A tiny enemy nearly brought down the Qing empire

In the 17th century, the Great Qing Empire of the Manchus subjugated the Mongols, waged war against the Joseon dynasty in Korea, and took over the territory of the Ming dynasty in China. But there was one enemy that terrified even these fearsome conquerors: smallpox.

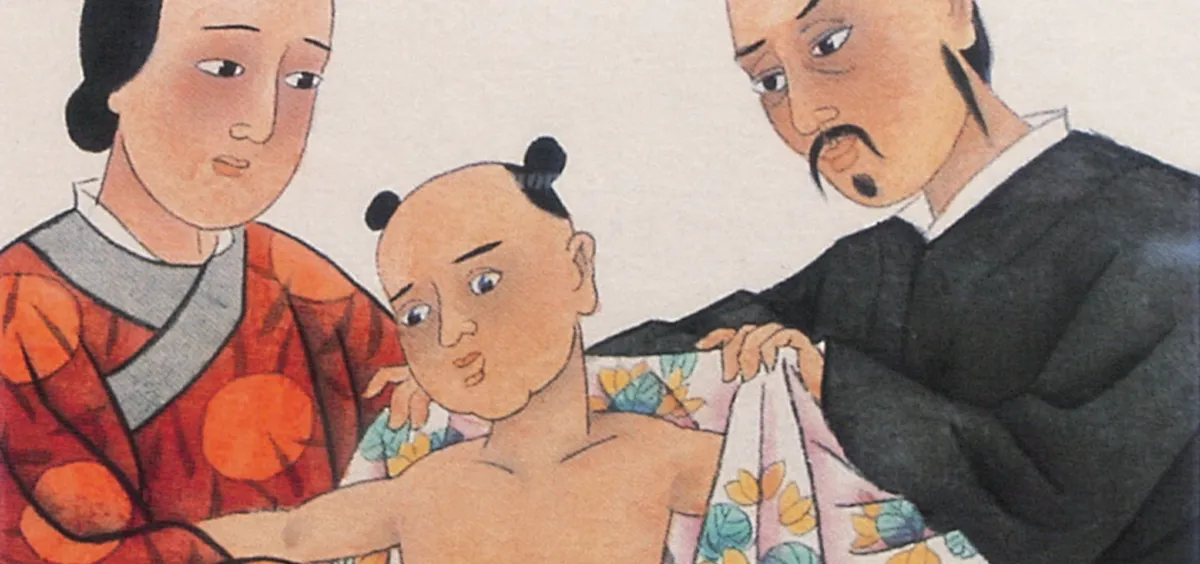

The disease had been endemic in China for centuries. The celebrated third century physician Ge Hong described “seasonal epidemic sores which attack the head, face and trunk” with red boils. “If the severe cases are not treated immediately, many will die,” he wrote. Variolation, a technique that exposed a child to a mild case of smallpox to boost immunity, had been developed by the time of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), and some physicians reported success in preventing 80 to 90 percent of infections.

Smallpox, though, was not prevalent in the remote northern forests and mountains of the Manchu homeland. Few if any Manchus had developed a natural immunity to the disease. The expansion of their empire meant increased contact with their southern neighbors, as well as their illnesses. In 1613, an outbreak of smallpox killed thousands of Manchus. So high was their anxiety over smallpox, members of the imperial Aisin-Gioro family would often refuse to attend funerals of family members who died of the disease.

In 1644, the Manchus allied with ex-Ming general Wu Sangui to expel the rebel armies of Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong from Beijing. Even as the armies of the Great Qing rode into the former Ming capital, smallpox was very much on their mind.

China’s first free variolation center for children, the Bao Chi Tang, opened in Tianjin in 1850

To protect their young Shunzhi Emperor living in the Forbidden City, Qing officials made sweeping changes to their new capital. They ordered most of the remaining Chinese residents in the northern half of the city, which surrounded the palace, to relocate to the southern section. The division between the “Tartar City” and the “Chinese City” persisted, in name at least, down to the 20th century.

The Qing also established a Quarantine Bureau in Beijing to minimize dangerous outbreaks of smallpox. The forerunner of this bureau emerged in 1622, when the Shunzhi Emperor’s grandfather, Nurhaci, ordered his officials to report any cases of smallpox among their troops to stop cross-infections among different military units.

The Quarantine Bureau demanded reports of any suspected cases of smallpox in the city, and would then arrange to have the patients sent away. In the early years of Qing rule in China, the Quarantine Bureau was concerned only with policing the health of the Manchus and other members of the Banners, the socio-military units of the Qing Empire which also included some Chinese and Mongols.

Soon, however, the policies were expanded to include all residents of the capital. Smallpox victims and their families were forced to move far outside of Beijing. Those who refused were executed. Many could not afford to leave, and there were even cases of families killing infected relatives to avoid expulsion from the capital.

The imperial family, for whom smallpox remained a constant worry, took their own preventative measures. The court established bidousuo (避痘所), or anti-pox shelters, where healthy individuals could take refuge during outbreaks. One of the Shunzhi Emperor’s preferred retreats was in the Southern Gardens of Nanyuan, and he took great pains to prevent the contamination of his sanctum by ordering all residents living within a two-kilometer radius to be forcibly removed.

In spite of these precautions, the Shunzhi Emperor became infected with smallpox and died of the disease in 1661. His young son Hiowan-yei took the throne as the Kangxi Emperor. Although he was only 7, the Kangxi Emperor fulfilled the requirement for an heir his father had made on his deathbed: Only those who had survived smallpox, and so were presumed immune from it, could ascend the imperial throne. The young prince had spent much of his childhood semi-exiled in a bidousuo just outside the western walls of the Forbidden City. But even within his sanctuary, the future emperor just barely escaped his bout with the disease.

During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, variolation became common among the Manchus. The practice helped to both reduce the severity of outbreaks and ease the fears of infection by the Qing rulers, now settled inside the Great Wall for a long and prosperous reign.

“A Pox on the House of Aisin-Gioro” is a part of the cover story from our issue, “Contagion”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.