In Chinese politics, it’s difficult to know what’s left

Read part one of the article here.

Among the New Left, and indeed the Party itself, there is a widespread fear of historical nihilism—the idea that certain people, especially rightists, are attempting to manipulate certain aspects of history, particularly the Cultural Revolution. Virtually every leftist I spoke to defended this period to at least some degree. “People are coming out to repent for their crimes during the Cultural Revolution; they want to apologize and negate what happened, but they are not anti-Cultural Revolution heroes and they should hold direct responsibility. Mao promoted a verbal not physical struggle,” said Mai. Professor Li offered a similar response: “Mao was simply a historical representation of the period. As an individual, he could not move and change hundreds of millions of people. Instead the historical actions of hundreds of millions of people found their personal expression in Mao.” Debates about the Cultural Revolution and the redness of Bo Xilai aside, a crucial issue for Chinese New Leftists, and indeed leftists the world over, is if the radical social change they want should come from the bottom-up or the top down; in essence, revolution or evolution? To answer this question one first needs to know to what extent there are any leftists in the Party at all. Surely, if the left want to affect real social change, a position in the party might not be so bad. When the question was put to Zhang Xia, editor of leftist journal The Red Years, she looked at me quizzically, simply saying: “The Party? Why should we join the Party?” An editor at Mao Flag is equally cynical: “Some say there are ‘healthy elements’ within the Party, but I don’t believe it. How can you expect change to come from those detached from the people?”

If the New Left were to have a figurehead, and it is a label he would quickly reject, then it would without doubt be Wang Hui, professor at the departments of history and literature at Beijing’s Tsinghua University and one of China’s leading public intellectuals. In a quiet corner of the University, he answers my questions thoroughly and at length, refusing to see any issues in simple terms of black and white (or even red). Though on a personal level he rejects the label New Left, he gives detailed analysis of the issues that saw the New Left rise, citing the privatization of SOEs, the agricultural crisis starting in the 90s, and the desperate need for social welfare and medical care throughout China. Perhaps befitting his very public position, Wang’s politics seems to take on a more liberal, nuanced hue than other leftists, and he believes that these, so-called, “healthy elements” within the party do exist, at least to some degree: “The division between the people and the Party is gone. Any elements you can find in the society, you can find in the Party, perhaps not at the elite level, but it must exist.” At the suggestion that Bo Xilai represented these elements, Wang is dismissive, and while he points to many aspects of the Chongqing model that proved useful in terms of social equality, he quickly says: “I have no way to know if Bo was an opportunist or a leftist. We don’t know if the trial is right or wrong or true or false. Who can say about his private life?”

As is often the case with Party diktats, the message is unclear, and, strategically at least, Maoism seems to be being embraced at some level amongst the senior echelons of the party, but many suggest this is more about political rhetoric than anything else. On April 22, 2013, the Central Committee of the CPC sent out a communiqué, later dubbed Document Nine, to all local divisions of the Party; incredibly spiky in tone, it warned Party cadres to guard against what it saw as several worrying ideological threats, including the promoting of neoliberal thought and the promotion of historical nihilism. Such words could easily have been written by any number of New Leftists, many of whom firmly warn against these two very things. Confusingly, the document also warned against those critical of the Reform and Opening Up policy. It was seemingly a paper that, if needs be, could lead to the exclusion of

those on the right or left.

Pushed for answers regarding the government’s relationship with capitalism, Professor Wang says: “The government is not unified either. It is a combination, and there are different perspectives within the government. Obviously over the last decade it is perceived that that there are conflicts and debates within the party too. So, it is difficult to think of the party as a unified thing…As an organization, it is unified, but still you find different forces there. But now, in the economic field, the neo-liberal ideas are strong, very strong. Look at the position from the third plenum; they think the market should be given a decisive role in terms of allocation of property and resources. The rhetoric is neoliberal.”

When they aren’t arguing amongst themselves, then capitalism is enemy number one for the New Left, though there is no consensus on how this should be dealt with. Professor Li holds what is in many ways a classic Marxist view of history and sees capitalism itself as laying the seeds of its own destruction, offering the damming verdict: “The Chinese capitalist model has been based on the intense exploitation of a large cheap labor force as well as cheap energy and natural resources. But within a decade, we’re likely to see the surge of working class militancy. Moreover, resource depletion and environmental degradation are likely to break critical thresholds.” Li even goes as far as to say that these thresholds combined with social crisis will lead to the complete downfall of the capitalist system in China, possibly by as early as 2020.

The idea of working class militancy is not a new one, and—certainly as the gap between the haves and the have-nots grows—it stands to reason that there are going to be a lot of angry, disenfranchised workers and even mass unemployment, but capitalism collapsing in China within a decade strikes many as far-fetched, to say the least. When presented with Li’s “the-end-is-nigh” scenario for Chinese capitalism, Wang laughs. It turns out Wang and Li are longtime friends, and I suspect they have had these debates themselves, long before our conversation; Wang clearly has little time for wholesale revolution: “Yes there has been an intensification of social conflicts, but it hasn’t been nationwide. But, in 20 or 30 years…it could be disastrous. In order to avoid that, and I don’t just mean revolution, you need the change to start now. But of course we need radical change, not these kinds of small changes. These kinds of changes only shift and maintain stability for those at the top.”

If those on the left do not think revolution, with all the bloodshed that it historically entails, then what do they want? “We need big social experiments. Economically speaking, [China] will continue for decades but it won’t collapse. Social conflicts will intensify, but that doesn’t mean it will burst. Look at 1930s America, it became a big power and there was huge social conflict, and these were the conditions for the New Deal.” When asked if China could perhaps have some sort of new deal, it is the first time he does not give a long, involved, analytical answer, simply saying, “I hope so.”

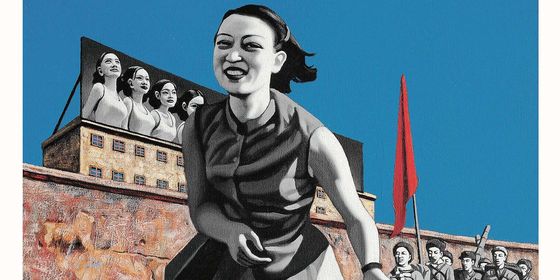

Workers, bloggers, activists, students, and scholars—the New Left come in many different shades of red. Whether bookish academic, or angry protester, their fears form a consensus of sorts. A country that concentrates wealth in the hands of so few while, according to the World Bank, up to 250 million people live on less than $2 a day is surely a ticking time bomb; with such vast reserves of currency, is it too much to ask for a decent health system for those that need it? One thing remains certain, as long as the chasm between the rich and poor continues to relentlessly grow, those on the left will not go away quietly and will continue to fi ght for a social equality that they believe is not only just, but necessary. As things stand, it is easy for things to look bleak for those on the Chinese left, but they continue to believe, as Shi Mai said, “Regarding the future, we are optimistic. We believe history moves in zigzags, but it will be bright. Salute!”