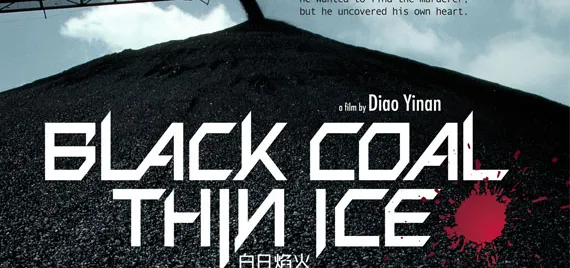

Diao Yi’nan’s critically acclaimed murder mystery

The first 10 minutes of Black Coal, Thin Ice convey a jumbled mix of juxtaposed images, including a dismembered hand traveling down a conveyer belt of coal, a gunfight, the messy divorce of protagonist police captain Zhang Zili, all split between dark, gloomy landscapes in an unknown northwestern Chinese city.

Taking home the Golden Bear for Best Film and Silver Bear for Best Actor at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, Diao Yi’nan’s Black Coal, Thin Ice is the most recent addition to an ever-growing library of internationally well-conceived Chinese cinema. The film opened to 12.8 million USD, making it the highest-earning Chinese-language film of all time. It was recently revealed that Black Coal garnered a slew of high-profile backers, including American rappers 50 Cent, Timbaland, and Eminem and basketball players Carmelo Anthony.

Black Coal, Thin Ice presents itself as a gritty murder noir with nods to French art house—compared with the dynamic shot-composition of modern commercial filmmaking, Black Coal is coldly detached in its narrative eye.

The movie begins with body parts discovered in shipments of coal, across one of China’s northern provinces.

Local police officer: This is the worst I’ve seen. Body parts being dumped, scattered across the whole province. Rumors of corpses in coal piles, everyone scared to come to work. If you can’t crack this case…

Méi jiànguò zhème pāoshī de, xiàng tiānnǚ sănhuā rĕng de quánshĕng nă ér nă ér dōushì. Hăoxiē chăng tīngshuō méiduī xiàmiàn yŏu sĭrén dōu bùgăn kāigōng le. Rúguŏ nĭmen hái pòbùliăo ……

没见过这么抛尸的,像天女散花,扔的全省哪儿哪儿都是。好些厂听说煤堆下面有死人,都不敢开工了。如果你们还破不了……

Investigator: I found something! Liang Zhijun! His name is Liang Zhijun! I’ve got bloody clothes and a ID card!

Zhăodào le!Liáng Zhìjūn!Sĭ zhĕ jiào Liáng Zhìjūn!Zhè yŏu shēnfènzhèng hé xiĕyī ne!

找到了!梁志军!死者叫梁志军!这有身份证和血衣呢!

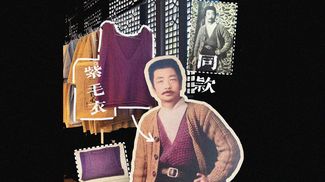

Dismissed police captian Zhang Zili slowly becomes enamored with Wu Zhizhen

Actor Liao Fan (廖凡), who won the Silver Bear for Best Actor, plays police captain Zhang Zili, who is investigating the body parts. Zhang is subsequently wounded in a shootout at a hair salon, which results in the death of his two colleagues and his dismissal from the force. Five years (and 40 pounds) later, he’s playing the role of detective when more body parts are discovered, prompting a game of cat and mouse that quickly turns into an existential struggle ashe falls in love with a femme fatale who just happens to be deeply involved with these murders. Xiao Wang: This is no way to get sober.

Zhang Zili follows Wu Zhizhen, the film’s femme fatale

Xiao Wang: This is no way to get sober. Steer clear of her.

Zhè yĕ bùshì jièjiŭ de bànfă nĭ biè jiăojú le.

这也不是戒酒的办法,你别搅局了。

Zhang Zili: Who says I want to get sober? I’m just looking for something to do so my life isn’t a total loss.

Shéi shuō wŏ yào jièjiŭ le? Wŏ jiùshì xiăng zhăo diăn ér shì ér gān yàobùrán yĕ huó de tài shībài le.

谁说我要戒酒了?我就是想找点儿事儿干。要不然也活得太失败了。

Xiao Wang: What? Do you think anyone ever wins at life?

Ză de?Nĭ hái xiăng yíngde rénshēng a?

咋的?你还想赢得人生啊?

Zhang Zili: At least it slows down my defeat a bit.

Zhìshăo kĕyĭ shū de màn yī diăn ér ba?

至少可以输得慢一点儿吧?

Police Captain and protagonist Zhang Zili (right) survey the crime scene

The use of coal as the vehicle for the body parts is, without a doubt, one of the more controversial aspects of the film—a subtle jab at the environmental cannibalism of coal, but it also bares the ubiquitous nature of coal in everyday Chinese society. In this way, Black Coal grounds itself in the gritty reality of life; there are no real heroes, nor villains, and we’re left to ponder how the intentions and emotions of these characters are molded by the predicaments, in which they find themselves. Diao’s cinematographic work is minimalist: the static nature of the camera—even during gunfights—provides a bleakly objective view of each character; a stark contrast to the stylized violence of modern cinematic gunfights. Interestingly, the directorial voice of the film comes out most in its sound—the decision to use onset noise—the clanging of steel and coal, the unfiltered white noise of industrial China—matching it in volume with the dialogue, gives it the impression of being filmed surreptitiously. Combined with the minimalist perspectives of the camera, Black Coal sets a dreary and nihilistic tone—the birth of a Chinese noir that seems to emulate the existentially-weary language of Mo Yan or Haruki Murakami.

Like an autopsy report, Black Coal, Thin Ice is dismally monotone in its uncompromisingly bleak portrayal of humanity. Diao, when asked why the film had two different titles in English and Chinese, responded that “Black Coal, Thin Ice” refers to the setting in which the body parts were found and “Daylight Fireworks” a reference to the naïve belief in surreal fantasy as an escape from the banality and cruelty of reality. Together, they form the key motive of the film—the grim nature of reality and the way we naively fool ourselves into believing we’ve escaped it.

Early reviews coldly questioned whether the art-house nature of Black Coal was fit for public consumption, and were quickly put down by its intense popularity among mainstream audiences. This unprecedented popularity has gained the interest of both film critics, who see the success of Black Coal as a new way of creating cinema that skirts political, artistic and commercial borders, and China watchers, who see the film as a seminal victory against censorship for its controversial portrayal of the coal industry and the vulnerability of the police.

If critics are right, and this is the beginning of a mass market appeal for art house cinema, it will continue to feed into the unique position that has been dogging Chinese artists for years. How does one walk along so many avenues of political correctness, while maintaining the individuality and voice of a director’s spirit?

LIAO FAN (廖凡)

Liao Fan is a Chinese actor from Hunan and a graduate of the Shanghai Film Academy. He won the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival for his performance in Black Coal, Thin Ice. He is known for a slew of performances in both mainstream and independent films, including the state-sponsored bloody World War II film Assembly («集结号»), and punk-action comedy Let the Bullets Fly («让子弹飞»)。

DIAO YI’NAN (刁亦男)

Diao Yi’nan is a Chinese film director and screenwriter and a graduate of the Chinese Central Academy of Drama. He has directed three films, all of which garnered acclaim, culminating in his Golden Bear for Best Film at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival in 2014.