Why even TV shows set in the 1990s lean into aesthetics from nearly a century earlier

How much is a night’s stay at a hotel nearly a century old worth? At the Peace Hotel, newly trendy after featuring in renowned director Wong Kar-wai’s hit TV drama Blossoms Shanghai, the answer is as high as 18,888 yuan.

The hotel, a landmark that opened its doors in the heart of Shanghai in 1929, rode a wave of fandom and nostalgia from millions of viewers who were captivated by Wong’s portrayal of the 1990s in China’s financial capital. The hotel has gone viral because Wong’s drama clings to an “Old Shanghai” aesthetic from the 1920s and ’30s, despite being set 60 years later than that.

Colonial-era architecture and mixing cultures remain key parts of many works set in Shanghai. Despite the passage of time and the city’s rapid development into a global financial center, the aesthetic of Old Shanghai still captivates people through film, TV, and literature.

This version of Shanghai stems from the city during the late 19th and early 20th centuries under Qing and then Republican rule. During that time, imperial foreign powers controlled concessions in the city where their citizens enjoyed immunity from China’s laws. Over a century on, parts of Shanghai, notably the riverside Bund and French concession areas, maintained the architectural marks of European colonialism. The era also bequeathed the city a unique fusion of cultures, shaping the city into an amalgamation of Chinese and Western influences that continues today.

The city’s status as a site of foreign aggression but also a bustling symbol of surging modernity and cultural mixing has captured the imagination of Chinese writers and filmmakers ever since. Even as early as 1892, Han Bingqing’s novel The Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai, written in Wu dialect, explored the connection between courtesan culture and a burgeoning modern city in the setting of the concessions. More critically, in the 1930s, Mao Dun’s novel Midnight portrayed the impact of colonialism and capitalism on the city and highlighted the rise of industrialists and the oppression of rural laborers.

Eileen Chang perhaps did the most to cement the idea of Shanghai as a prosperous modernizing cosmopolitan melting pot with a huge wealth gap during a period marked by conflict and turmoil, an image that came to dominate screens and pages in later years. Chang translated Han Bingqing’s novel into Mandarin Chinese and English, and she then wrote some of her most famous works against the backdrop of 1940s upper-class Shanghai life.

Love in a Fallen City and The Golden Cangue explored the lives of wealthy or middle-class women torn between traditional family values and emerging modern concepts during the uncertainties of wartime. Chang’s Lust, Caution, a novella written in 1979 but set in Japanese-occupied Shanghai in 1942, became an award-winning box office hit in 2007 when Ang Lee adapted it into a film.

Chang’s influence on subsequent writers’ portrayal of Shanghai is obvious. Later authors like Wang Anyi also wrote about 1940s Shanghai, despite being born decades later. Wang’s most renowned novel, The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, tells the story of a young Shanghainese girl from the 1940s till her death in the 1970s. Some of their work seemed to reflect a city and atmosphere that no longer existed in the wake of the Japanese invasion and later when the Chinese Communist Party came to power.

Chang and subsequent writers’ works on this period of Shanghai remain extraordinarily popular. “Chang’s Love in a Fallen City features characters struggling with the complexities of relationships during that time, and a sense of identity must be pieced together and then understood in a changing world. I think audiences today can empathize with those feelings as our own world is changing rapidly,” says Ryan Thorpe, a writing and literature professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

He also believes the depiction of drama, revolutionaries, enterprise, crime, and war in many works of literature and film set in Shanghai still captivate people today. “There were gangs and casinos, invading armies and conflicting nations. It was this wild world where outlaws and rogues were more common, and traditional rules were being broken and replaced with something new,” Thorpe tells TWOC.

While other cities in China had similar foreign concessions, Shanghai had the largest, and as a conveniently located port, it became a hub of business and trade too. Xie Qingyu, a writer and literature lecturer based in Changsha, Hunan province, explains that many writers also moved to Shanghai during wartime in the 1930s and ’40s, as they believed the presence of foreign concessions there would make a Japanese invasion unlikely or, after that proved false, Japanese occupation less barbaric.

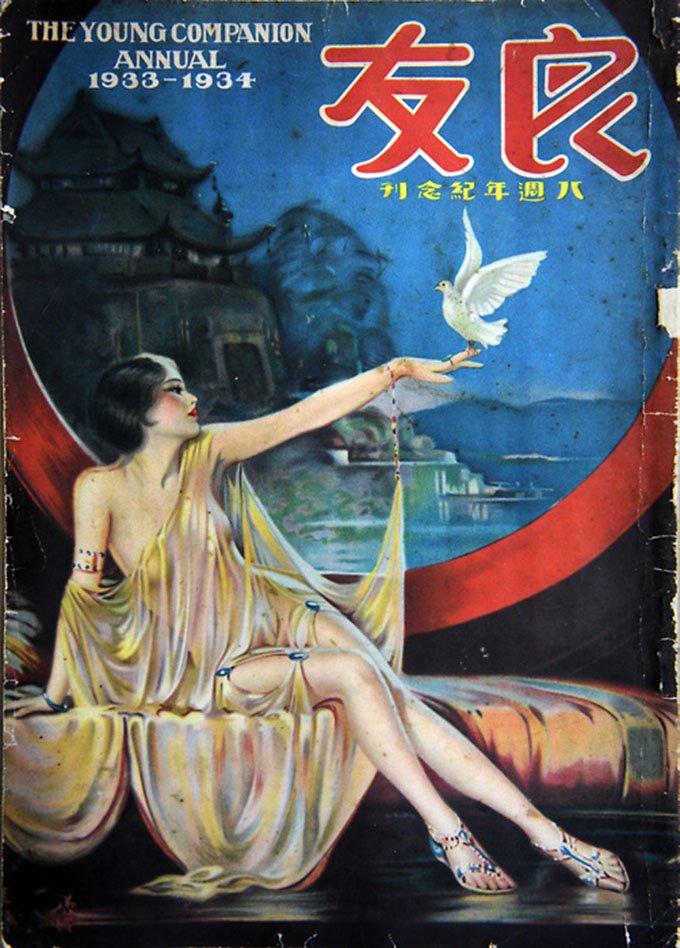

“Throughout the Republican era, Shanghai held a dual distinction as not just an economic powerhouse but also as a cultural center,” says Xie. Influential writers like Lu Xun moved to the city, while major political magazines, such as La Jeunesse and The Young Companion, also based their operations there.

Not everyone was happy about the new trend for writing (or lifestyles) that blended Western and Chinese culture. The term haipai (海派) became an insult hurled at Shanghai writers and artists deemed to have betrayed their cultural roots by indulging in Western cultural tropes or reveling in the cosmopolitanism and flamboyance of Shanghai. But as China began to embrace market reforms in the 1980s, haipai has come to symbolize the modern essence of an open, diverse, and inclusive Shanghai culture.

Despite the rapid development of the skyline in Shanghai’s Pudong district (once an empty river bank but now the site of gleaming skyscrapers, one of them the second tallest building in the world) in the 1990s and 2000s, the now dwarfed Bund on the opposite side of the river remains the center of artistic attention.

The rows of colonial-style buildings—former banks, hotels, and trading administrations for imperial powers—are the backdrop for many iconic works. The Bund, an acclaimed Hong Kong TV drama from 1980, revolves around entrepreneurs and tycoons active around the waterfront location in the 1930s. Sometimes referred to as “The Godfather of the East,” the show displayed a Shanghai racked by gang conflicts and crime.

Shanghai’s importance during the era of conflict with Japan also made it a prime setting for war and espionage works. The 1958 film The Eternal Wave shows Shanghai as a perilous, corrupt place where underground communist agents faced threats from both the Japanese army and traitors within the Republic of China’s rulers, the Kuomintang.

Over 50 years later, Hidden Blade, told a similar story about undercover agents plotting against the Japanese invaders. Released during the Lunar New Year holiday in 2023, the movie made over 900 million yuan at the box office.

Even in works not set in Old Shanghai, the tropes of that era shine through. Blossoms Shanghai still features the iconic Bund in countless scenes, characters climb a colonial-era church for views over the city, and even the sharp, three-piece suits many of the characters wear seem straight out of Eileen Chang’s time.

“It looks more like the exquisite old Shanghai in the ’30s and ’40s,” says Claire Huang, a Shanghai native born in 1986. Huang, a fan of the show, says the fashion in Wong’s drama (with tight-fitting suits and dresses), reflects Old Shanghai, not the 1990s when loose-fitting styles were in vogue. “Wong is really smart to combine people’s memories of the ‘90s and their imagination of Old Shanghai in the Republican era,” she says.

There are some more diverse portrayals of Shanghai these days, but none of them have gained the mainstream popularity of Chang or Blossoms. Xie points to Shanghainese writer Zhang Yiwei’s exploration of ordinary women and family life in Shanghai. Zhang, born in Shanghai in 1987, has written about life in “new villages for workers,” public housing built during the 1950s for model workers in the socialist economy. These low-rise apartment buildings that Zhang grew up in during the 1990s, long after high-rise apartment buildings went up, are a far cry from the glitz and opulence of the Bund. Zhang’s work “possesses an authentic, lifelike quality that deeply resonates with me,” Xie says.

Despite that, Xie admits that much of her own writing focuses on Old Shanghai. One of her novels, heavily influenced by Eileen Chang, is about a courtesan living on the Bund in the Republican era. Old Shanghai nostalgia will probably dominate artistic portrayals of the city for a long time to come.

Contributions from Sam Davies and Hayley Zhao