How will the first all-Chinese title fight in UFC history impact China’s MMA community?

It’s early and bitterly cold, but the park next to Xi’an’s city wall is alive with activity. A group of men chat in between sets of muscle-ups on exercise bars. Elderly women walk side by side, clapping their gloved hands, while joggers cut a path through it all, leaving trails of icy breath.

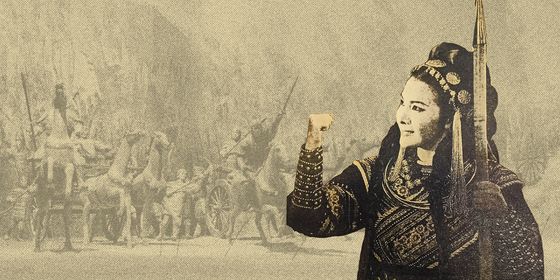

But there is one noise that dominates the soundscape: the periodic “Ha!” of young, eager voices. Rows of children, eight deep, fight imaginary opponents in their martial arts class.

During a break, I show a group of girls pictures of famous athletes. Puzzled faces greet a photo of Lionel Messi. Cristiano Ronaldo gets a response: “He’s a basketball player. I know. My brother told me,” a rosy-cheeked young girl says confidently.

Then, I show them a picture of a strong, shorthaired Chinese woman. “Ah, Zhang Weili, Zhang Weili,” they chant. Despite training in traditional martial arts, the girls’ hero is not some old-school kung fu fighter, but China’s first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) World Champion.

On April 3 in Las Vegas, Zhang Weili will defend her title against Yan Xiaonan in the first all-Chinese title fight in UFC history. The UFC, the world’s premier mixed martial arts (MMA) organization, has evolved from putting on what was once labeled by US Senator John McCain in 1996 as “human cockfighting” to a professional sport with global popularity. That popularity now extends to China, and even to young girls practicing martial arts in the park.

Strength to strength

Liu Chen greets me at the entrance to Sharky’s, a popular Xi’an sports bar. A strong stocky fellow and accountant by trade, the 28-year-old has the beginnings of cauliflower ear from years of learning Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. Liu spends his spare time organizing UFC watch parties at local bars and restaurants.

Liu says the popularity of UFC has grown since 2020. “Ever since Zhang Weili fought Joanna [Jedrzejczyk], MMA went from being kind of unknown to kind of popular. It’s not on the same level as, like, football, and definitely not basketball, but people know the big fighters, like Zhang, Yan, and Song [Yadong].”

In March 2020, Zhang defended her title against Polish fighter Joanna Jedrzejczyk in what has since been recognized as one of the greatest fights of all time. Zhang and Jedrzejczyk traded ferocious punches and kicks for five rounds, breaking several records in the process, with Zhang eventually winning a split decision. But the lasting memory for the Chinese fans was Zhang getting her hand raised next to a disfigured Jedrzejczyk, who suffered a hematoma on her head causing it to swell up.

Before the fight, Jedrzejczyk posted a photo of her standing next to Zhang while wearing a gas mask, apparently mocking the ongoing Covid-19 outbreak, which was in its infancy at the time. The fight not only made Zhang a champion, but a hero in the eyes of fans.

“The country was suffering during Covid; most people were quarantined and there was a lot of anti-China news across the world. It was a satisfying win. She defended our honor,” Liu tells me.

Liu says if that fight had happened post-pandemic, the influence would have been even bigger. “The social media buzz around that fight was huge because everyone was at home. But that also meant people didn’t go and sign up at their local gym or start going with their friends to watch the fights together. Zhang Weili became popular but MMA in general, not so much.”

Liu says many bars are still hesitant to put on events for UFC matches which, due to the time difference between China and the US (where most matches take place), are often on Sunday mornings. Many bars still consider the sport niche and only air big fights like the upcoming bout between Zhang and Yan.

But according to Liu, the main reason Chinese MMA still lags behind America and Brazil, despite the domestic athletic talent and interest in martial arts, is the lack of quality sparring partners in the country. ”Most kids in China learn kung fu. They see it on TV, in wuxia books and comics and think it’s cool. It doesn’t work on the street or in the octagon [MMA rings are generally octagonal].”

Liu and many other MMA practitioners believe traditional Chinese martial arts are impractical for real-world self-defense scenarios. This argument has been bolstered by a series of incidents where modern MMA practitioners fought, and sometimes brutally defeated, traditional martial arts masters. In 2017, professional MMA fighter Xu Xiaodong went viral for beating a Tai Chi master in seconds.

Perhaps that’s why despite high levels of martial arts participation in China, of the 610 fighters on the UFC roster, only 12 are Chinese, with the list dominated by American and Brazilian fighters. And of all the martial arts elements absorbed into modern MMA, traditional Chinese martial arts techniques are nowhere to be seen.

“Sanda [a form of Chinese kickboxing with grappling elements] is pretty effective, but on its own—isn’t enough. That’s why Chinese fighters who get to a certain level go and train abroad,” Liu says. Zhang and Yan both currently train outside of China.

The Zhang effect

Away from the icy cold, behind steamy windows in Xi’an’s high-tech Gaoxin district, dozens of predominantly white-collar workers come to DT Boxing to train in boxing, kickboxing, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. The pitter-patter of feet running around on the mats during warm-up makes way to the thump of the coach demonstrating a kick on the heavy bag. Ming Hao, the 33-year-old owner of the gym, is sitting behind the front desk. Originally from Liaoning province, Ming is a tall, muscular figure, and with his goatee, wouldn’t look out of place in an ’80s Hong Kong action movie. Ming trained with one of the two fighters in the UFC 300 title fight, Yan Xiaonan at Xi’an Sports University.

I’m struck by the makeup of the class: almost equally split between men and women, a far cry from the predominantly male gyms I am used to in my native Scotland. “Fighters like Zhang have definitely increased the popularity of MMA amongst women,” Ming tells me. “But most fighters seeking to fight professionally are still male. Women who come to my gym see Zhang Weili and think: ‘I want to look like that,’ not ‘I want to get hit in the head.’ At least that’s the current attitude.”

Ming has also noticed MMA’s popularity growing in recent years. ”It’s not just because of Zhang Weili, but because many superstars nowadays are training in boxing, Muay Thai, and MMA. Even rappers are writing songs about MMA fighters and more young people are into hip hop than martial arts.”

On social media platforms like Weibo or Xiaohongshu, a search for MMA or kickboxing brings up as many interviews with celebrities discussing training routines or filming fight scenes for movies as they do action from professional UFC fights or interviews with fighters.

UFC fans in China are often attracted to individuals rather than the sport itself. Ming believes the fight between Zhang and Yan won’t increase MMA’s popularity as much as the growth of the individual fighters’ brands. “Martial arts is different to football and basketball. Most regular people don’t participate,” he says. Instead, “People pay attention to fighters they care about, and in turn fighters know to become famous, the UFC is the best place for them,” which attracts more people to participate.

Tomorrow’s champions

Back in the park by Xi’an’s city wall, the girls bow to their martial arts instructor, signaling the end of the class, and head toward the queue of waiting parents’ cars.

One girl comes over to me, encouraged by her watching parents, to chat about Zhang Weili. I ask her why she likes China’s first UFC world champion. “Zhang is cool and strong and doesn’t need a husband to buy her a house or a car,” she says. With the biggest fight in Chinese UFC history just around the corner, MMA fans will hope many more children will be inspired to become champions like Zhang in the future.