How a 19th-century act of “corporate espionage” changed world history

In the mid-17th century, tea found its way to the coffeehouses of London, and by the mid-18th century, the drink was so widespread that Chelsea began manufacturing imitation Chinese tea ware. The famous English “tea time” tradition was an invention of the 1830s, more specifically by Anna Russell, Duchess of Bedford. For over 200 years, the British were obsessed with tea—all without knowing how it was made or exactly what it was made from.

Much like silk, the secret of tea was a closely guarded secret in the Middle Kingdom, a staple from China almost unparalleled in the history of trade. Back home in England, botanists argued vociferously over dried specimens of tea leaves, claiming that black tea and green tea obviously came from different plants. But this was all just guesswork, as no European botanist had ever gotten their hands on living tea plants to study, much less understood the arduous process by which it was made.

The argument was put to bed by Scottish botanist Robert Fortune, who first went to China in 1843 as a collector for the Royal Horticultural Society. Rather than bringing back knowledge of orchids and shrubs, Fortune returned from his first trip with tales of vicious pirates on the Yangtze River, hateful anti-foreigner mobs, and a whole slurry of other adventures that took England by storm in his book, Three Years’ Wanderings in the Northern Provinces of China.

Despite the many baseless, racist diatribes on the character of the Chinese, Fortune certainly had an odd love for the Middle Kingdom. He wrote, “All along the coast, at least as far as [Zhejiang], richly deserve the bad character which everyone gives them; being remarkable for their hatred to foreigners and conceited notions of their own importance…are nothing less than thieves and pirates. But the character of the Chinese as a nation must not suffer from a partial view of this kind.”

He traveled through Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Fujian provinces to study the secret of tea. Back home, the science of the time split black and green tea into two types: Camellia bohea and Camellia viridis respectively. However, Fortune’s studies yielded a stunning discovery. He explained in his book, “Those who have had the best means of judging have been deceived, and that the greater part of the black and green teas which are brought yearly from China to Europe and America are obtained from the same species.” Because of him, the taxonomy changed—from Camellia bohea and Camellia viridis into Camellia sinensis, tea from China. The difference was nothing more than a minor change in the creation process, in that black tea was made from leaves that had oxidized.

His discovery, studies, and gunfights with pirates also yielded the important fact that Chinese teas from Guangdong province were dyed. Europe and America at the time enjoyed what they thought was the natural color of tea in water, calling it a “beautiful bloom” of color. Fortune discovered that these effects were made with a type of paint known as Prussian blue (iron ferrocyanide) to suit the tastes of the foreign “barbarians,” essentially making green tea greener.

His writings, which would soon become popular around England, seem to embody the mystical, tragic heart of the explorer. In referring to attempts to understand and explain China, he says, “We were in the position of little children who gaze with admiration and wonder at a penny peep-show in a fair or marketplace at home. We looked with magnifying eyes on everything Chinese; and fancied, for the time at least, that what we saw was certainly real. But the same children who look with wonder upon the scenes of Trafalgar and Waterloo, when the curtain falls, and their penny-worth of sights has passed by, find that, instead of being amongst those striking scenes which have just passed in review before their eyes, they are only, after all, in the marketplace of their native town.”

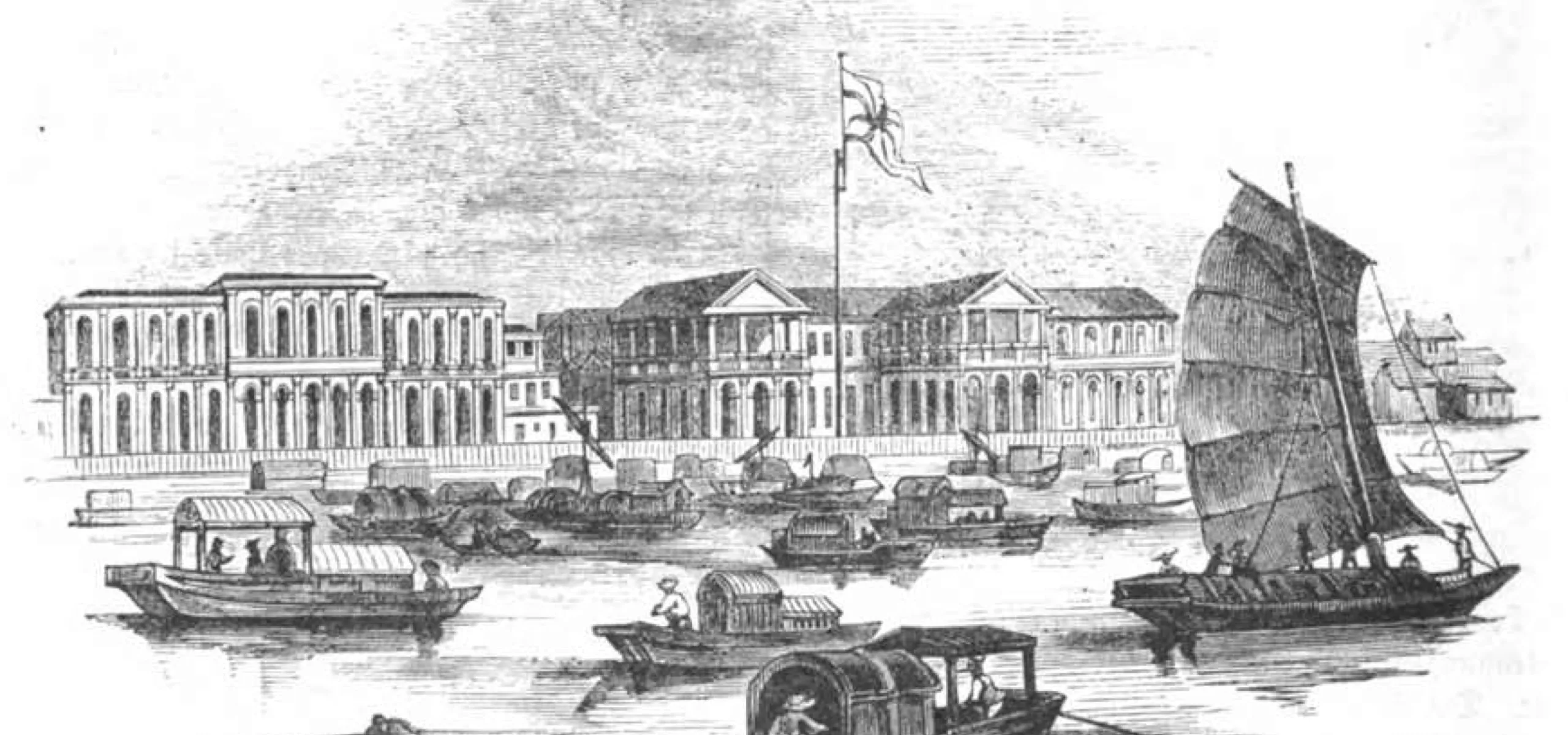

Fortune returned to Britain, but history was not done with the great adventurer-botanist. Knowing that black tea and green tea are from the same plant was all well and good, but China still had a monopoly on the trade. The powers at home wanted to regulate the price of what had become by far the most popular drink in the country. The Opium Wars were expensive, and the East India Company knew that they needed a more cost-effective method of getting tea rather than just exchanging it for opium. They needed a spy. Who better than Robert Fortune?

Fortune’s knowledge of tea and China made him the perfect agent. His next trip to the Middle Kingdom had a mission: to gather live samples of tea to be cultivated by British-controlled India, eliminating reliance on the Chinese stock. Fortune’s second trip to China would have trade repercussions that would last for the next century.

His writings of this time would be collected into A Journey to the Tea Countries of China, published in 1852. The book records many fantastic exploratory gems: observations on opium smoking, advice on shaking a Chinese spy, musings on Chinese culture, and close calls with angry boatmen.

Dressed in Chinese garb, Fortune assumed the persona of a wealthy Chinese merchant from a distant province looking for tea, traveling well beyond the areas allowed to foreigners by treaties of the time. He even had his head shaved, as was the custom, commenting on his barber’s skills, “I suppose I must have been the first person upon whom he had ever operated, and I am charitable enough to wish most sincerely that I may be the last. He did not shave, he actually scraped my poor head until the tears came running down my cheeks, and I cried out in pain.” But all of this paled in importance to Fortune’s ultimate mission of obtaining tea plants for mass harvest.

He was able to send well over 20,000 plants and seedlings to the Himalayas for cultivation by the British, and the effects were drastic.

While Fortune was able to introduce over a 120 plants overall to the West, his work also turned the tea trade in the East on its ear. With the East India Company able to make its own tea, India, not China, became the most important tea-producing nation in the world. This would remain in effect until the middle of the 20th century. Perhaps the most comprehensive book on the subject in English is by Sarah Rose, author of For all the Tea in China; she said in an interview with NPR in 2010, “China has pretty much never really come back from that, certainly not in the Western markets. Now that Asia has such a booming economy, the Chinese are again pretty fierce tea producers. But it took a hundred-plus years.”

Fortune wrote that because of his mission, “The Himalayan tea plantations could now boast of having a number of plants from the best tea-districts of China.” His actions helped fuel the British Empire via the trade of tea for some time to come, described by some as the greatest and most successful act of corporate espionage in history.

By all estimations, Fortune’s career was a success, and his contributions to the world of botany are incalculable. Fortune would return to China once more and then opt for Japan for further travels and exploration. His achievements were myriad, but perhaps none changed history of much as his audacious heist of the secret, then the seedlings, of all the tea in China.

This is a story from our archives. It was originally published in 2015 in our issue“Startup Kingdom” and has been lightly edited. Check out our online store for more issues you can buy!