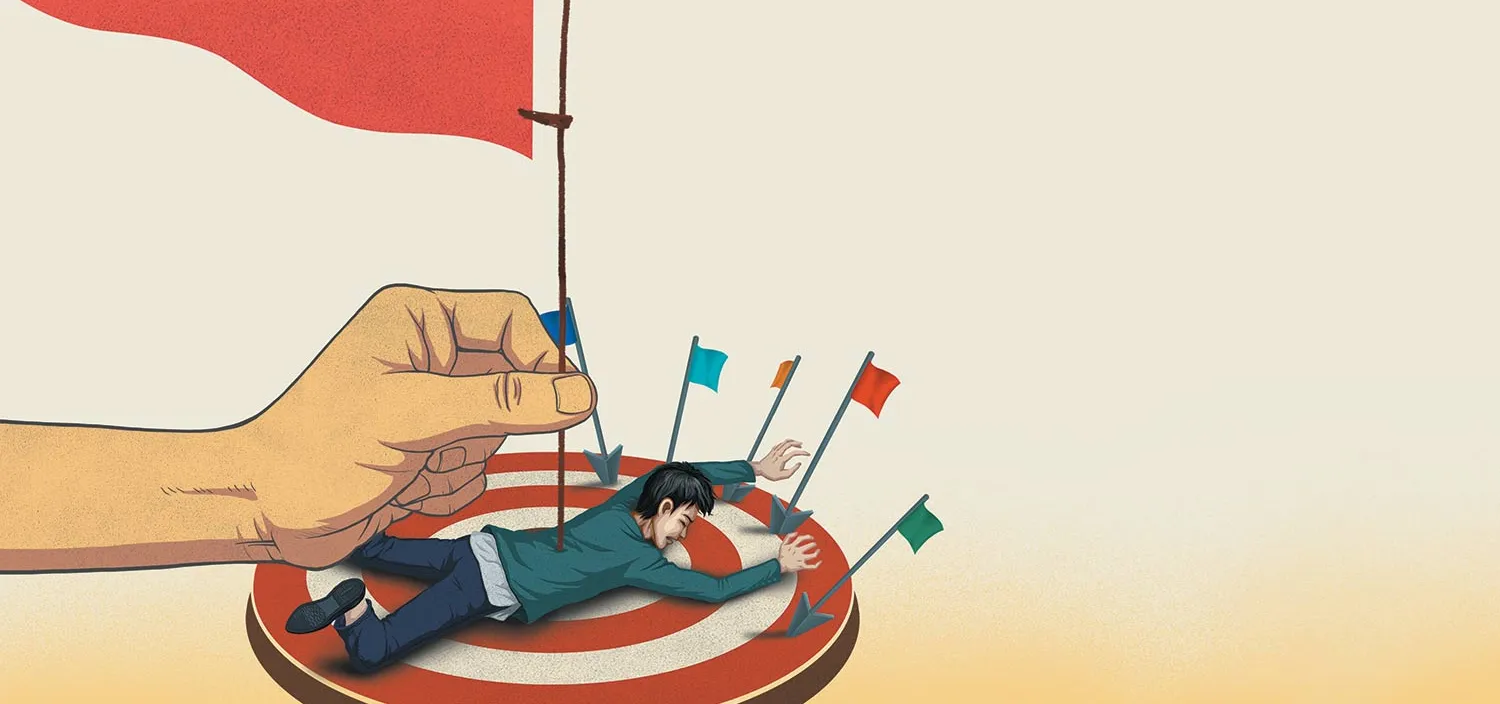

How flags are used to signify impending doom

We’ve all seen the war movies; Before heading off to battle, the rookie recruit kisses his girlfriend goodbye, promising, “As soon as I come back, I will marry you.” Or maybe he keeps a photo of that childhood sweetheart in his wallet to show others what’s waiting at home. It’s as bad as someone on Game of Thrones saying, “We’ll talk when I get back.”

They’re dead meat, we all know it.

Chinese moviegoers have a term for this sort of signaling: “Don’t raise a flag!” (不要立flag! Bùyào lì flag!) Originally a gaming term, “raise a flag” refers to particular lines or cues that serve as a sure sign of impending death or disaster. It usually exists as a half-Chinese, half-English term—立flag, with 立 (lì) meaning “raise” (mixed use of Chinese and English has become increasingly popular both online and in conversation among younger Chinese, even as some scholars and media have criticized the phenomenon, citing “language purity”).

This term is often used on social media or in “bullet subtitles” (弹幕 dànmù), viewers’ comments that shoot across the screen as chyrons when a video is played. Thanks to their overreliance on cliché, screenwriters make it easy for anyone to recognize a flag. When a hitman hero swears “This will be the last time I kill,” he is raising a flag—he’s guaranteed to not only kill many times more but probably die himself before washing his hands of this business; when a mother calls her child before surgery to reassure that “Mommy will be back soon,” that’s a flag that the she’s sure to die on the operating table; even a schoolgirl telling her best friend a secret after school raises a distinct flag that the consequences could be fatal. All the viewer can do is plead, “不要立flag!” or lament, “Flag 已立 (Flag yǐlì. The flag has been raised).”

You may have heard another expression—乌鸦嘴 (wūyāzuǐ, literally “crow mouth”) referring to someone who says something ominous. If one remarks of a person, “He has been out of contact for 24 hours. I’m afraid something has happened to him,” it’s crow mouth, and will be called out. But it’s more like a bizarro flag-raise, in which the meaning is totally inverted. When you hear some grim crow-mouth talk, it’s not regarded as ominous or unlucky. Instead, people call it “反 (fǎn) flag,” or “counter-flag,” meaning these phrases indicate that everything will, in all likelihood, turn out alright.

The logic goes that if one’s worst fears have already been aired, they are far less likely to transpire. It’s akin to jinxing: Just as pride comes before a fall, a declaration of confidence is like a red rag as far as fate is concerned. So better instead to predict one’s own impending doom as a way to ensure your own survival—a false-flag operation, if you will.

Not that flags are always life-or-death matters. In daily life, the criteria for what’s a flag and what flags mean are fairly loose. Indeed, having faith in just about anything could be interpreted as a flag. For example, your friend may casually predict sunny weather: “明天一定是个好天气。” (Míngtiān yīdìng shìgè hǎo tiānqì. It must be a good day tomorrow!) And you probably will say: “你最好别立flag,又雾霾了怎么办?” (Nǐ zuì hǎo bié lì flag, yòu wù máile zěnme bàn? You’d better not raise a flag! What if there’s smog again?)

It doesn’t matter how good the going is—even if you pass the day with flying colors, many Chinese think it’s safer to wave a white flag than raise a red one.

Red Flags is a story from our issue, “Beyond Go.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.