TV’s hottest anti-corruption drama includes scenes once thought forbidden

If you live in China but haven’t been watching In the Name of the People (《人民的名义》), you aren’t only missing out on a cultural phenomenon, you’re pretty much cut out of most water-cooler conversations. People of all ages and genders have been getting in on the anti-corruption drama, which has also been generating headlines.

Sponsored by the TV and Film Production Center under the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and screened by Hunan TV, the series takes the central government’s recent crackdown on corruption as its backdrop, featuring a hero named Hou Liangping who investigates cases involving corrupt officials in the fictional province of Handong.

The best American analogy is probably House of Cards. The first episode aired on March 28, and it attracted 2.41 percent of the total views, easily winning the ratings contest for that evening. The rating kept increasing as the story progressed, reaching as high as 3.91 percent in a single evening, more than twice the viewership numbers earned by the live broadcast of the World Cup qualifiers between the Chinese national team and Iran.

The show has also been performing well online. As of the time of writing this post, 38 out of 55 total episodes had been released and have received more than three billion views on iQiyi, one of the websites licensed to broadcast it. The episodes are coming out pretty fast, with two released every weekday.

It holds a rating of 8.5 out of 10 on Chinese media reviewing website Douban.

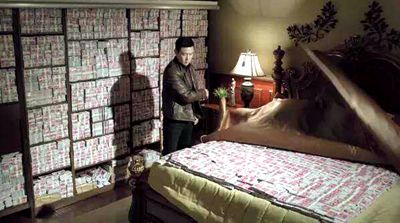

Since 2004, there haven’t been any shows based on corruption broadcast in prime time. But In the Name of the People has made a difference. It not only focuses on the corruption issue but also reveals many unsavory details of the Chinese political system. For example, in the opening of this show, a corrupt official was caught in his secret villa, with huge stacks of cash stuffed in fridges, closets and beds. Such a scene of visual impact is actually based on a real case. The prototype of the corrupt official in the show is Wei Pengyuan, former deputy head of the coal department at the National Energy Administration, who was sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in 2016 for corruption.

Other plot elements have also drawn inspiration from real cases. For example, one episode features a service window at the local Bureau for Letters and Visits from the Masses, which was so low that visitors had to bend over to talk to the officials, since there was no seat there. This seemingly small detail triggered plenty of feedback online. Netizens revealed that similar scenarios have taken place at the Social Security Office in Zhengzhou, Henan, and the police department in Zhuzhou Railway Station in Hunan province.

The service window from the show, from qq.com

Service window at the Social Security Office of Zhengzhou, from youth.cn

Service window at the Zhuzhou Railway Station, from sina.com.cn

Over the last decade, many topics have been discouraged on TV, but In the Name of the People has made a breakthrough. You can find many straightforward, candid lines in the show, which have rarely been seen on screen before. Here are some examples:

In the past, the public didn’t believe that the government could do bad; now they don’t believe the government could do good.

以前老百姓不相信政府会干坏事,现在老百姓不相信政府会干好事。

In the eyes of ordinary people, there is no uncorrupt official.

现在老百姓,对干部的感觉,就是无官不贪。

Frankly speaking, the quality of our officials is far lower than that of the average citizen.

坦率的说,我们的一些干部,其素质已经远低于一般国民素质了。

The important issue these days is not to educate the masses, but to educate the officials.

现在严重的问题,不是教育群众,而是教育干部。

You think people are toasting to how much they like him? They are toasting the power he holds in his hands.

你以为别人敬他酒敬的是他的人缘?那都是敬他手里的权力。

—Retired official: To serve the party, serve the people, that’s why we become officials.

—Official’s wife: Please. If others hear you say this, they will laugh to death. Who will believe you?

——为党为人民办事,这才是为官的目的!

——得了吧,这话你要出去说,得让人笑话死,谁信呐?

What’s wrong with our times? The ones who are upright and uncorrupt are the outcasts.

现在这是怎么了,清正廉洁,倒成了异类。

My family have been farmers for generations. I am the son of a farmer, and I am terrified by poverty.

我家祖祖辈辈是农民,我是农民的儿子,穷怕了。

The acting has also drawn praise, as the show brought together many veteran actors and actresses. In Chinese, they are called “老戏骨,” literally “old drama bones.” In today’s entertainment field dominated by “little fresh meat” (小鲜肉, cute young male actors, chosen more for their looks than acting skills) and “little flowers” (小花, young pretty actresses), it’s rare to find an ensemble cast as experienced as that of In the Name of the People, good acting skills no longer primarily brings fame or win ratings for the show. But to everyone’s surprise, these veteran “drama bones” won great popularity online and have even become favorites of young people. Netizens have even made many characters into memes found on social media and instant messaging platforms.

“Simmer down!”

“What else can I say?”

For those able to read Chinese, there’s also an online quiz that tells you (as it told the TWOC staff earlier today) which character from the show you are.

Of course, there are still many shortcomings in these show. Critics say it is slow-paced, much of the plot is driven by long, esoteric discussions, and the leading character’s presence isn’t commanding enough. But for Chinese audiences, who have been numbed by both schlock programming and safe subjects for so long, the bar has been vaulted over.

Cover Image from henan100.com

![[deahui.com]](https://cdn.theworldofchinese.com/media/images/5_3JVFmbn.width-800.jpg)