Riding the rails of southern Yunnan province, where “internet celebrity” tourism and French colonial legacy collide

A white speck hurtles toward me, the sound of it growing from a low hum to a roaring whir. Eventually, the distinctive ivory tubes of a high-speed train blast past my car, carrying hundreds of passengers across the lush landscape of China‘s southwestern Yunnan province. The train careers into the distance, suspended above me on raised tracks carved into nature.

This high-speed railway between the provincial capital, Kunming, and Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture, swoops through 10 tunnels and traverses 52 bridges. It stops at five train stations along the way, and took five years and 13.62 billion yuan to build. But I’m not here to spot modern symbols of China’s economic growth: I’m on the trail of railway heritage that stretches back to the late 19th century.

Back then, French colonial ambitions in Yunnan and Southeast Asia collided with a China trying desperately to modernize and escape manipulation by imperialist powers. France built the Yunnan-Vietnam Railway, running south from Kunming to Hekou on the border with Vietnam (then French Indochina)—a colonial project to extract resources from southwest China and transport them to the French empire.

After the Qing dynasty fell in 1911 and Chinese leaders sought to modernize their country and resist further encroachment by imperial powers, the government granted another railway contract in Yunnan to a private Chinese railway company. They built the Gebishi Railway, which ran from Shiping in the west to Bisezhai, where it linked up with the French tracks.

I want to trace the Gebishi Railway, and as the new high-speed train tracks bend away from my car and out of sight, I exit the highway near Jijie, my first stop.

The forgotten station

As I drive into Jijie, I’m slightly surprised by the run-down scene before me. Jijie was a vital stop on the Gebishi line, as it connected to tin mines in Gejiu city to the south. Gejiu’s mining history dates back 2,000 years to the Han dynasty, and the city’s economy is still heavily reliant on tin and lead mining today, but Jijie Station displays little of this former glory.

I pay an unexplained 1-yuan toll to enter a shabby-looking town, but as I trundle down a dusty road for another five minutes or so, faded red characters appear above a crumbling white wall covered in ads: Jijie Station. While I had seen posts on social media about many of the other stations on my Gebishi Railway itinerary, I had found little information about Jijie online. Sure enough, the station is virtually deserted but for a few families meeting up for a sunset picnic atop the now disused tracks.

A mustard-yellow building with grass-green window shades soon catches my attention. There is a collection of these buildings, all of them in old French colonial style, and they make up the remnants of a 3,000 square meter train station. After walking out from the narrow corridor next to one of the old station buildings, I find numerous dusty rail ties and beams that seemingly haven’t been moved since the last trains ran 33 years ago.

The buildings are a reminder of colonialism in China and Southeast Asia, but they weren’t built by the French. Having already built their railway from Kunming to Hekou in 1910, the French hoped to extend the line west to Jijie and Gejiu to connect to the precious deposit of tin there.

But in 1914, in a show of defiance to the imperial powers, the governor of Yunnan, Tang Jiyao (唐继尧), awarded the contract to a group of Chinese merchants. They formed the Gebi Railway Company, and deliberately built their track narrower than the French one (so foreign trains couldn’t use it). Company rules forbade foreign ownership of the railway, but they still relied on foreign engineers for construction and copied much of the French Yunnan-Vietnam Railway—including the French-style buildings, which became a feature of every station on the line.

The line from Jijie to Bisezhai (the eastern terminus of the Gebishi Railway, where it joined with France’s Yunnan-Vietnam Railway) was completed in 1918. Construction from Jijie Station to the mines of Gejiu was completed in 1921, and it began operating as both a passenger transfer station, but more importantly as the station where tin brought north from Gejiu was transferred to head west to Shiping or, more likely, east to Bisezhai. Much of the tin was eventually carried throughout France’s empire and sold internationally, though some was kept in China. In the 1930s, Gejiu’s tin made up 80 percent of the goods transported on the railway at Jijie.

Now, however, the station feels deserted rather than preserved. I take a break to sample Jijie’s roast chicken, apparently a local delicacy (though I can’t discern anything special about it), and then head back onto the highway to follow the Gebishi Railway’s tracks further west, to a station that has been going viral on social media.

Rail tourism in the internet age

After an hour of driving the 54 kilometers to Jianshui county, I find a totally different scene to forgotten Jijie. Tourists are darting around a train station built in 1928, snapping selfies next to the restored colonial buildings and bronze statues of imagined passengers from the 1920s: a cosmopolitan woman dressed in period attire, a young boy selling candied hawthorn berries, and a pigtailed girl slinging packets of cigarettes. Tucked in the corner, behind (mainly empty) train stalls, sits an old British steam locomotive produced in the 1940s, a reminder of the clamorous beasts that once brought tin and other commodities across these railways.

Unlike Jijie, Jianshui Station has made the leap from historical site to “internet famous” tourist destination. On social media platform Xiaohongshu, I found an endless stream of content, mainly tourists and influencers posing at the French-style station, or hopping on and off pretty vintage green and yellow trains.

Many of the stations along the 177-kilometer Gebishi Railway (like Jijie) have become weathered over the years, but Jianshui has been spruced up for visitors. The highlight for tourists is the vintage “small train” which began operating in 2015 and runs 13 kilometers along the old route—though it doesn’t run on the same tracks, since the narrow gauge was widened for the small train.

The train runs twice a day, and the 100-yuan tickets often sell out. I fail to book a ticket online, but get lucky at the ticket office—there are still tickets available for the next morning. “Arrive at 8:40, 20 minutes before your 9 a.m. ride. The train leaves on time every day,” says the ticket seller, pointing sternly at the departure time printed on my trendy orange and red ticket.

I spend the rest of the day exploring more of Jianshui Station, snapping pictures of the buildings along with the other tourists. I also find dozens of brightly painted shipping containers sporting signs for pop-up shops and snacks, but only one shop is open when I investigate.

The station raked in nearly 10 million yuan in 2019, mainly from selling train tickets and food and beverages, before the Covid-19 pandemic wiped out its profits. “It was very hard to make ends meet and continue operating,” says Cao Yun, the train station’s tourism manager, when I inquire about the station’s business.

Now, things seem to be looking up again. When I return the next morning 10 minutes before the train departs, an even larger crowd is milling around: middle-aged and elderly Chinese women posing for photos with their tour groups, children running around, oblivious to the large drop off of the platform, and young couples trying to find the perfect angle of morning sunlight for a romantic snap.

At 9 a.m. sharp the heavy rattling of the train wheels churning begins as we head off on our journey through history. The train chugs along at 25 kilometers per hour carrying us to three stops on the Gebishi line: Shuanglong (“Double Dragon”) Bridge, Xianghuiqiao Station, and Tuanshan Station. The Double Dragon Bridge, built during the Qing dynasty, is made of stone and has 17 arches. It’s not built for trains, but it serves as an excuse for the tourist train’s first stop as we hop off to take more pictures.

The other two stops are picturesque stations, where the main attractions are more French-style buildings and mottled walls dating from the 1930s. There’s not much trace of any deeper reflection on the history of the railway here, or at the final stop at Tuanshan. Instead, a high-end cafe, restaurant, and hotel take up the most space—all of them heavily featured on Xiaohongshu.

On the return trip to Jianshui, I sit next to a group of tourists in their 20s who busy themselves taking photos out the window. I strike up conversation and ask them why they’re here: “My friend, who’s a local, invited us. She says it’s a must-visit here in Jianshui. Plus, I can enjoy the beautiful scenery along the way.” They’ve come from Wenshan, around 200 kilometers east, one of them explains. A few minutes later they pause their intense staring out the window and drift off to sleep.

Back in Jianshui, I’ve arranged another meeting with manager Cao in one of the train’s now stationary carriages. “Jianshui is a special place, with bountiful history that follows along the flowing river,” she gushes, explaining how tourism could become the main driver of Jianshui’s economy.

I’m curious why Jianshui draws tourists and other, equally attractive parts of the railway (like Jijie) remain less well-known. Cao tells me marketing is key, and that Jianshui train station didn’t get it right in the beginning. Investment and cooperation with the Kunming Railway Bureau didn’t yield many tourists, and initial advertising efforts, including a billboard at Kunming’s Changshui Airport, proved ineffective.

Instead, advertising through numerous provincial TV stations, recruiting travel vloggers, and inviting online influencers to sample and share content about Jianshui helped bring tourists in. Not much of it had to do with the station’s history, it seems, but rather its aesthetics.

The site plans to keep growing, Cao says, despite a 2015 plan to drastically expand the area with accommodation, restaurants, and more parking falling through after the site couldn’t agree on compensation with local residents whose houses would have been demolished for the development.

Many local government plans to revitalize Honghe today hearken back to the area’s integration when the Gebishi Railway operated. One project calls for linking Shiping (the western terminal of the Gebishi Railway) and Jianshui via a rail line with multiple stops in between. Another plan for the old Yunnan-Vietnam Railway envisages connecting Kaiyuan and Bisezhai stations via a tourist line.

“You should come back again this November…By then we’ll have extended this line with more stations and have new train carriages,” says Cao as we bid farewell. I take a final glance around the historical station, pondering how much of a change I’ll actually see when I make my return trip.

Where two tracks meet

My last stop takes me back east to Bisezhai, outside the city of Mengzi. Located 177 kilometers north of Hekou, and 288 kilometers south of Kunming, Bisezhai was where the privately operated Gebishi line met the French-owned Yunnan-Vietnam Railway. Trains loaded with tin from Gejiu on the narrow Chinese tracks stopped at a turntable at this meeting point, where locomotives waited to reload the tin and carry it south on the wider French tracks.

In 2016, the local government announced an estimated 5.76 billion yuan project that would transform Bisezhai into a major scenic spot, which is now complete. When I arrive, I find that tourists can’t drive to the station’s entrance, but are instead herded onto small white minibuses from a parking lot next to the highway. At the bus stop, stalls selling souvenirs and snacks line the paths leading up to the railway. After walking through the maze of merchants, I finally see the gravel pits where the train tracks still lie (together with more mustard-yellow buildings).

Bisezhai was vital to the railway a century ago, and it remains perhaps the most famous spot for visitors on the line. The old French station exploded in popularity in China after it appeared in the 2017 film Youth, a drama that follows the members of a young military art troupe in 1979. During the Lunar New Year holiday in 2019, over 200,000 people visited. I wander round the large station area, and find the “‘Youth Movie’ Experience Center,” where tourists are invited to don period People’s Liberation Army uniforms and snap photos as if they were in the film.

The local government’s grand development plans for the area are already in motion: the expanded parking holds over 400 cars and further expansion aims to turn the surrounding villages into a “rural tourism hub.” They have already drawn up new plans for roads that connect selected villages and large-scale campsites. Hikers often roam all or part of the 80 kilometers from Bisezhai to Renziqiao, a famous bridge on the Yunnan-Vietnam Railway.

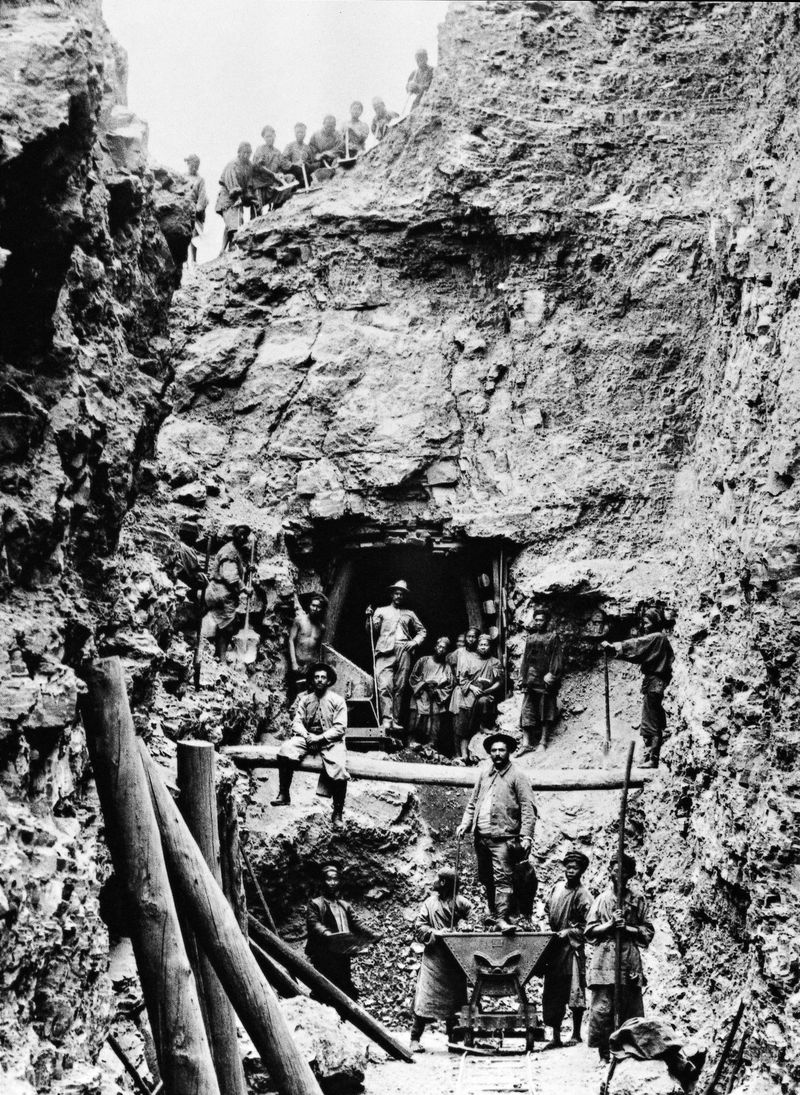

At Renziqiao, the legacy of France’s colonial ambitions in Yunnan is at its starkest. The 115-year-old bridge straddles a 65-meter-wide gorge in between two mountains 102 meters above the Sicha River. It was a feat of engineering when completed in 1908, but came at a terrible human cost—an estimated 800 Chinese laborers died during construction, or around 12 lives lost for every meter of bridge laid. Today, a plaque at Renziqiao carries a quote from an unnamed French engineer involved in its design: “For each sleeper laid, a life taken, for each spike, a drop of blood.”

The bridge and railway here helped supply Allied troops after Japan invaded China, and were finally brought under Chinese control in the 1940s, once Japanese forces were pushed back from Yunnan. After 1949, freight continued to travel along the line, including supplies to communist North Vietnam in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Passenger trains at Renziqiao ceased in 2005, but freight trains still run along the tracks once a day, with tourists gathering on viewing platforms on the bridge to watch the trains pass.

Though the station continues to attract visitors for its beauty, the Yunnan-Vietnam Railway’s colonial history remains controversial in academic circles. The railway, and Renziqiao specifically, have been suggested as potential Chinese applicants for UNESCO World Heritage status, but some scholars and officials question whether this would downplay the suffering that resulted from these treacherous construction projects and the legacy of colonialism as a whole.

These debates run through my mind as I take my last photo of Bisezhai’s French-inspired architecture, and peer into the distance at the rows of train tracks that trailblazed modernity into Yunnan. Hopping back into my car, I take a minute to map out other remote train stations that have yet to be engulfed in tourist development, and pull out onto the highway. Off into the distance, over Honghe’s luscious green hills and mountainous landscape, a familiar white speck speeds closer and closer.

All Aboard the Yunnan Express is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.