In a Beijing village, a community of strivers clings to a doomed existence

For Beijingers, this spring will likely be remembered as the season of the bricks.

The building of the Great Walls of Gentrification has blocked off—or knocked down—many of the city’s mom-and-pop businesses. Yet while progress marches on, the neighborhood of Huashiying (化石营, literally “Barracks of Fossils”), also known as Guandongdian (关东店) after the nearby thoroughfare, clings improbably to a precarious existence in the shadow of some of the city’s most iconic structures.

Despite an imminent demise reported as far back as 2008—when the government made the eradication of improvised buildings and makeshift utilities, known as “shed areas” (棚户区), an urban priority—this warren of shanties, shops, and local culture persists, wedged awkwardly near Beijing’s Eastern Third Ring and the gleaming steel and glass of the Central Business District (CBD).

And the survival of central Beijing’s last urban village seems even more impressive as the forces of modernity and order rip the heart from the hutong of Dongcheng and backstreets of Chaoyang. But for how long?

Only a few hundred meters across at its widest point, Huashiying is a throwback neighborhood, a window into a not-so-recent past when Beijing accommodated both monumental modern architecture and vibrant local neighborhoods. It is also the kind of organic community as equally reviled by overzealous urban planners in China as romanticized by visitors from afar.

It is an impromptu community of improvised buildings and makeshift utilities. Electric and cable lines crisscross overhead, connecting buildings with hastily rigged boxes which would defy code even in China. Water bladders, colored black to attract the sun’s heat, adorn rooftops, their nozzles dangling through windows and home-drilled apertures to provide at least a semblance of indoor plumbing and hot water to the building’s residents.

Small business, many of them unlicensed, serve the local migrant community

Occupied by the 3501 Clothing Factory the last 60 years, the neighborhood is ostensibly still home to its retired workers. However, almost all the rooms and shops are sublet to migrants from China’s interior. This is the turn-of-the-millennium Beijing that planners are working hard to eradicate: The Anhui auntie with the clothing store; the girls from Dongbei in the sketchy barbershop; the guy from Hebei and his fruit stand.

These neighborhoods, whether established in alleys or inside metropolitan blocks of a more recent vintage, have long been the first stop for rural workers seeking a better life in the capital. They were—and, to the extent allowed in today’s capital, still are—footholds for dreamers and the desperate alike to build a future in one of the most dynamic capitals in the world.

But those dreams grow in grime. As with the hutong neighborhoods of Beijing’s old inner city, life in Huashiying is one of privation. Public bathrooms are a throwback, and not in a pleasant way, to a time when restrooms looked like the scatological apocalypse of the Ragnarök, as imagined by Jackson Pollock.

Street-side vendors, increasingly rare in Beijing’s center, line the alleys, offering low-cost necessities for residents

Rows of old-world brick houses in the center, formerly the factory’s dormitories, function as anchors for the makeshift (and likely illegal) structures surrounding them. Inside, dark staircases wind past open doors. Swallows nest between floors, venturing out, like their human neighbors, in ever-expanding sorties to bring back life’s necessities. Huashiying is a convenient nesting spot, near enough to one of Beijing’s ever-increasing epicenters of prosperity yet tolerant of all, regardless of means. There are few quarters in downtown Beijing willing to allow nesting birds in the apartment hallways. The same could be said about affordable housing for the capital’s ever-fluctuating migrant population.

But life goes on. In the evening, the streets come alive; people wait until the last possible moment to return to dark and dreary rooms. Children play outside, dodging carts and bicycles. Men smoke and drink, green bottles emptied of cheap beer lying by their feet like fallen soldiers. Young women gossip in doorways, glancing furtively at male passers-by.

From above, one can see buildings crowded together in improbable geometries. A sign in the alley leading into the neighborhood warns of fumes from unsafe methods of heating; one fears what a single match might do. Amid the jumble, a lone tree rises from a roof, the surrounding shanties built tightly around the trunk, the roots burrowing into the foundation. China is famous for its “nail houses” (钉子户), lone holdouts against demolition, sticking up despite attempts to tear them down. The tree is a poignant metaphor for the whole block, a “nail tree” at the heart of a “nail neighborhood.”

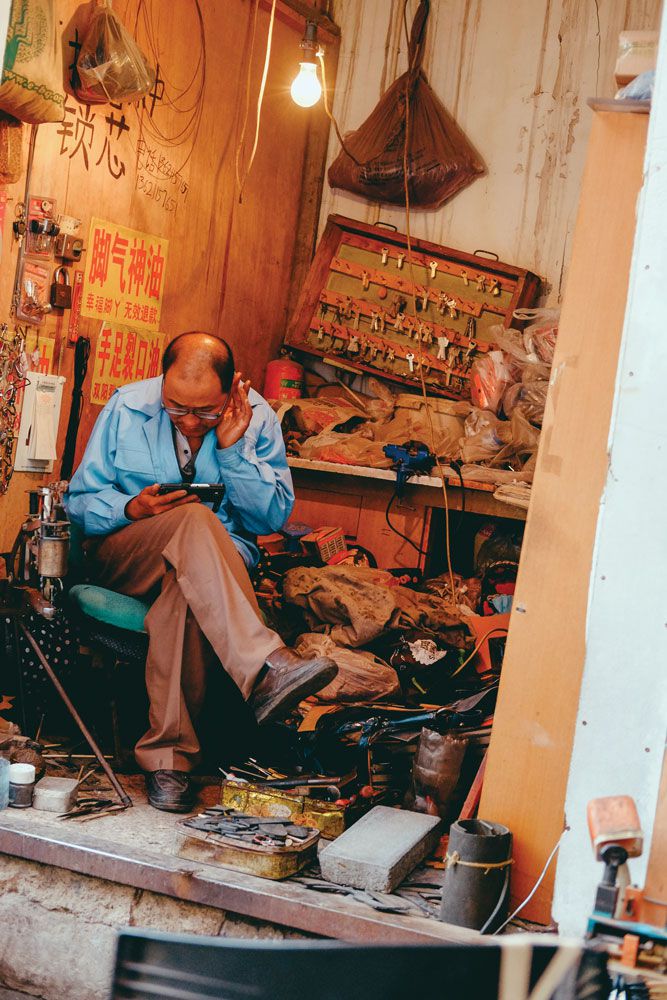

Ramshackle spaces offer affordable rents for local business, like this key-cutting and show-repair workshop

“There’s a rough quality,” says Jens Schott Knudsen, an attorney and photographer who has lived near Huashiying for five years. “But you get a sense that it’s a real community.” Knudsen’s photographs capture the stark contrasts of Beijing’s sometimes-haphazard development. “You have these shantytowns, and in the background is some of the most expensive real estate in the city.”

Beijing’s urban planners certainly have Huashiying in their crosshairs, yet it’s not entirely clear why nobody has pulled the trigger. Local scuttlebutt ranges from the area benefiting from the patronage (or at least the patience) of an influential landowner, to the neighborhood’s faintly preposterous reputation as a place for powerful men to quietly stash mistresses. A more likely explanation is that the land has simply become too expensive to develop.

Improvised storefronts are increasingly seen as an urban blight by city planners

The 0.01 square-kilometer CBD plot on which Beijing’s tallest skyscraper, the China Zun Tower, is currently nearing completion was purchased by the CITIC Group for an astonishing 6.3 billion RMB; that was in 2010. In 2016, China Real Estate News reported that “Century City,” a complex of shops, offices and high-end apartment, would be built over Huashiying.

Just untangling ownership could prove a lengthy obstacle. In 2011, developers sued disgruntled Tsinghua University faculty members who declined an offer of 2.4 billion RMB to vacate a campus in the CBD, even after the university approved the deal. The same year, new regulations on urban development banned expropriations unless they were for “the public good,” effectively making private projects like Century City illegal.

The community is home to many former factory workers who have lived there for decades

At one of Huashiying’s many cheap eateries, the staff speculate about the future. “So many of Beijing’s neighborhoods have been demolished,” says one. “Someday this will be too. But nobody knows when. It’s how it is in Beijing right now.”

Like their brick homes, Huashiying’s older residents are made of sturdier stuff. “We’re the original houses in the neighborhood—they want to move us, but they can’t afford it,” says Ms. Li, who lived in the neighbourhood for half a century. She has family all over the city, but doesn’t foresee herself leaving.

“Dongdaqiao [bus terminal] is right next to us, and I can go anywhere from here,” she says. “This wasn’t always so developed, but then they built the skyscrapers they covered us up—so we became the ‘ugly’ parts.”

Eventually, this heart of Beijing is expected to serve as the jewel at the center of Jing-Jin-Ji (京津冀), a centrally planned megalopolis which will combine the capital with the nearby city of Tianjin. The surrounding countryside of Hebei (the ‘Ji,’ after one of the province’s old names) will sprout communities intended to satisfy the residential, commercial, and industrial demands of the region.

Traditional-style roofs, increasing rare in Beijing, are surrounded by modern apartment blocks

In this vision of a well-regulated urban space—population 80 million or, to put it in other terms, Germany—Beijing’s city center will be a “political and cultural zone.” Nobody really knows what that means, and the municipal government is being vague on the particulars, perhaps deliberately so. But the mass campaign to brick up and over small businesses, many of which, to be fair, were operating without business licenses or in illegal spaces, suggests it will be, above all, an orderly city.

In the battle between organic—and possibly messy—local culture and the state’s relentless fetishization of a sanitized modernity, it seems depressingly clear that Beijing will indeed become a cleaner, more orderly and tidy, but altogether less interesting city.

A woman walks part a local relic—a scrapped Xiali model taxi cab

The denizens of Huashiying do not seem to worry much about forces beyond their control. Several said simply that they don’t know when they will be forced to move, but they’re expecting the worst.

“It’s hung on for so long,” says Knudsen, “But it’s hard to imagine where the city’s going now that it can possibly last much longer.” Until that time comes, this tiny urban village endures, an inconvenient reminder of Beijing’s diverse past, with little hope of inclusion in its brave new future.

‘It’s a Heartbreaking, Sad Place’—The Story Behind the Pictures

“It was hard to shoot because my subjects were guarded, even hostile, every time I raised my camera. It’s not hard to understand. If it were you wearing a cheap nightshirt and a pair of plastic slippers, taking out a chamber pot in the morning, would you want your photograph taken? Even those on the very edge of society have their dignity. I am not the most sharply dressed person, but once I entered the area, everyone was staring at me and my camera, knowing I wasn’t from the place, and probably someone on a novelty-seeking trip, who wants a peek into their lives.

“This urban village is beyond dirty and chaotic. It’s not even the kind of place a deliveryman or a low-level real estate agent would stay. The tenants are migrant workers drifting in the metropolis, taking on scattered small jobs, selling fake drugs, and running ‘black’ eateries on sewage-infested streets. You wouldn’t want to eat the stuffed pies and fried rice at these places. I was about to shoot a photo of the dishes, but the boss thought I was a journalist trying to expose them, and gathered people to watch my every move. I didn’t dare dwell for long.

“It’s a heartbreaking, sad place. I saw a migrant worker, after a day’s work, enter a dark workshop with 2 yuan in hand. He bought a big pancake so greasy it looked like it was pulled out of slop. He threw me a look that defeated all my courage. I couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter.”

Photography by Yu Birui (俞必睿)

Nail ‘Hood is a story from our issue, “Beyond Go.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.