán huòshuǐ, dangerous beauty) and 女色误国 (nǚsè wù guó, a woman’s charm can endanger a nation).

Xi Shi, now considered one of the “Four Great Beauties” of ancient China, was shamed for centuries for apparently using her beauty to bring down the State of Wu during the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE). But Tang dynasty (618 – 907) poet Luo Yin (罗隐) mocked this theory in a poem nearly 1,000 years later: “If Xi Shi knew how to bring down the Wu kingdom, then who made the Yue kingdom fall?”

Here are three more scapegoated women of history, whose reputations deserve to be reformed:

Moxi 妺喜

The Commentary of Zuo (《左传》), a narrative history written between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE, really tried to pin the blame on women. It argued that the Xia dynasty ended with Moxi, the Shang dynasty with Daji, and the Zhou dynasty with Baosi (褒姒).

Moxi was deemed exceptionally indulgent and evil. Originally a princess in the small State of Youshi, she was offered as a gift to King Jie of Xia (2070 – 1600 BCE) after his troops defeated her home state. According to Records on Emperors and Kings (《帝王世纪》), Moxi found delight in the sound of silk, a luxury fabric at the time, being torn apart. King Jie used to drink with Moxi and other court women all night, often placing Moxi on his knees and doing whatever she asked him to do.

Han scholar Liu Xiang’s (刘向) Biographies of Exemplary Women (《列女传》), a historical record of women’s stories possibly dated back to the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), even records that Jie created a wine-filled pool and invited 3,000 people to drink from it, while Moxi laughed as she watched drunk people drown to death.

Meanwhile, Bamboo Annals (《竹书纪年》), a history text dating back to the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), blames not just Moxi’s seduction but her jealousy. After Jie began to favor other women over her, Moxi supposedly became resentful and plotted with King Jie’s enemies to overthrow the Xia dynasty in 1600 BCE.

But these scandalous records are unlikely to be the whole truth. Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) describes Jie as an oppressive ruler who had estranged his dukes and harmed his people, dooming his dynasty on his own. While much late, in the 1980s, writer Bo Yang described Moxi as a miserable prisoner “without any human rights” in his book Deaths of Empresses and Consorts (《皇后之死》). Bo saw Moxi as merely a young girl forcibly “sent away like sheep and cattle to the enemy for the sake of the survival of her clan.”

Xuanjiang 宣姜

Xuanjiang was responsible for the instability and demise of the State of Wei (卫国) during the Spring and Autumn period, at least according to Biographies of Exemplary Women.

Xuanjiang was a concubine to Duke Xuan of Wei, and is supposed to have plotted the death of Xuan’s crown prince Ji Ji (姬伋) so that one of her own two sons could take the throne.

But in the messy assassination attempt, the assassin killed one of Xuanjiang’s sons, while Ji Ji was also killed pursuing the culprit. Duke Xuan died of grief after the crown prince’s death, and Xuanjiang’s second son Ji Shuo (姬朔) took power.

The turmoil didn’t end there for Xuanjiang. Ji Shuo was overthrown, before returning with his uncle to take back the throne. In order to appease his opponents, however, Xuanjiang’s brother forced her to marry the dead Ji Ji’s younger brother.

This was viewed as a disgraceful turn of events for centuries, with Xuanjiang labeled promiscuous and worse for remarrying after the death of Duke Xuan. The Commentary on Poetry (《毛诗序》), a commentary on poems written around 200 BCE, records that the people of Wei regarded Xuanjiang as an animal or worse. Xuanjiang’s name even became a byword to insult women, with even modern analyses of the period labeling her a slut.

What these commentaries continue to overlook, however, is that it was customary for widows to marry their deceased husband’s sons or brothers in this period, not to mention that Xuanjiang probably had little choice in the matter.

In a 1994 paper titled “A Woman Treated Unjustly for Over Two Thousand Years,” scholar Gong Xinggen of Jiangxi’s Yichun University criticized these commentators for using the anachronistic moral standard that widows should stay chaste and never remarry to judge a common practice in the Wei court.

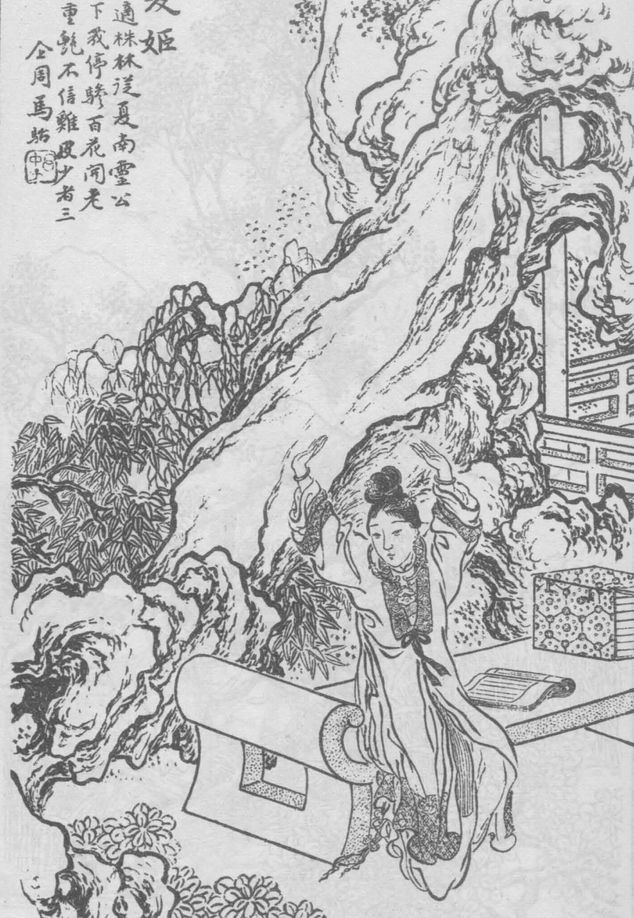

Xiaji 夏姬

Lady Xiaji is frequently described as a perilous woman who brought danger to the men she had relationships with and even caused the collapse of the State of Chen in the Spring and Autumn period. The Commentary of Zuo records that Xiaji had sexual relationships simultaneously with Lord Ling of Chen and two of his associates. The men even fooled around at court by wearing Xiaji’s underwear, according to the text.

Then, in 598 BCE, Xiaji’s son Xia Zhengshu (夏徵舒) murdered Lord Ling after the lord, drunk, had teased him about who his father was. Xia Zhengshu declared himself the new ruler of the Chen state, but quickly faced attack from the neighboring Chu kingdom.

Xia Zhengshu lost, and the Chu king quickly fell for Xiaji’s beauty. He was, however, warned against giving in to his lust and taking her as a concubine by his minister Wuchen (巫臣), who said she was a cursed woman who brought bad luck to men associated with her.

The king sent her far away to marry a widower nobleman, but within just a few days Xiaji’s new husband had died in battle—the nobleman’s son promptly married Xiaji even before his father’s dead body had returned home. But seemingly out of nowhere, minister Wuchen swooped in to elope with Xiaoji to the State of Jin, after he had resigned from his position under the King of Chu.

According to these records, Xiaji married at least four times throughout her life, while Biographies of Exemplary Women labeled her responsible for ruining at least two states as well as causing the death or decline of her male partners.

Scholar Olivia Milburn, however, noted in her 2017 essay on the portrayal of Xiaji that she was far from a bad omen. Rather, she was a victim of powerful men, her fate determined by her beauty and their greed.

Though writing more generally, Lu Xun, one of China’s most famous writers of the 20th century, expressed similar sentiments back in the 1930s. “I think in male-dominated societies, women don’t have such power,” he wrote in his essay Ah Jin (《阿金》). He also hinted that nearly all these records throughout China’s imperial history were written by men, for men. “Male writers always attribute the demise of the country to women. Worthless, useless men!”