The chancellor who inspired a generation of Chinese students with his commitment to academic freedom

It was May 1919, and from a small desk in his simple office at Peking University, Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培) could see the campus buzzing with activity. For days now, his students–and several of his faculty–had been busy giving speeches, preparing pamphlets, and painting signs denouncing imperialism and the fecklessness of the Chinese government.

Cai’s students viewed themselves as saviors of the nation. They were heirs to a tradition of scholar activism which had long frustrated emperors and autocrats of imperial times, yet they were also the vanguard of a new kind of Chinese citizen: informed, cosmopolitan, and not always bound by conventional norms.

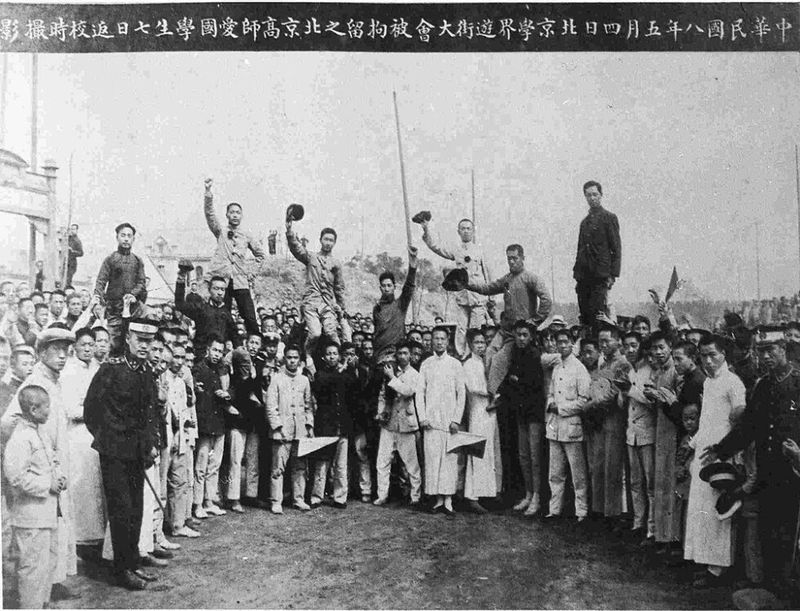

A frugal administrator, humble scholar who refused to ride rickshaws, and a fierce intellect, few figures bridged this gap between old and new China with as much finesse or intellectual firepower as Cai. As chancellor of Peking University, Cai had instilled the values of free thinking in his students, writing in 1919: “With regard to ideas, I act according to the general rule…of tolerating everything and including everything.” When many of his students were arrested for their part in street demonstrations on May 4 that year, protesting China’s betrayal by Japan and the Western powers at the Paris Peace Conferences, Cai resigned in solidarity with them—not the first, or the last, time he would choose academic integrity over political expediency, or even his own safety.

Born in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, on January 11, 1868, Cai had a thirst for knowledge from a young age. He received a classical education and traveled to Beijing at age 25, where he placed 37th in the country in the imperial examinations and earned the highest level jinshi degree in 1892. He was then assigned to the Hanlin Academy, an official library and administrative center with roots dating back to the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), where talented scholars in the 19th century waited for an official position to open. It was a conventional path followed by generations of scholars in China’s history, but Cai was born in an exceptional time, the kind of era which forces the ambitious and gifted to choose between following convention or taking bold action.

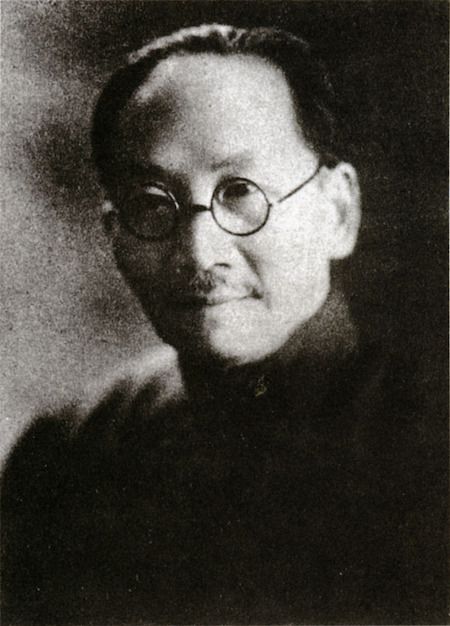

Cai Yuanpei in 1927 (VCG)

By the turn of the 20th century, the Qing dynasty was in disarray, shocked by the events of the Boxer War and held sclerotic by political conservatism and factional infighting. Cai had grown increasingly frustrated with Qing rule, and organized a political association called the “Revival Society” in Shanghai, while he studied German at night and dreamed of continuing his education in Europe. Cai’s activities did not go unnoticed either by the Qing state or its enemies. Allies of the political organizer Sun Yat-sen (孙中山) reached out to Cai, and in 1905 the Revival Society was incorporated into Sun’s Tongmenghui, an alliance of anti-Qing organizations—Cai had become a revolutionary.

In 1907, Cai finally fulfilled his dream to study in Germany, enrolling as a 40-year-old at the University of Leipzig, where he studied psychology, philosophy, aesthetics, and pedagogy. He absorbed the teaching methods used in Europe, always with his home country in mind. When revolution broke out in 1911, Cai, like many republican sympathizers in exile around the world, returned to China eager to participate in the building of a new nation. In 1912, he was appointed the Chief Education Officer of the new provisional government and began on plans to replace the traditional Confucian curriculum with education methods he had experienced in Europe..

But Cai’s first foray into republican government would prove short-lived: True to his principles once more, Cai resigned in 1912 as the dictatorial tendencies of President Yuan Shikai (袁世凯) grew. Cai sided with Sun Yat-sen in the latter’s attempts to overthrow Yuan in 1913, and following the failure of this “Second Revolution,” Cai once again fled into exile.

But Cai continued to work for a better future for China and its people, organizing a series of programs that brought Chinese workers and students to France. Some of these laborers made critical contributions in World War I, risking—and in many cases losing—their lives digging trenches, offloading ships, and providing crucial logistical support in the war against Germany. The programs also offered Chinese students, including future leaders Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai, an opportunity to live and study abroad.

Meanwhile, Yuan Shikai’s political aspirations were evaporating and he died of uremia in 1916. Yuan’s death cleared a significant obstacle for Cai to return home, but the strongman’s demise also left a power vacuum that threatened to consume the fragile government and break apart the country.

From 1916 until 1926, China descended into chaos and violence. Warlords, many acting as proxies for foreign powers, battled to control land and resources, while the central government struggled to exercise authority outside the capital. For the generation coming of age at this time, the situation could not have been more dangerous. But that same sense of impending catastrophe also inspired young people, particularly the privileged elite who could attend China’s few universities, to read widely, think broadly, and to consider all possible ideas in their quest to save China.

Students and other protesters demonstrate during the May Fourth movement (Wikimedia Commons)

Cai’s would play his own part in fostering that spirit as chancellor of Peking University, a position he assumed in 1916, where he promoted his academic philosophy of “freedom of thought and inclusiveness.” He backed those words with actions, hiring an eclectic teaching faculty that included Chen Duxiu (陈独秀), the firebrand publisher of the radical journal New Youth, as his Dean of Arts and Sciences; young scholar Hu Shih (胡适), then only 26 years old and still working on his doctorate thesis at Columbia University in New York, the painter Xu Beihong (徐悲鸿), recently returned from Japan; and the iconoclastic philosopher Liang Shuming (梁漱溟) as a lecturer in religious studies. Peking University swiftly became the epicenter of what was later known as the New Culture era.

Resigning over his anger at the government’s decision to use force during the May Fourth demonstrations in Beijing, Cai returned to the university later in 1919 and oversaw the admission of its first female students in 1920, before resigning for good in 1922,

In 1926, after a brief period in Britain and France, Cai began to work with the newly formed government of Sun Yat-sen’s successor, Chiang Kai-shek. During this time, Cai established two of his most lasting legacies, founding the National College of Music (which became the Shanghai Conservatory) and the research institute Academia Sinica, which is now headquartered in Taipei and remains an influential center of research. But Cai was never entirely comfortable with Chiang, and was appalled at the regime’s willingness to use political violence against their critics in academia.

Cai gradually withdrew from public life and died in Hong Kong in 1940 at the age of 72. But his commitment to open discussion and academic integrity left a lasting mark on the period, and he is still regarded as a hero today. In 1919, he wrote: “Regardless of what schools of academic thought there may be, if their words are reasonable and there is cause for maintaining them, and they have not yet reached the fate of being eliminated by nature, then even though they disagree with each other, I would let them develop in complete freedom.”

This is as true today as ever.

Cover image from VCG