From your appearance to your inner world, this is the character to mastering every new year

Almost anyone who has tried to lose weight knows the golden rule: Control your mouth and move your legs (or simply, diet and exercise). Sounds easy enough. But a few months into the new year, more and more young Chinese are discovering they cannot rely on willpower alone to sustain healthy habits.

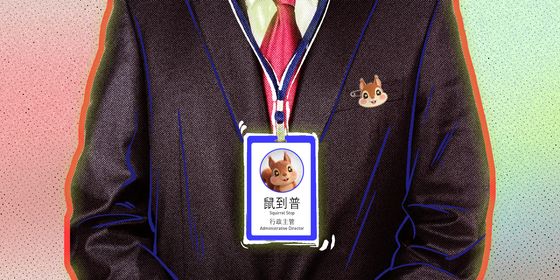

Enter 邪修 (xiéxiū, literally “heretical cultivation”), a term originating from fantasy novels whose protagonists used unorthodox, even immoral means to develop special powers or gain immortality. Now, it has been adopted by young internet users to refer to unusual lifehacks. Some of this year’s heretical weight-loss trends include eating at a snail’s pace, blindfolding oneself during a meal, and, mostly bizarrely of all, referring to oneself as a “dog”—an animal who will get sick from rich foods or sweets, and needs to be walked regularly.

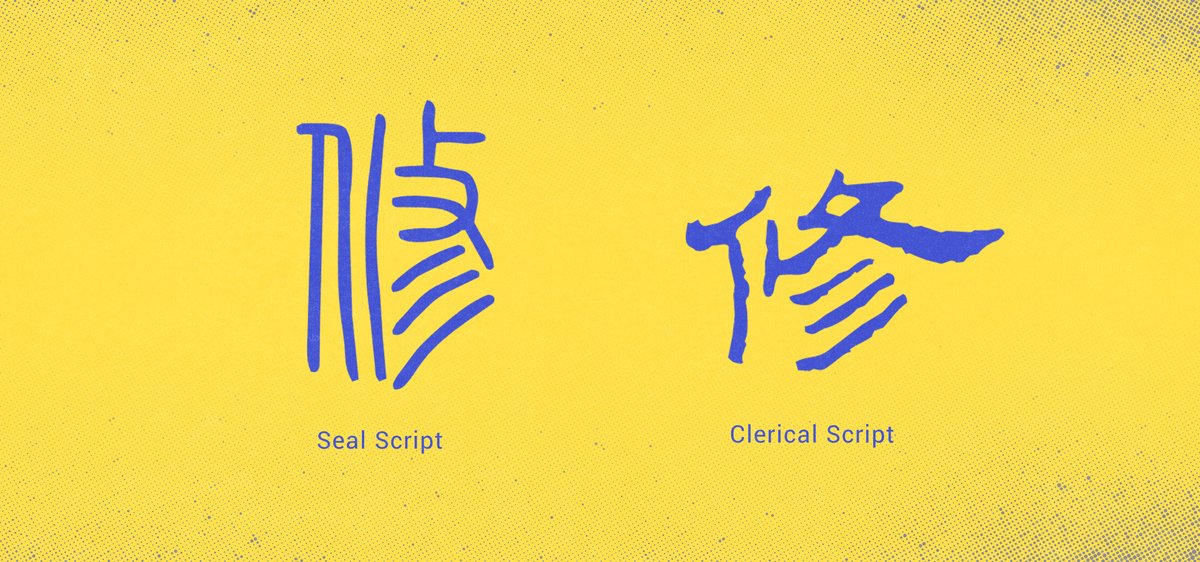

While the practice of 邪修 is considered tongue-in-cheek, the character 修 (xiū) is a serious business. It first appeared in seal script over 3,000 years ago and consisted of a 攸 (yōu, slow and leisurely) radical on the left and top. This provided the original pronunciation, which evolved to be “xiū” later. The 彡 (shān) radical at the bottom-right corner that refers to the sheen of something that has been carefully wiped with a piece of cloth, and clues us to 修’s original meaning: to embellish or adorn.

Learn more Chinese characters:

- 构: The Character That Brings Blueprints Into Reality

- 利: The Character That Reaps Everything from Crops to Profits and Wealth

- 能: A Character Capable of Anything

In his poem “To the Lord of River Xiang (《湘君》),” the third-century BCE scholar Qu Yuan (屈原) uses this meaning of the character to describe how the Lady of River Xiang, a goddess who governs the water, decks herself out to meet her husband (who sadly never shows up): “Fair and duly adorned, I float on rapid stream in my boat of osmanthus wood (美要眇兮宜修,沛吾乘兮桂舟 měi yāo miǎo xī yí xiū, pèi wú chéng xī guìzhōu).”

This goddess from a millennia-old poem seems no different from any modern woman dressing up for a date. In modern Chinese, though, it’s more common to see 修 as part of the phrase 修饰 (xiūshì, to polish, adorn). For instance, the 20th-century playwright Cao Yu portrays one character in Sunrise (《日出》): “她薄薄敷一层粉,几乎没有怎么修饰 (Tā báobáo fū yì céng fěn, jīhū méiyǒu zěnme xiūshì. She is barely made up except for some powder).” Today, people have the option of editing their photos, or 修图 (xiūtú), in addition to themselves.

It’s not only people who can be adorned: 修辞 (xiūcí, “embellishing diction”) is the act of using figures of speech, or 修辞手段 (xiūcí shǒuduàn), in our language. When applied to non-humans, 修 can also mean “to repair.” 修理 (xiūlǐ) refers to the repair of broken machinery or devices. 修理汽车 (xiūlǐ qìchē), or 修车 (xiū chē) for short, is to repair a car, and a mechanic who makes repairs is a 修理工 (xiūlǐgōng). Making regular maintenance checks before a machine breaks is 维修 (wéixiū), literally “maintain and repair.” When old buildings become dilapidated, they require a 翻修 (fānxiū)—a thorough renovation.

修 can also refer to building totally new structures. As the Western saying goes, Rome was not built in a day, and 修筑 (xiūzhù) is the proper phrase to use for the construction of grand projects from scratch. However, while one can speak of 修筑长城 (xiūzhù Chángchéng, building the Great Wall), any non-monumental construction should use the verb 修建 (xiūjiàn), whether it’s a house or a dam. In colloquial speech, people also use 修 as a verb by itself, as in 修铁路 (xiū tiělù), which means building a railway, not fixing one.

Due to its multiple meanings, some of the more abstract uses of 修 can be confusing. 修好 (xiūhǎo) can literally mean “successfully repaired” when applied to objects, but in literary or diplomatic contexts, it can also mean “to foster cordial relations.” For instance, one might hear on the news: 经过多次谈判,两国从此修好 (Jīngguò duō cì tánpàn, liǎng guó cóngcǐ xiūhǎo. The two countries have fostered cordial relations after multiple negotiations). Similarly, in the old days, 修史 (xiū shǐ) refers to writing and compiling historical records, not editing them.

Today’s weight-loss hacks belong to another category of the meanings of 修: “learning.” When professionals undergo training to improve their skills, the verb is 进修 (jìnxiū, further study, advanced education). University courses are usually categorized as 必修 (bìxiū, mandatory) or 选修 (xuǎnxiū, elective), and the self-study classrooms for students are called 自修室 (zìxiūshì). In religious contexts, 修道 (xiū dào) means to cultivate oneself according to a religious doctrine. Catholic monasteries are called 修道院 (xiūdàoyuàn), home to 修士 (xiūshì, friars) and 修女 (xiūnǚ, nuns).

Traditional Chinese culture also emphasizes the cultivation of one’s moral character, or 修身 (xiūshēn). Under Confucian beliefs, this is the first step to governing a state well, as indicated by the classic work “The Great Learning (《大学》)”: 修身齐家治国平天下(xiūshēn qíjiā zhìguó píng tiānxià) or “cultivate oneself, then put the family in order, then govern the state rightly, and bring peace to the world.” However, when one is dedicated to a great cause or career, being slovenly in personal appearance, or 不修边幅 (bùxiū biānfú), is actually considered a virtue, which sounds like a great excuse in a few months’ time when, in spite of 邪修, you find that you still haven’t reached any healthy living goals at all.