How the character for “harvest” came to symbolize gain, profit, and advantage

It is human nature to pursue what benefits oneself, Chinese philosopher Xunzi (荀子) points out over 2,000 years ago. Sima Qian (司马迁), a historian from the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), agrees. In the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), he writes, “The world hustles for nothing but benefit; the world bustles for nothing but interest (天下熙熙,皆为利来;天下攘攘,皆为利往 tiānxià xīxī, jiē wèi lì lái; tiānxià rǎngrǎng, jiē wèi lì wǎng).”

While Xunzi viewed self-interest as proof that human nature is evil, Sima Qian takes a more neutral stance, believing that self-serving pursuits are essential to economic and social development. As a pioneering advocate of commerce, he recorded many accounts of successful businesspeople dating back to the sixth century BCE, including Zigong (子贡), a noted disciple of Confucius. He argued that the best rulers support people’s natural economic activities and grant them the necessary freedom. The next best approaches, in descending order, are to “guide them through incentives (利道之 lì dǎo zhī),” to educate them, and to restrain them with regulations. The worst of all is to compete with them—a critique of government business monopolies.

Learn more Chinese characters:

- 构: The Character That Brings Blueprints Into Reality

- 爱: The Character Defining Love in Its Many Forms

- 文: A Character That Once Referred to Barbarians Now Represents Civility

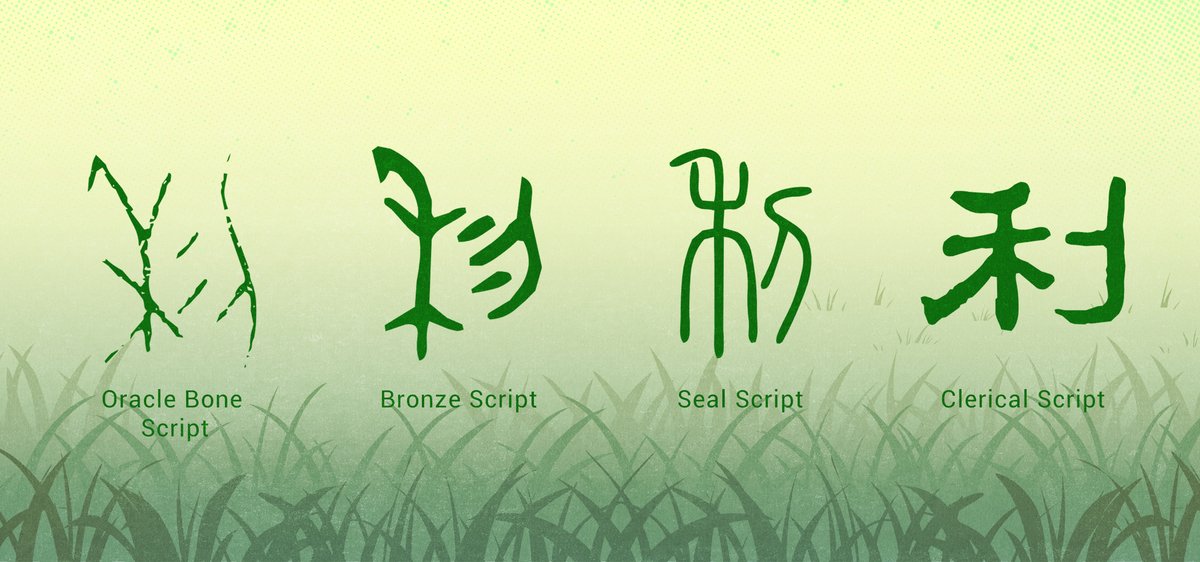

Benefits are abstract, but the character 利 (lì) is specific in its origin. Over 3,000 years ago, its earliest form appeared in oracle bone script, which consists of a 禾 (hé, crop) radical on the left and a 刀 (dāo, knife) radical on the right, with several grains depicted around them. Scholars interpret its original meaning as “to harvest crops.” Later, 利 came to signify “gain” in a broader sense, forming modern terms such as 利益 (lìyì, interest). We can speak of individual interests (个人利益 gèrén lìyì), collective interests (集体利益 jítǐ lìyì), and national interests (国家利益 guójiā lìyì).

An alternative interpretation of the oracle bone script for 利 sees it as representing a sharp harvesting tool, which is equally plausible, given that the character also carries the meaning of “sharp” in modern Chinese. It commonly appears in the word 锋利 (fēnglì, sharp), and is used in both literal and metaphoric senses. A sharp knife is 利刃 (lìrèn), a sharp sword is 利剑 (lìjiàn), while a sharp tongue is 利口 (lìkǒu, literally “sharp mouth”) or 利齿 (lìchǐ, “sharp teeth”). Then there’s 犀利 (xīlì), meaning “keen” or “incisive,” for instance: 她的目光很犀利,仿佛能看穿别人的心思 (Tā de mùguāng hěn xīlì, fǎngfú néng kànchuān biérén de xīnsi. Her eyes are sharp, almost as if they can read other people’s minds).

In traditional Chinese society, influenced by Confucianism, moral and social duties are often prioritized over self-interest. As Confucius said: “The virtuous are motivated by justice, the selfish by personal gain (君子喻于义,小人喻于利 jūnzǐ yù yú yì, xiǎorén yù yú lì).” This idea is summed up in the idiom 重义轻利 (zhòngyì qīnglì), which means “putting morality above personal gain.” As a result, many expressions containing the character 利 take on a negative tone, such as 唯利是图 (wéilìshìtú, seek nothing but profit) and 利欲熏心 (lìyù xūnxīn, blinded by greed).

The legal term 权利 (quánlì), or “right,” did not emerge until the mid-19th century. Before then, it meant “power and gain” and often carried a negative connotation. In 1864, American missionary William Alexander Parsons Martin repurposed the term in his Chinese translation of Elements of International Law by Henry Wheaton, using it to denote legal rights—a meaning that has remained ever since. Another modern legal term built on 利 is 专利 (zhuānlì), or “patent.”

The character 利 is often paired with its antonym 害 (hài, harm or evil) to contrast the pros and cons of a subject, as in 利害得失 (lìhài déshī, advantages and disadvantages). You may describe something beneficial as 有百利而无一害 (yǒu bǎi lì ér wú yí hài, doing all good and no harm), and denounce something harmful as 有百害而无一利 (yǒu bǎi hài ér wú yí lì, doing all harm and no good). For instance, teachers may say: “过度沉迷网络游戏对青少年的成长有百害而无一利 (Guòdù chénmí wǎngluò yóuxì duì qīngshàonián de chéngzhǎng yǒu bǎi hài ér wú yí lì. Online gaming addiction does all harm and no good to teenagers’ growth).”

This character is also seen in verbs. 利己 (lìjǐ) is to act for one’s own benefit, while 利他 (lìtā) is to benefit others. Those who only care about themselves are termed as 利己主义 (lìjǐ zhǔyì, egocentrism). Even worse is when a person ends up disadvantaging themselves in the process of harming others, or 损人不利己 (sǔnrén bú lìjǐ). Adjectives using 利 typically describe things that go well, as in 顺利 (shùnlì, smooth), 便利 (biànlì, convenient), and 吉利 (jílì, auspicious). If one starts something off on the wrong foot, it’s 出师不利 (chūshī bú lì).

In modern times, 利 is often seen in the economic and financial sectors, where it indicates monetary gains. The interest one gets from a payment or deposit is 利息 (lìxī), and a business profit is called 利润 (lìrùn). The phrase 一本万利 (yìběn wànlì, “one capital, ten thousand profits”) describes a very successful investment, while 暴利 (bàolì), or “exorbitant profit,” denotes profits from illegitimate means.

To sum up, it may be human nature to chase after benefits for oneself, but one must be careful of the means. As the Chinese saying goes, “A virtuous person may seek wealth, but only through proper means (君子爱财,取之有道 jūnzǐ ài cái, qǔ zhī yǒu dào).”

利: The Character That Reaps Everything from Crops to Profits and Wealth is a story from our issue, “New Markets, Young Makers.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.