How China’s hotels transformed from exclusive spaces for the privileged to accommodation for the masses

In 1979, the Chinese government invited the great German conductor Herbert von Karajan to tour the country. But there was a problem: there weren’t enough hotel rooms in Beijing to accommodate von Karajan and his 200-strong orchestra.

After decades of being closed to foreign tourism, rooms were at a premium. The Ministry of Culture proposed that Karajan and nine other leading members take a room each in the Beijing Hotel, while the other musicians would share rooms at the Qianmen Hotel. The Beijing Hotel resisted. Managers claimed it was inappropriate to give musicians accommodation normally reserved only for visiting heads of state. Just three hours before the orchestra’s arrival, after prolonged negotiations, the hotel allocated the 10 single rooms.

This was not snobbery from the Beijing Hotel. The shortage of hotel rooms in the 1970s was a big problem. According to the Beijing Daily, there were only 11 hotels for international guests with less than 4,000 guest rooms available when von Karajan arrived.

Today the Beijing Hotel is open to everyone who can pay the 800 to 1,000 yuan a standard room typically costs. But in the ’70s, it was one of the most prestigious places to stay in the capital. It operated under the State Council and was mainly reserved for high-level officials from abroad.

Almost all hotels were state-run and reserved for traveling officials then. Guests needed letters from government departments or businesses for a room. It wasn’t until the 1980s that market reforms allowed the private hotel industry to develop and more options to sprout.

The dearth of accommodation options in the 1970s and ’80s was not typical in Chinese history. The Rites of Zhou (《周礼》), a work on the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE) politics and culture, describes inns every 30 li (a Chinese measurement equal to around 500 meters), and markets with accommodation every 50 li on the roads.

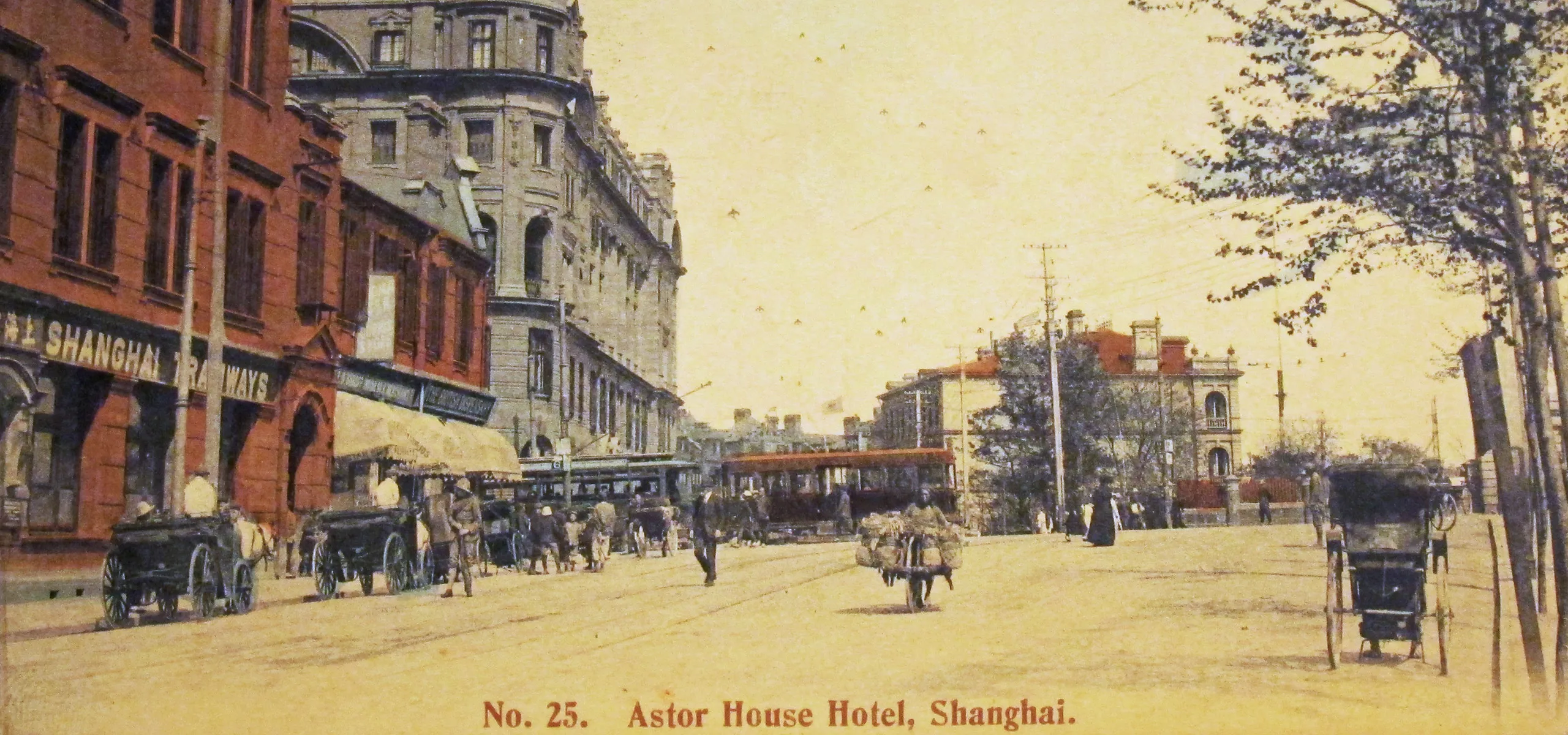

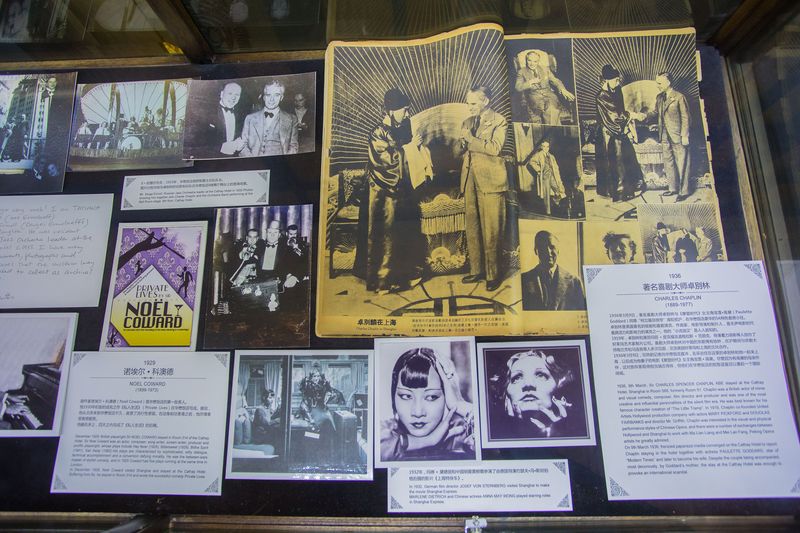

By the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasties, inns and hotels were increasingly common, and in the early 19th century, foreign capital brought Western-style hotels. They mainly served foreign officials and business people in ports opened up to trade after imperial powers imposed unequal treaties on China. They also brought new technologies. The Astor House Hotel in Shanghai featured China’s first electric light, first telephone, and first ballroom. By the 1930s, foreign hotels had spread throughout the foreign concessions in Shanghai, Guangzhou, and elsewhere.

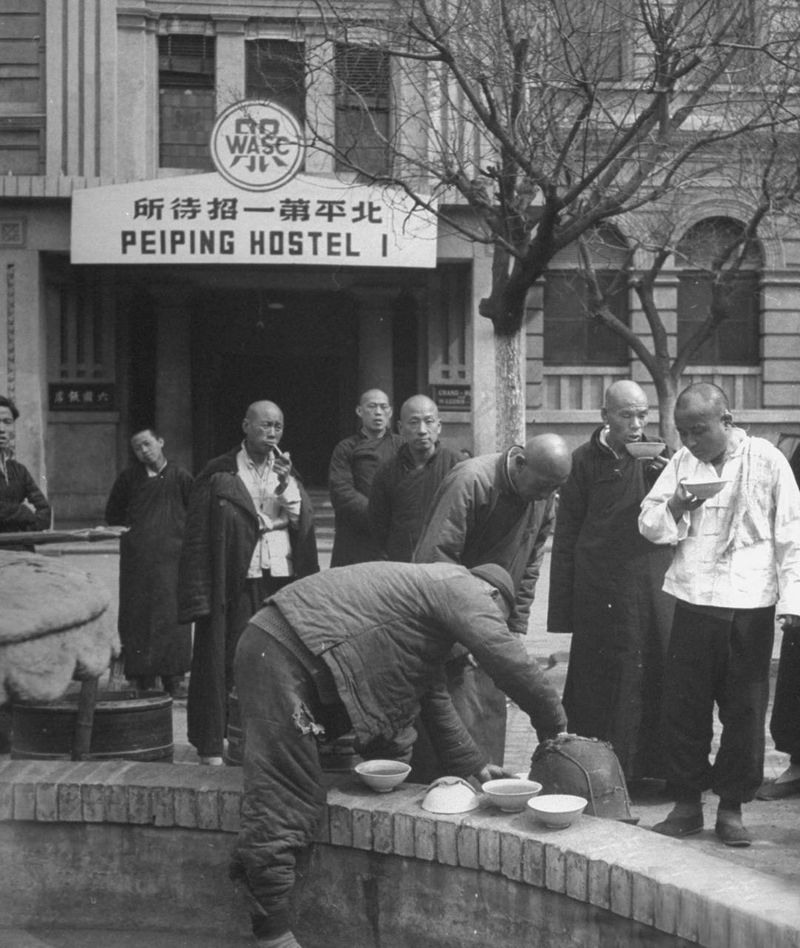

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the state ran hotels and used them mainly to accommodate foreign guests and domestic business travelers. “By 1978, China had 137 hotels with 15,539 rooms. But the vast majority were hostels and state guesthouses,” Zhao Huanyan, a special researcher at the Tourism Research Center of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, told Yicai magazine in 2019.

These hostels, or zhaodaisuo (招待所), were mainly set up by work units to receive traveling employees or officials. Their facilities were often basic. If visitors were lucky, the hostel would provide them with an iron thermos flask of hot water, portable washbasins, plastic slippers, and public washing rooms. Shared rooms were common. State guestrooms, on the other hand, were directly operated by government bureaus and served as reception hotels for Party and state leaders, as well as foreign dignitaries. These were much more luxurious.

Neither hostels nor state guesthouses accepted tourists. Guests needed an official letter issued by their work unit stating their identity, workplace, and purpose of their business trip. In his essay “Shanghai 1981,” Professor Yan Feng from the Chinese Department of Fudan University recorded being rejected by a hostel as a high school student because he and his friends lacked a letter. “The hostel staff said, ‘There’s nothing we can do. Even if you have a letter of introduction, you can’t stay because all the rooms are full,’” Yan wrote. They ended up staying in a public bathhouse overnight, a trend that has returned in recent years as young Chinese tourists attempt to keep their holiday accommodation costs down.

As China’s economy opened up in the late 1970s, tourism surged. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, in 1978, the number of inbound trips to China reached over 1.8 million, exceeding the total of the previous two decades. The next year, this number hit 4.2 million.

Business people struggled to find accommodation even at China’s largest trade fair, the China Import and Export Fair (commonly known as the Canton Fair abroad) in Guangzhou. In 1978, when the press reported the story of a French businessman who couldn’t find a hotel room in Guangzhou for the Fair and left the city, the central government in Beijing rang the local authorities in Guangdong to solve the problem.

China’s leader Deng Xiaoping quickly called for the establishment of world-class tourist hotels in major cities. In the summer of 1978, a State Council working group for using foreign investment to build hotels proposed eight projects to receive international tourists in Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Nanjing.

In October 1979, the General Administration of Tourism jointly invested 20 million US dollars with Chinese American Clement Chen Jr. to build the Beijing Jianguo Hotel. The hotel, which was 49 percent foreign-owned (the rest belonged to the Chinese state), opened in March 1982. It introduced an overseas hotel management company, Hong Kong Peninsula Management Group, which appointed a management team of more than 40 people. The joint venture made 1.5 million yuan in profit in its first year.

As economic reforms picked up pace, the appetite for a commercialized hospitality industry grew. In 1984, the Party’s main newspaper, People’s Daily, praised the Jianguo Hotel on its front page.

In 1983, Orville Schell, an American China studies scholar, described his stay at the Jianguo Hotel in the New York Times. “The rooms have wall-to-wall carpeting. The matching drapes and bedspreads are made of bright floral print fabric that seems as remote to China as tropical foliage in Greenland. The private bathrooms are finished with black and white Chinese marble, one of the few interior effects of local origin. The king-size beds are all imported from the United States,” he wrote. “It is a living advertisement for the outside capitalist world with which the denizens of Peking have just begun to become reacquainted after three decades of socialist isolation.”

Schell recorded that rooms cost 60 to 70 US dollars a night (nearly one-third the average annual income in China at the time), three times more than regular hotels that weren’t allowed to accept foreigners. The scholar also observed that except for interlocutors or high-ranking cadres attending official functions, the majority of local Chinese were absent from the hotel. His article was titled: “An Oasis of Privilege in China.”

When Schell interviewed the joint owner Clement Chen Jr., he explained that the grounds were closed to non-guests. “If I let all these people come in, I would have thousands of them arriving for a cup of tea, and then spending the rest of the day sitting around enjoying the air conditioning,” Chen said.

Other foreign-facing hotels were open to all. The White Swan Hotel, opened in 1983 in Guangzhou, was a joint venture with Hong Kong businessman Fok Ying Tung. At 28 stories tall, it dominated the Guangzhou skyline at the time. Though it was luxury (a standard room can cost around 1,200 yuan per night even today), and out of budget for most Chinese, it was open for anyone to roam the lobby and grounds.

In an interview with Nanfang Daily in 2018, Yang Xiaopeng, the former general manager of the White Swan Hotel, described its open policy as “groundbreaking” but also “chaotic” at first. The hotel grounds were often overcrowded with people curious to glimpse inside. “People used 400 rolls of high-end toilet paper on our opening day. You could sweep two big bowls of dust out from under the lobby carper at the end of each day,” Yang recalled.

Many managers wanted to close the hotel to everyone except guests, but Fok refused, according to Yang. He was determined to show the public what the government’s Reform and Opening Up policy looked like in practice.

By the 1990s, China’s travel and tourism industries were growing rapidly. More people needed to travel across the country for business, and as incomes grew, people had money to spend on leisure and tourism. In 2000, domestic tourists in China made over 744 million trips. By 2011, the figure reached 2.64 billion. Budget hotels and chains entered the market, while domestic hotel firms rapidly overtook foreign-owned luxury brands.

Nowadays, zhaodaisuo is a thing of the past and there are 430,000 hotels with 14 million guestrooms nationwide, according to the China Hospitality Association. One of the most popular in the last few months has been the Peace Hotel in Shanghai. It was built by the British in the 19th century but recently went viral for the role it plays in the hit TV show Blossoms Shanghai. Thankfully guests no longer need a foreign passport or an introduction letter from their employer to stay there, though they will need around 3,000 yuan per night.