Hainan is at the forefront of China's booming underwater archeology field

It was the Southern Song dynasty (1127 – 1279) and the economy was booming—on the sea. For centuries, the Silk Road stretching westward across the Asian continent had been China’s lifeline to the rest of the world. In return for its tea, silk, and porcelain, China imported products from exotic places like Persia and India. Material goods were not the only things to travel along the Silk Road, however; ideas, philosophies, and religions spread like wildfire. During the earlier Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Buddhism was introduced to China through India via this influential trade route.

By the time the Southern Song dynasty had rolled around, though, the overland Silk Road had become increasingly unsafe and expensive for merchants to travel due to political tensions in Central Asia. The Song responded by investing in a new solution: a maritime Silk Road, which quickly exceeded overland trade. The Song government sent merchants across Southeast and South Asia, establishing new and lucrative avenues. Although the extent of the Song’s economic influence is still being unearthed, shards of Song porcelain have been found as far away as the east coast of Africa.

Due to its location in the South China Sea, Hainan has been at the forefront of an exciting new field that aims to restore our knowledge of China’s ancient Maritime Silk Road: underwater archeology. So often is archeology associated with shovels and dirt sifters, it may be hard to imagine archeologists in wet suits and flippers, carefully unearthing shipwrecks on the ocean floor. That is, however, just one aspect of this extreme and costly endeavor: China’s underwater archeological initiatives also include deep-sea excavations. Within a relatively short amount of time, China has become a major player in underwater archeology. In 2010, it became the fifth country in the world to have a manned ship able to descend 1,000 meters under the sea.

The reason for China’s seemingly meteoric rise in underwater archeology lies in a little-known event of 1986, when British treasure hunter Michael Hatcher extracted Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) porcelain from a Dutch ship near Indonesia. Although the Chinese government attempted to get the artifacts back, Hatcher reportedly profited some 20 million USD by selling the loot. Realizing the massive money-making opportunity, others—from professional looters to poor fishermen—began to follow suit, finding shipwrecks and selling the valuable booty for profit. To protect the treasures around its own coast, China created the Center for Underwater Archeology in 1987, which has since grown substantially. There are now around 100 underwater archeologists in the country, 22 of whom are based in Hainan.

When Chinese fishermen discovered a 20-meter-long boat only 3 meters underwater in 1996, nobody knew how many times it had been looted. According to experts, the boat had already suffered severe damage from robbers, who had taken most items of monetary value. Discovered at Huaguang Reef (华光礁) in the Xisha Islands, the ship was assumed to be a merchant vessel that struck the reef and sank in one of the area’s many storms. Indeed, the area has proven to be a proverbial treasure trove for ancient Chinese shipwrecks; some 136 underwater archaeological sites were discovered around the Xisha, Nansha, and Zhongsha islands in the South China Sea.

Due to its proximity to the shipwrecks, Hainan quickly became a place where excavations could be efficiently organized. In 2007, excavation began on the shipwreck discovered in 1996, now called the Huaguangjiao I (华光礁I号) in honor of the reef on which it was found. As one of the oldest shipwrecks discovered and excavated by the Chinese in the South China Sea, the Huaguangjiao I represented a milestone for China’s underwater archeology. Remains of the ship and artifacts are now on display at the Hainan Museum (海南省博物馆) in Haikou, which played an integral role in organizing the excavation.

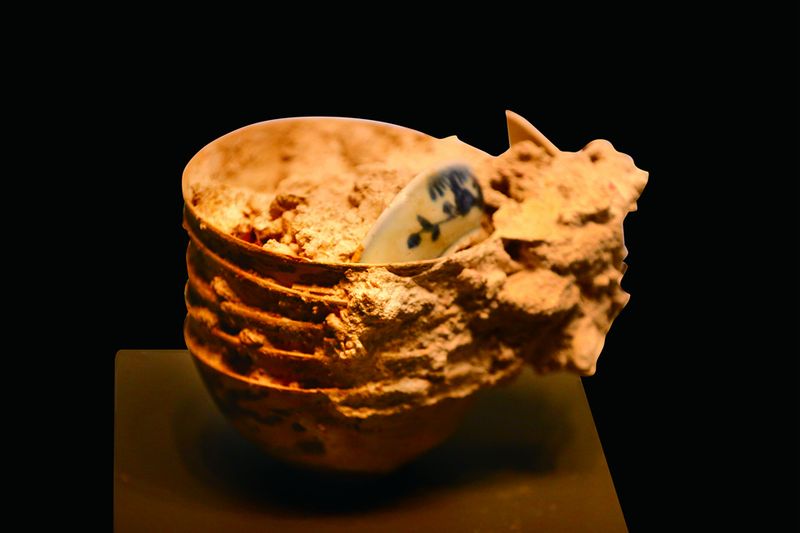

Built between 1127 and 1279, the wrecked ship was transporting Song porcelain and other cargo during the peak of China’s ceramics industry. Since most of the looters were likely looking for copper coins and other objects of intrinsic value, they left many of the porcelains underwater (and even broke them in the attempt to extract more valuable objects). The Huaguangjiao I proved to contain a substantial number of cultural objects, including 511 pieces of boat decks, over 10,000 pieces of porcelain, and 100 iron artifacts.

As many of the artifacts were broken, compressed, or eroded over time, the Hainan Museum organized a preservation and conservation team made up of five experts. Their research facility can be visited at the museum, which was opened to the public in 2008. Thus far, over 9,500 of the ceramic objects have been repaired and studied, providing new insight into domestic ceramic production, as well as ancient overseas trade routes.

Historians have been able to determine that most of the Huaguangjiao I’s porcelain came from kilns of the coastal Fujian province. However, some of the greatest treasures found in the wreckage were the rare greenish-white glazed porcelain pieces from the famed Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province. What excited many of the historians are characteristics which show that these ceramics were clearly meant for export, rather than for domestic use. Some pieces on display at the Hainan Museum include the Chinese character 吉 (jí), meaning “good fortune,” an aesthetic element that was especially popular in Chinese immigrant communities in Southeast Asia during the Song dynasty.

The Hainan Museum is free to enter and foreigner-friendly, with signs in English as well as a guided audio tour in multiple languages. Much of the first floor is dedicated to the Huaguangjiao I and underwater archeology, including a 360-degree multimedia video explaining how the ship was salvaged. Other displays show a range of artifacts excavated around the Xisha Islands, including statues and architectural elements, which experts believe to be remains of temples built by ancient fishers to pray for safe seafaring. Another exhibition describes ancient shipbuilding techniques that allowed Song dynasty boats to become some of the largest vessels on the oceans during that time—perfect for filling up with goods for trading.

The focus on underwater archeology should come as no surprise to those familiar with the museum: Its Underwater Archeology Research Center is the base for 12 underwater archeologists. They divide their time between the museum and the boats that take them to shipwrecks up and down China’s coast—from the relatively cold-water and low-visibility seas of Shandong and Zhejiang up north, to the warmer, clearer waters of the South China Sea.

With so many shipwrecks from different eras on the ocean floor, each archeologist has developed a specialization, and some are able to tell a priceless artifact from a common rock with the naked eye. Not only do these archeologists have to be excellent swimmers and top-level historians, they must also study a plethora of subjects from ancient shipbuilding (to determine where artifacts might be stored, as well as if the boat was actually Chinese) to geological shifts, ocean currents, and ancient maps, in order to locate where a ship might have eventually sunk in the ocean.

Since the Huaguangjiao I, many other underwater digs have originated from Hainan. Each project typically takes several years to complete due to weather and ocean conditions. Normally, an expedition will last for a month or two, and will continue at the same time the following year. To make matters even more difficult, sometimes there are no remnants of a ship at all, just myriad priceless items buried in the sea floor.

Many of the discoveries are also housed at the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea [中国(海南)南海博物馆], a massive complex in Qionghai, a city best known for hosting the annual Boao Forum for Asia. The museum is an attraction in and of itself, with sleek clean lines that resemble a ship, open windows that let in light, and decks that allow visitors to enjoy tropical plants and the ocean nearby. There is one hall dedicated to the discovery of the Huaguangjiao I, as well as two halls focused on the history of underwater excavations and cultural heritage protection in China, one of which includes a life-sized replica of a submerged ship. These halls tell the story of shipwrecks like the Nan’ao I (南澳I号), a Ming dynasty merchant ship loaded with china, pottery, metalware, and more; and the Nanhai I (南海I号), another Song dynasty ship that was extracted whole from the ocean floor and is now preserved in the Maritime Silk Road Museum of Guangdong (广东海上丝绸之路博物馆) on the mainland.

Both the Hainan Museum and the China (Hainan) Museum of the South China Sea also tell the oft-overlooked history of the far-flung frontier island. Separated from the Chinese crux of power, Hainan locals relied on basic industries like agriculture, fishing, and salt-making for centuries. The sea also provided opportunities for historical mingling: Hainan was an immigrant island, with a culture shaped by the different ethnic groups that settled there. The earliest Li ethnic minority were followed by China’s largest ethnic group, the Han, who began to immigrate to the island during the Han dynasty—followed by the Hui Muslims in the Song (960 – 1279) and Yuan (1206 – 1368) dynasties, and the Miao during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644).

Journeying with Jianzhen

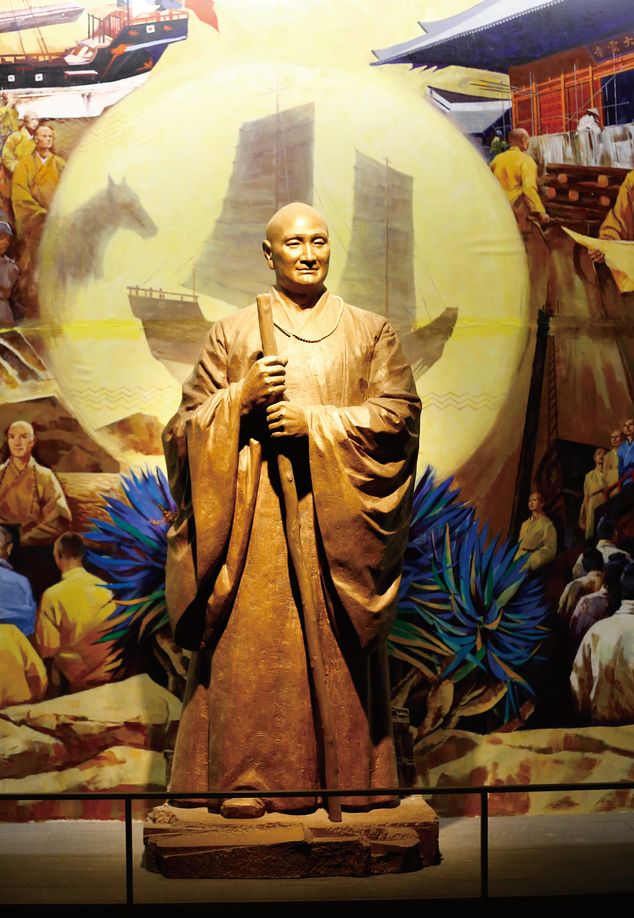

Jianzhen, a prominent monk who lived during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), was known for making six attempted voyages to Japan. He eventually succeeded, and brought the “five Buddhist precepts” to China’s neighbor across the sea. His quest is said to have spearheaded the spread of Tang culture within Japan, an influence which is still felt to this day in the country’s architecture, literature, and written script. The Japanese bestowed Jianzhen with the title “Cultural Benefactor,” and he remains a symbol of ongoing Sino-Japanese cultural exchange.

Though it’s widely known that Jianzhen had to overcome many hardships before he finally arrived in Japan, few are aware that on his fifth voyage, he was shipwrecked in Hainan. In 748, Jianzhen and his entourage were struck by a typhoon, drifted wildly off course, and washed up on the beach of Zhenzhou (振州), today’s Sanya. Warmly welcomed by locals, Jianzhen took up residence at the Dayun Temple (大云寺) and helped to reconstruct it. He promoted Buddhism in Hainan until he was able to leave the following year.

Today, in Sanya’s Daxiao Dongtian Scenic Area (大小洞天风景区), visitors can admire a statue of Jianzhen, part of a scene depicting the ship’s landing on Hainan’s shores. The statue faces the sea, as if Jianzhen is wondering when he can start his next adventure.

Cover image by VCG

Excerpt taken from Hainan: Jade Cliffs to Ocean Paradise, TWOC’s new guide to China’s southernmost province. Get your copy today from our WeChat store!