Booking train tickets during the Spring Festival migration can be like war; businesses are here to help

The calendar New Year just passed, but the Spring Festival, or, the Lunar New Year, is just around the corner. As the most important traditional festival in China, the Lunar New Year a time when people all around the country go back home to be reunited with their families. Migrant workers, university students, and anyone else who lives away from their hometown have already started booking train tickets since almost two months ago—or at least trying.

It’s already well known that the Spring Festival migration, or 春运 (chunyun), is the most in-demand as well as the most crowded and soul-crushing travel season of the year. As the world’s most populous country migrates home for the holidays, it’s extremely difficult for anyone to buy a train ticket successfully. This year, the National Development and Reform Commission predicts that 3.56 million passengers will travel over the railways during chunyun, which is a 9.7 percent increase from last year. The war of tickets is doomed to be fiercer than ever.

In the past, people engaged in this battle by lining up at the railway station in advance of the ticket-release schedule, which can be anywhere from 10 days to two months ahead of the travel schedule depending on the season, requiring you also to have looked this up ahead of time (usually it’s earlier during chunyun). The images of harried migrants camping in snowy train station squares for hours or even days to wait for tickets have made the rounds in media inside and outside China, but there was no guarantee that even such zealousness could be rewarded with an available seat by the time you reached the ticket window. You had the option to book tickets over the phone, if you didn’t mind being put interminably on hold.

In 2010, Chinese railway authorities launched the official online ticket-booking website, 12306.cn, to improve the situation. But in practice, people found that this online system was full of technical bugs, like constant crashes and user-unfriendly interface, which made it no easier to buy a ticket online. Many even complained that booking a train ticket is just as hard as winning a lottery.

But for the enterprising businesspeople of the Middle Kingdom, where there is demand, there’s opportunity. Recently, some travel agencies and internet companies have begun to cash in on travelers’ desperation by establishing alternative online ticket-booking platforms that offer the same function as 12306.cn and more—if you pay the cost. Just type in “抢票(ticket-snatching)” in a search engine, and you can easily find tens of different ticket-booking sites, most of which claiming that for an extra fee, you can cut in front of the line and get better chances at a ticket than regular mortals. For those desperate ticket-hunters, it’s of course worth a try.

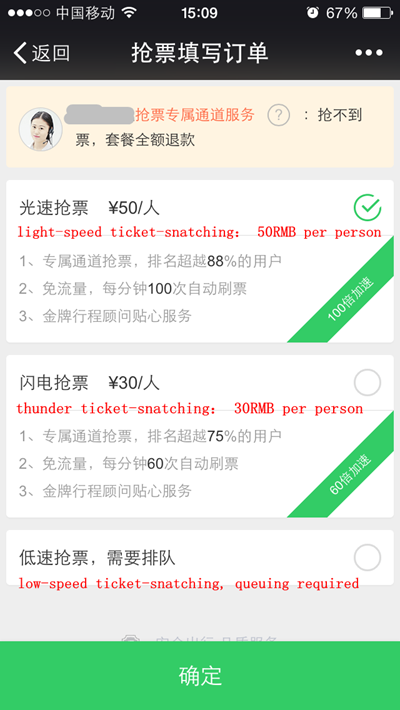

Guo Yipiao, a worker in Beijing from Henan, had been running the 12306.cn gauntlet for three days before she finally turned to the ticket-snatching software. “For three days in a row, I sat in front of my computer half an hour before the tickets were released and placed the order as fast as I could. But when I click to pay the bill, I was told that there were no tickets left,” Guo tells TWOC. Without any other choice, she decided to try an online ticket-snatching service. “There are different services at diffferent prices. You can choose to pay extra 30RMB or 50RMB. It seemed that, the more you pay, the more chances you get. I have no time, so I chose the 50 RMB one. And then, I actually got a ticket,” says Guo.

A screenshot of an online ticket-snatching platform

But not everyone can accept such a practice. Many portions of the public criticize that a pay-to-queue-jump model as unfair and even illegal. What has made the service more controversial is that in some cases, the online ticket-booking platform checks the “light-speed ticket-snatch” option by default and charges the user for the service without clearly informing them. Zhao Binghan, who works in Shanghai and tried to book a train ticket to her hometown Fushun, Liaoning, complained about this practice. Based on the recommendation of a colleague, Zhao turned to a ticket-snatching platform. After filling in all her personal information, she was required to prepay the ticket, and the price turned out to be 60 RMB higher than shown on 12306.cn. “It took me 10 minutes to figure out what happened. The system automatically checked the 50RMB ‘fast-snatching’ option and a 10RMB travel insurance package for me. The postion [of the text] and the font size were very inconspicuous. It’s like a bundle sale and I felt like I was scammed,” says Zhao.

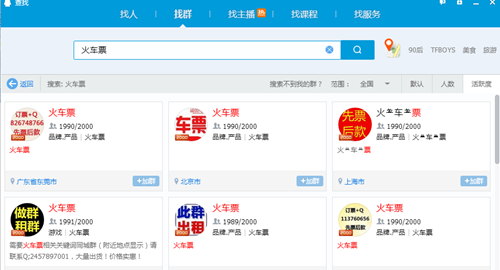

Many people were furious about such practices and said that it’s no different from ticket-scalping, which is illegal in China and was previously identified as a major reason for the dearth of train tickets in the Spring Festival rush. In 2012, the government adopted the nationwide “real-name train ticket” system under which each ticket must be printed with the rider’s real name and ID number, just to tackle the scalping problem. But five years later, ticket scalpers are still active and have even evolved into online business. Just search “train ticket” in QQ Groups, and hundreds of scalping groups will show up, claiming that they could snatch tickets on your behalf. And usually, if they sucessfully buy you tickets, you need to pay them tens to hundreds of kuai per ticket.

A list of QQ ticket-snatching groups

Some believe that those scalpers get tickets from railway insiders, while others say that they just hire people a large amount of people to scour the internet for tickets on a wide scale. TWOC contacted a scalper via WeChat in name of a client, and asked whether he could buy us a ticket from Beijing to Shenyang on the day before the Chinese New Year’s Eve. Though according to 12306.cn, there are no such tickets left, the scalper said they’d take care of it. The scalper told us that there are a few more tickets left to be released within in a few days, which could happen at any time of the day, and they had “professional” ticket-snatching software that could help book a ticket. Their rule is simple: there’s a 100 RMB per-ticket fee added to the ticket price, which you pay after the ticket is successfully booked. They even offered their software for sale: for 300 RMB, you can get access to the software until the end of this month.

Some others don’t want to rely on scalpers, and take matters into their own hands. Just search “ticket-snatching software” via Baidu, a list of plug-ins will be shown, most of which can be downloaded for free directly. In the past, many protested that these plug-ins created unfair competition, but no regulations against them have been issued. With these tools available everywhere online, there is no saying whether they work or not, due to a lack of a regulation and hence a lack of reliable statistics.

Some of the free ticket-snatching software you can find on the internet

Often travelers don’t have faith in these free products, and feel that a product you pay for might be more reliable. However, if you search the key words “train-ticket-snatching software” on e-commerce platform Taobao, the results page will tell you that “According to the relevant laws, the results cannot be displayed.” By putting some creative touches to your search, you can still find merchants selling those plug-ins, though their dubious legality should probably be a consideration before you want to put your money onto them.

If there is any useful lessons learned here for your ticket-hunting, maybe it’s just to keep a close eye on the ticket-release schedule, call on as many friends as possible to snatch together with you, click your mouse as quickly as you can (good internet connection is a plus), and most importantly, pray for good luck.

Cover image from pcjiaoyu.com