Discover these ancient Chinese “chengyu” still used to identify modern misinformation

In April, Chinese influencer Xu Jiayi, better known by her online handle “Thurman Maoyibei,” learned a hard lesson about spreading fake news online when her social media accounts were suspended.

During the Lunar New Year holiday, Xu, who has almost 40 million followers across social media platforms, posted a video claiming she had found a Chinese elementary student’s winter vacation homework in a Paris restaurant’s bathroom. She called on her followers to help find the owner. Many people, perhaps hoping to ensure the child couldn’t escape their holiday assignments, joined the search for the student.

The video gained 5 million likes in days before it was exposed as a hoax orchestrated by Xu and her agency. Xu now faces administrative penalties and the incident is listed as one of 10 representative misinformation cases by China’s Ministry of Public Security. On April 23, following Xu’s downfall, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced a two-month nationwide crackdown on fraudulent content aimed at “attracting traffic” on social media.

Yet as several idioms with ancient routes suggest, China’s fight against rumors dates back thousands of years. Some of these chengyu are still in use today. Learn how to use them to talk about fake news like a local:

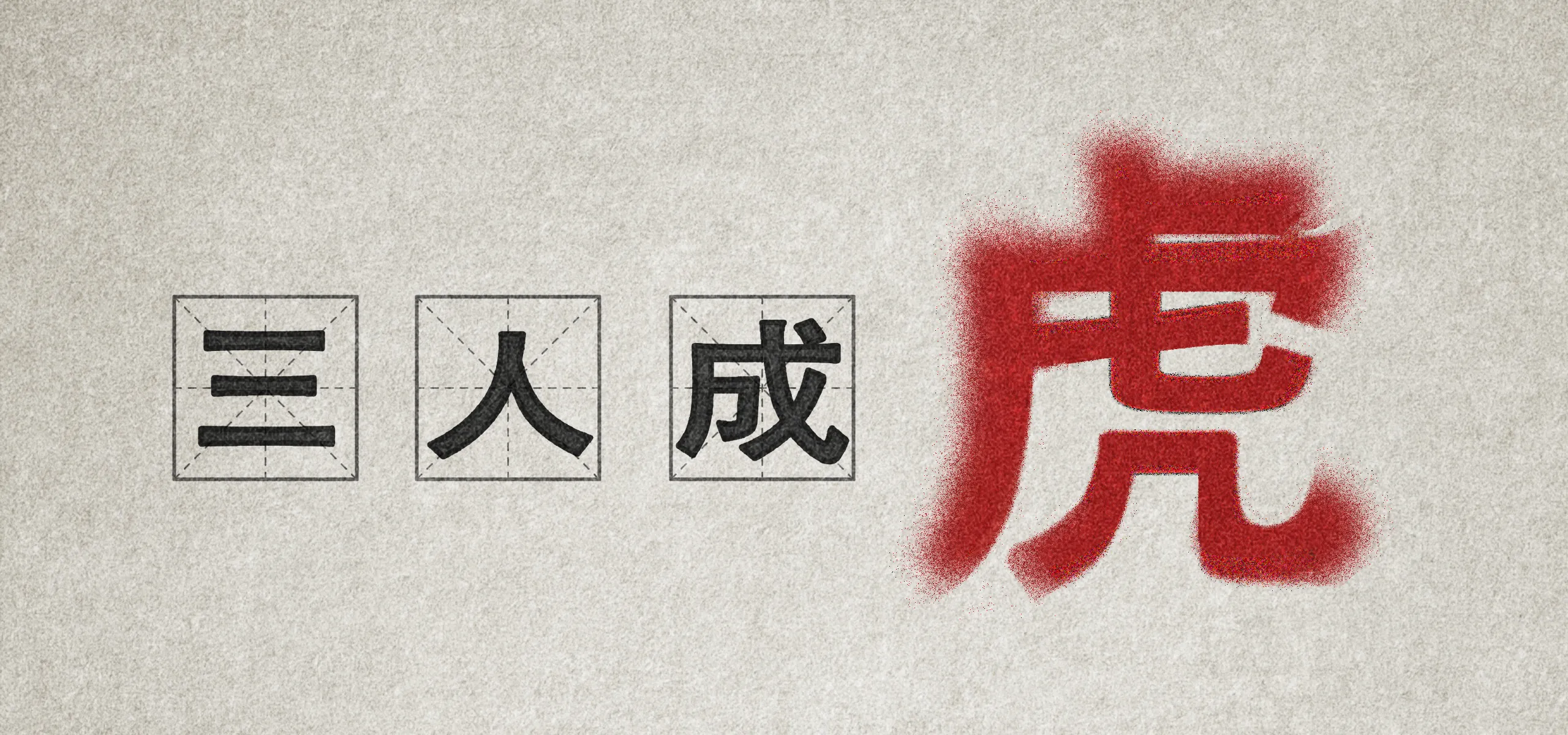

Three people make a tiger 三人成虎

According to the Strategies of the Warring States (《战国策》), a text on diplomacy and strategies compiled during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), Pang Gong (庞恭), a chancellor of the State of Wei was sent as a hostage to the State of Zhao. Before he left, Pang talked to the King of Wei, cautioning him against potential future rumors of Pang’s betrayal that Pang felt sure would circulate once he was gone:

“If one says they saw a tiger in the streets, would you believe it?” Pang asked the king.

“No,” the king responded.

“What if a second person claims the same?” Pang inquired.

“Still skeptical,” the king said.

“And if a third person asserts it?”

“Then I’d believe it’s true,” the king answered.

Pang clarified his point: “Even unlikely events, like a tiger sighting on the street, can become believable with enough claimants. Given my long journey to the State of Zhao, should more than three people speak ill of me, I hope your honor can still discern the truth.”

Despite Pang’s warning, the king believed rumors of his disloyalty in his absence. When Pang returned from the State of Zhao, the king never called him to court again. Pang’s warning coined the idiom “three people make a tiger.” The phrase is still commonly used today to describe how repeated lies can become accepted truths.

Last October, for example, a false news report of an explosion at a factory in Jiangsu province began spreading online. A police investigation found that the video purporting to show the deadly explosion was AI-generated. Three suspects were arrested and accused of creating the clip to drive traffic to their social media accounts. This incident shows that:

Even in modern society, “three people make a tiger” stories still frequently occur.

即使在现代社会,三人成虎的故事依然经常出现。

Zeng Shen killed a man 曾参杀人

A similar story happened to Zeng Shen (曾参), a renowned scholar from the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) and one of Confucius’s most famous students. According to the Strategies, a man with the same name committed murder, and someone went to tell Zeng’s mother that her son was the culprit. Initially, she dismissed the news and continued weaving as if nothing happened. After a while, another person came and said “Zeng Shen has killed a man.” But she remained composed. She finally believed it only after a third person delivered the same report. Panicked, she threw down her shuttle, climbed a wall, and ran away.

The story then was distilled into the chengyu “Zeng Shen killed a man,” demonstrating that even the most trustworthy can be undermined by persistent rumors.

In 2020, a woman in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, suffered from false rumors online. First, she was secretly filmed picking up a package in her residential compound. Then, the clip was posted to the compound’s resident WeChat group along with fake screenshots of intimate and sexual messages, suggesting the woman was cheating on her boyfriend with a delivery person. The messages spread in her compound and eventually reached her work colleagues. The woman’s company forced her to resign, claiming the incident negatively impacted the firm’s reputation.

The victim eventually won a defamation case against the slanderers, who were jailed. But the damage to the woman’s life had already been done.

The spread of these rumors is like “Zeng Shen killed a man”—Those close to the situation initially don’t believe it’s true, but their conviction wavers once many people start repeating the rumors.

这些谣言就像“曾参杀人”,虽然最开始并无杀伤力,但因为说的人多了,身边人也开始发生动摇。

A shortcut in Zhongnan Mountain 终南捷径

Misinformation is not only employed to undermine others, it can also be an effective tool for self-promotion. Lu Cangyong (卢藏用), a scholar during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), mastered this strategy, ultimately securing a major promotion.

According to New Anecdotes of the Tang Dynasty (《大唐新语》), Lu was a talented man who received little recognition for his work in the government. Lu decided to become a hermit, a group revered for their profound learning and wisdom. He hid in Zhongnan Mountain near the capital Chang’an while spreading the word about his commitment to a life of seclusion.

Lu’s reputation soon soared, and later the court summoned and promoted him. However, some saw through his ruse. Years later, when Lu met Sima Chengzhen (司马承祯), a genuine Daoist hermit from Zhongnan Mountain, Lu gushed about the beautiful scenery on the mountainside. Sima, in turn, quipped that the best thing about the mountain was that it contained a shortcut to a successful career. Sima’s barb birthed this pejorative chengyu: “A shortcut in Zhongnan mountain.” It’s used to refer to using despicable or underhand means to seek fame or fortune.

For example, the Xu Jiayi case shows that:

Fabricated short videos have become the new “shortcut in Zhongnan Mountain” to gain traffic and exposure online.

“自导自演”式的短视频,已经成为互联网时代下获得流量曝光的新终南捷径。