Chinese migrants helped shape Milan’s Sarpi–Canonica district for a century, but soaring rents, shifting urban planning, and cultural tensions are now eroding the enclave’s diaspora-driven character. A new generation of Italian-Chinese entrepreneurs may determine whether it endures.

A subtle yet striking transformation emerges as one moves north along Via Bramante in Milan’s central Sarpi-Canonica district. The basil-and-tomato aroma of streetside meals slowly gives way to more peppery spices. Middle-aged men jostling trolleys stacked with products labeled “Made in China” have become a common sight. Shop signs hanging above graffiti-covered walls increasingly feature the characters “贸易,” or trade. And Mandarin starts to dominate street chatter.

But aside from these few telltale signs, the area shows little of what one would expect from one of Europe’s oldest enclaves for Chinese immigrants and businesses. Home to over 4,000 ethnic Chinese, the area feels mostly like your standard European retail business district; there is no paifang, or traditional Chinese gate—a staple of Chinatowns worldwide—instead, visitors are welcomed by an iconic “I Miss You in Milan” blue street sign in front of popular Chinese milk tea brand ChaPanda.

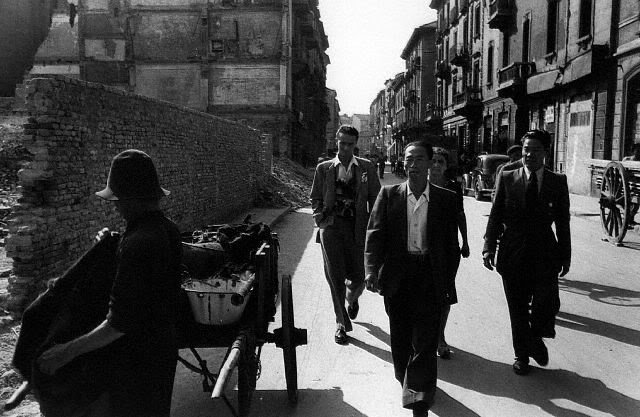

The lively, fast-modernizing neighborhood in Milan’s northwest looks nothing like it did before World War II. A wave of changes has further reshaped the area’s identity. Now, a century after the first Chinese migrants arrived, residents are increasingly being priced out, leaving the future of Milan’s Chinatown hanging in the balance.

The makings of home

The window display of the Oriente Store, an antique shop at the corner of Via Bramante and Via Paolo Sarpi, showcases a range of Chinese trinkets, from Buddhist statues and porcelain to traditional Chinese attire. It’s nearly 7 o’clock, and the store is about to close when an older woman hurries out from the back to balance the cash register. When asked where she’s from, she replies, “Wenzhou, Zhejiang, like many in this community.”

Read more about Chinese diasporas:

- Qingtian: China’s “Little Europe” with a County-Town Heart

- Souls Left Behind: The Forgotten Chinese Heroes in WWI

- Haven of Humor: How Chinese Migrants in Europe Find Comfort in Comedy

Among the first Chinese immigrants to arrive in Italy were men who were employed by Britain and France to fill critical labor shortages, digging trenches, repairing infrastructure, and making munitions across Europe during World War I. After the war, rather than returning to China, they sought new opportunities where they could. Some began trickling south, making their way to Italy, first landing in Turin, and later selling imitation pearls on the streets of Milan.

By the early 1920s, new immigrants began arriving from China. Most, like the shopkeeper, were from Zhejiang province’s coastal Wenzhou city and nearby counties like Wencheng and Qingtian. Many of the first Wenzhounese migrants were skilled agricultural workers and stonemasons.

“They chose an area called Borgo degli Ortolani because of its proximity to a train station, low rent, and facilities for manufacturing workshops,” Zhang Gaoheng, associate professor of Italian studies at the University of British Columbia, tells TWOC.

Situated near Milan’s historical center, Borgo degli Ortolani, or “the village of gardeners,” was once a low-income neighborhood. According to Patrizia Battilani, a Chinese migration researcher at the University of Bologna, there were 175 Chinese people residing in the area in 1936, forming the “first real Chinese community in Italy.” By the 1940s, Chinese immigrants had become the largest minority group in the area and in neighboring Canonica Sarpi. More arrivals followed in the 1950s and 60s, but the true wave of migration from the Chinese mainland began in the 1980s after China’s reform and opening up, and “Italy’s unsystematic immigration policy enabled many undocumented migrants to enter,” Zhang says.

Over time, Milan’s Chinese community shifted into producing and selling silk, leather goods, and other apparel-related services. Borgo degli Ortolani also gradually developed into an industrial district, attracting craftsmen of various trades.

Today, around 300,000 Chinese live in Italy, with Milan’s Chinese population hovering at 40,000. According to government data, nearly 13 percent of Milan’s retail companies are owned by residents born in China.

A Chinatown in flux

Like in many immigrant communities, the path to settling in Italy came with hurdles. In the 1990s, as more newcomers arrived, larger office spaces appeared, and the area’s cultural fabric began to shift.

“Before the 2000s, things were good, as locals perceived the Chinese as underdogs. Their numbers were relatively low, and imports from China benefited [the locals],” says Zhang.

But as the narrow cobblestone street of Via Paolo Sarpi, named after the 16th-century Venetian polymath, became clogged with trucks unloading merchandise, resentment grew among local Italians over traffic, the growth of Chinese wholesalers, and the neighborhood’s rapid transformation.

A riot even broke out between the two communities in 2007 after a Chinese woman received a 40-euro parking ticket while unloading shoes. Frustrated by repeated fines and inspections, over 300 Chinese residents confronted baton-wielding police, sparking a small riot and a debate over whether the community was being unfairly targeted. At least 25 police officers and more than a dozen protesters were injured.

After the 2007 protests, the neighborhood continued to face a series of challenges of what came to be called the “Sarpi question.” Milan city officials had to balance the demand from local residents for a stronger “Italian flavor” with the Chinese community, which had built a wholesale-focused economic hub in the area. Over several years, discussions with local Chinese business groups led to gradual traffic restrictions, and by the early 2010s, most Chinese wholesalers had moved to Milan’s outer districts, many settling in the logistical hub of Lachiariella. Looking to prevent future issues, the local Milanese government redesigned Via Paolo Sarpi’s once-narrow paths into wider, retail-focused pedestrian streets lined with flower beds.

But that doesn’t mean that all Chinese immigrants are leaving the area. “More [Chinese] retailers began to operate in the area. Besides, older Italian proprietors needed to sell, and the Chinese bought,” says Zhang. “Visually speaking, Milan’s Chinatown, compared to London’s, feels very modern...Via Sarpi and the surrounding area has a very high concentration of Chinese-managed businesses that I didn’t find in Paris’s Belleville [Chinatown].”

Now, instead of the dense markets and lantern-lined streets typical of traditional Chinatowns, the area is known as a trendy, chic spot defined by boutique shops, Chinese grocery stores, and fusion restaurants, opened by the new generation of Chinese or Chinese-Italian entrepreneurs.

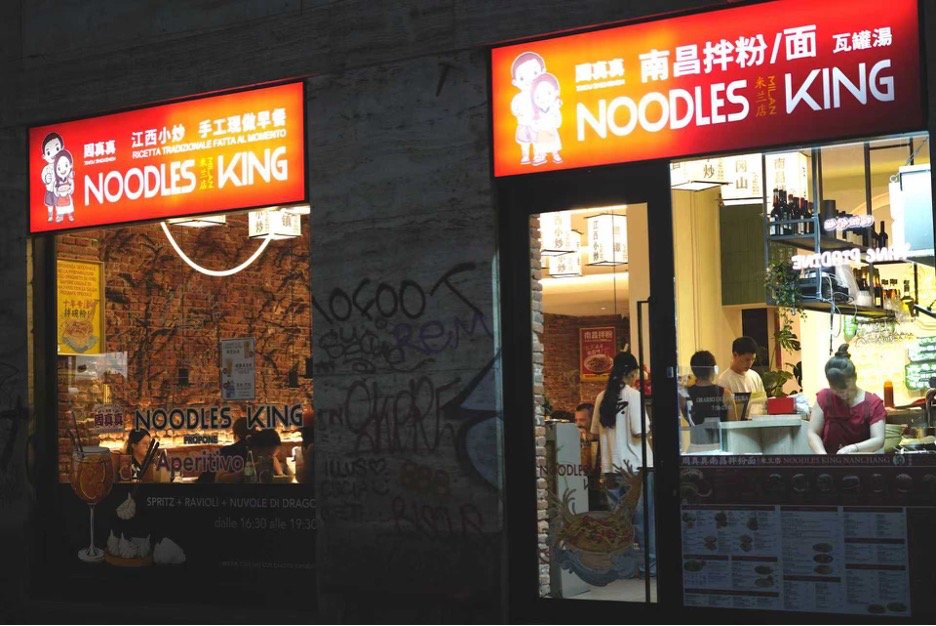

“The first generations used to work and think in a very conservative way. Now these new young entrepreneurs, [aged] between 30 and 40, have a new business vision,” says Sarah Manganotti, vice president of Associna, a Milan-based non-profit founded by second-generation Chinese-Italians. “We used to have electronic repairs and mobile phone shops. Then there was a wave of beauty, massage, nails, and fast fashion. Now this new trend is pretty much fast food, and it’s become a huge part of Chinatown.”

Even street art lining the bustling street has more modern twists, like the black-and-red mural of last year’s viral game Black Myth’s Sun Wukong.

“Chinatown in Milan is becoming like Little Italy in Lower Manhattan in New York City. They are products and expressions of a neoliberal leisure lifestyle that cosmopolitans, or at least big city residents, are urged to adopt,” says Zhang.

Priced out

As the neighborhood modernizes and gentrifies, more of Milan Chinatown’s old residents are moving out. “Currently, about 10 percent of Chinese and Chinese Italians live there, but many are settling throughout the city,” says Battilani.

Rental prices have skyrocketed around Via Paolo Sarpi, tripling to over 4,000 euros per square meter. “It has become an area for the rich,” says Manganotti.

It’s not just Milan. Gentrification and high-end development have altered the social and spatial fabric of Chinatowns worldwide, which have traditionally been hubs of entrepreneurship and cultural landmarks. Many now rely heavily on tourism to stay afloat. In Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, new stadiums have disrupted Chinatown neighborhoods, while New York’s Manhattan Chinatown faces the construction of a 300-foot-tall detention center that threatens local businesses and cultural identity.

While Milan’s Chinatown still retains its Chinese roots, it is now shaped more by contemporary urban trends from the Chinese mainland, and only those with enough capital, like chain stores Coco, Juewei Duck Neck, and Yuanji Dumplings, can afford to open shops here.

“Today, Milan’s Chinatown is neither a predominantly Chinese residential area, nor a tourist district,” Nicola Montagna writes in his research about the contestation of space in Milan’s Chinatown. “Rather, it is an ethnic economic and commercial enclave in a gentrified area near the city center, where businesses owned by Italians and foreign nationals coexist.”

Forming a new identity

“The Chinese community took shape in Milan a century ago. Its history should be told and preserved as part of the Milan heritage,” says Battilani.

While the old Chinatown may be hard to recognize today, Chinese culture continues to weave itself into local Italian life. In 2024, Via Paolo Sarpi became a hotspot during Milan Design Week, featuring Chinese artists exploring the cultural and historical ties between the two countries. In March 2025, the city celebrated 100 years since the first Chinese arrived in Milan. From second-generation Chinese finding success with creative Chinese-Italian cuisine to a Milanese square becoming the first in Italy dedicated to a Chinese individual, the relationship between the two cultures appears to be moving in a positive direction.

Every evening, amid the noise and neon of Via Paolo Sarpi, Chinese cooks bustle over boiling dumplings while the sizzle of Nanchang-style noodles being prepped for delivery fills the air. In dimly lit bars, Chinese patrons laugh and drink away the day. Italians, Indians, Chinese, and other nationalities intermingled, munching on the plethora of Chinese cuisine available at every corner. The lively streets seem to suggest that, despite cultural shifts and economic changes, Chinatowns, though ever-changing, can endure and flourish through the ages.

A Century After Its Founding, Milan’s Chinatown Faces an Uncertain Future is a story from our issue, “New Markets, Young Makers.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.