When civilizations collide over the stars, there is nothing left to do but declare battle…to the death!

Who knew that astronomy could be so dangerous?

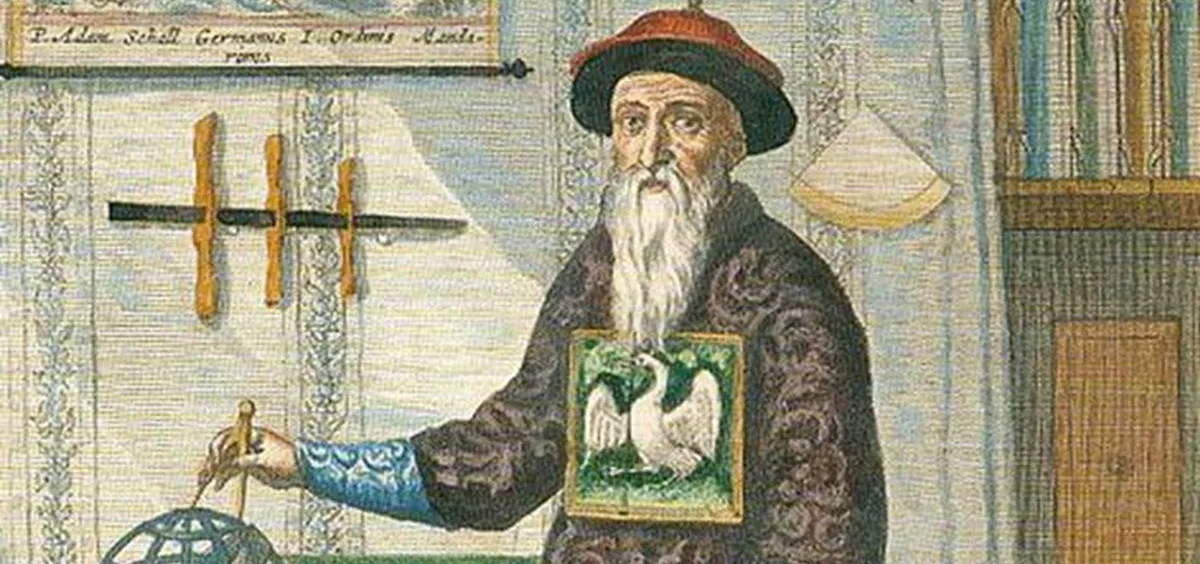

In the winter of 1668 to 1669, four European priests sat in a cold, prison cell in the imperial capital in Peking. The eldest, a German called Johann Adam Schall von Bell (汤若望), was unwell, having suffered a stroke after being sentenced to execution by slow slicing. His Flemish protégé, Ferdinand Verbiest (南怀仁), attended to the stricken Schall, while their two companions, Italian Jesuit Ludovico Buglio and Portuguese priest Gabriel de Magalhães, consoled themselves by writing letters they hoped would exonerate them and their Chinese colleagues, and spare them a gruesome fate.

For over 20 years, Schall had served as the Director of the Calendar Bureau—ever since he had refused to flee the capital during the Manchu invasion. Schall had updated an imperial calendar, which had not seen major revision in over 250 years, impressing the new Qing regent Dorgon (多尔衮) with his mathematical prowess. Over time, Schall became a favorite of Dorgon’s nephew, the young Shunzhi Emperor (顺治皇帝), who saw Schall as both teacher and friend, bestowing imperial titles and ranks on the foreign missionary and even, according to some sources, referring to Schall affectionately as “Grandpa.”

But the Shunzhi Emperor died of smallpox in 1661. His son, the Kangxi Emperor (康熙皇帝), was still only a boy and his regent, Oboi (鳌拜), dominated the court much as Dorgon had done in Shunzhi’s early years. Oboi was suspicious of Schall’s influence and sympathetic to officials who were concerned about having a foreigner in charge of something as important as the calendar. Sure, Schall was good with mathematical tricks, but how could he understand the ritual and cultural significance of auspicious dates for important events like weddings and funerals? Moreover, Schall and his assistants were Christians.

Schall also had his own troll: Yang Guangxian (杨光先), who was a scholar of sorts, a former guardsman and self-taught astrologer with aspirations of serving at the Qing court. He wrote several memorials to the throne accusing Schall of high treason, of being the leader of a heterodox cult, and of making critical errors in selecting auspicious dates. Yang and his supporters charged that Schall had chosen an inauspicious occasion for the burial of an infant prince who had died in 1658. This lapse in astronomical judgment was then blamed for the untimely death, two years later, of the child’s mother, the Consort Donggo, who had been a favorite of the Shunzhi Emperor.

In November 1664, Oboi ordered Schall removed from his post, stripped of all titles, and imprisoned, along with his three fellow Jesuits and their staff, to await execution. After a lengthy winter incarceration, the court took mercy and commuted their punishment to banishment. Oboi, in the market for a new astronomical bureau chief, appointed Yang Guangxian to take the place of the disgraced Schall, who died soon after.

But it didn’t take long for Yang’s incompetence to catch up with him. In 1667, Yang brought back a flawed traditional calendar for what would be the Roman year 1668 and made revisions that even the 13-year-old Kangxi Emperor could see were a bit off. The Emperor defied Oboi, and invited Verbiest, Schall’s principal assistant, to the court to inspect the calendar. The Kangxi Emperor subjected Verbiest and Yang to a series of tests over who could produce the most accurate calendar for the coming year. Ultimately, Verbiest’s calculations were chosen and promulgated throughout the empire. Yang was removed from office and condemned to face his own grisly execution. Eventually, the emperor settled for dismissing Yang and sending him home in disgrace, though he died enroute.

Verbiest was appointed to the Calendar Bureau, although at a lower rank than Schall once held, continuing a tradition of Jesuit astronomers serving the Qing court that would last until 1805.

Astronomy Domine is a story from our issue, “Fast Forward.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.