The sharing economy takes on China’s fitness industry, amid concerns over gym memberships and reliability

Gyms are increasingly common in Chinese cities, even though membership penetration remains low (around 5 percent in first-tier cities) and trust even lower, with fly-by-night operations frequently absconding with clients’ fees.

The latest development in the sharing economy, “exercise pods” and “mini gyms,” is hoping to change all of that.

Companies such as ParkBox, Ximo Panda, Sunpig, and Misspao offer temperature-controlled pods, or small rooms with exercise equipment, which can be booked via app at a low price. The pay-as-you-go model is particularly attractive to middle class, cost-conscious millennials, as is the ability to track one’s exercise data on the company’s app.

For customers like Ms. Chen, a finance professional in her early 30s, an alternative to the membership model is likely to be welcomed. With her yoga studio closed for renovations, its members “have no idea when, or even if, it will open again.” Fearing the closure may be permanent, Chen fpurchased an expensive membership at another studio to maintain her regimented workout (she hopes fellow yogis will use her card and pay her back).

From having 500 fitness centers in 2001 to over 26,000 today, China’s gym sector is expanding, even as clients like Chen are being turned off by their service. Lou Zhang, whose company helps train gym managers, thinks Chen’s cynicism on gyms is warranted: “It’s about fast cash. There’s a lot of copying being done, and 80 percent of investments fail. That’s very bad for the reputation of the fitness industry.”

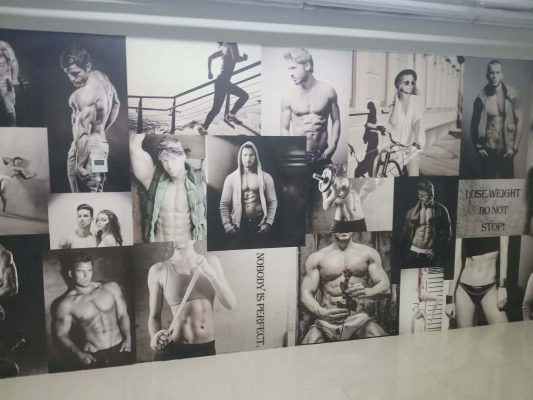

Stock photos and motivational quotes at a typical Chinese gym

Closures are particularly controversial, because members are required to purchase a year-long membership upfront (or more years at a steep discount), or a 100-visit or 100-class card—money that is rarely, if ever returned. “I really want to join a gym,” says Mei, a government employee in her late 20s, “but I am worried that I cannot afford it. My colleague recently purchased a two-year gym membership for her family, but it was 10,000 RMB – higher than our monthly salary!”

Those who do cough up for a membership may find unanticipated disruptions; it is not unheard-of for small gyms to close for an entire month for Spring Festival.

Additionally, many members feel pressured by staff to purchase additional services, like personal training. As Li Yi, a 23-year-old from Wuhan, told the Straits Times: “I had bad experiences at traditional gyms where fitness coaches are more like salesmen.” Li anticipates that she can save upwards of 2,000 RMB per year forgoing the traditional membership and doing her workout in an “exercise pods.”

Even budget gyms require a membership, paid upfront

Huang Xiaolei, CEO of Shanghai-based ParkBox, claims that the exercise pod industry has enormous potential. Even though members pay just 10RMB per hour, a ParkBox is said to become profitable more quickly (within an estimated six to eight months) than a traditional gym, due to low overheads. However, there are challenges: Misspao (essentially a treadmill in a cubicle with air con, purifier, and mini-television) already has a 100 million RMB valuation, but potential users still worry about hygiene, privacy, and equipment damage.

Perhaps the greatest signal of industry challenges ahead is the example of one of the early leaders in the “exercise pod” space, Shenzhen-based Supermonkey. Founded in 2014, the company has already pivoted away from its original model and, according to EJInsight, now “has three revenue sources: running group class studios, selling gymboxes to property developers, and operating staffless gym rooms.”

New fitness start-ups often go for a more modern look

The appearance of Supermonkey’s pay-as-you-go group class studios may have a wider impact than the “exercise pods” themselves. A one-hour class is normally about 70 RMB and led by trained fitness coaches in yoga, kickboxing, weightlifting, Zumba, or even mini-trampoline jumping. (By comparison, even with the studio card, Chen’s yoga classes cost upwards of 100 RMB.)

Pay-as-you-go classes are becoming an international trend: In 2018, the South China Morning Post credited them as reviving the fitness industry in Hong Kong. A quick stroll through Beijing’s Sanlitun or CBD area will see a proliferation of established, small gyms offering such classes. They hope that this new strategy will attract those in the middle and upper class who have forgone costly memberships, such as Kerry Sports’ 25,000 RMB yearly fee.

What is yet to be seen is if these new exercise trends will actually get more Chinese moving, or if they simply offer more options to those who already make exercise part of their weekly routine. Regardless, with Supermonkey finalizing 360 million RMB round of funding earlier this week for further expansion, these trends are unlikely to fizzle out any time soon.

The author at a “pay-as-you-go” fitness class

Cover image from PxHere

Other photos provided by Emily Conrad