From “stroking fish” to “buying soy sauce,” TWOC presents slang for slacking

Insomnia, baldness, and death by exhaustion: Chinese professionals have been vocal recently about the consequences of overwork in their country.

But not all “corporate cattle” penned up in offices are actually pulling their weight. According to Gallup’s 2013 “State of the Global Workplace” report, only 6 percent of employees in Chinese companies were “engaged” in their tasks at work at any given time.

In workplaces, colleagues who appear to put in long hours at their desks, but are in reality surfing the web or shopping online, are said to be 摸鱼 (mōyú, “fishing,” literally “stroking the fish”). This term derives from the idiom 浑水摸鱼 (húnshuǐ-mōyú, fishing in murky waters), which refers to taking advantage of a confusion to advance their own interests.

Not all shirking is voluntary. Employees may feel obliged to prove their industry by working late even if they’ve finished all their tasks. A debate over this practice, dubbed “被迫摸鱼式加班” (bèipò mōyúshì jiābān, “forced overtime fishing”), received over 23,000 comments on Weibo in August. One user declared:

Our manager often works overtime and dislikes those who leave before him, so we have no choice but to fish after hours.

Jīnglǐ jīngcháng jiābān, yě bù xǐhuan zǎo xiàbān de rén, wǒmen zhǐhǎo mōyúshì jiābān.

经理经常加班,也不喜欢早下班的人,我们只好摸鱼式加班。

The term can be used to cheekily express one’s own disinclination to work:

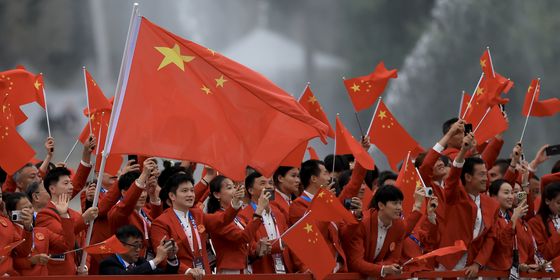

Tomorrow is National Day. I’ll just “fish” until we’re off for the holidays.

Míngtiān jiùshì Guóqìngjié le, jīntiān mōyú děng fàngjià.

明天就是国庆节了,今天摸鱼等放假。

Laziness may be human nature, as partially evidenced in the ancient origin of another term for slacking off: 划水 (huáshuǐ, “paddling water”). It originally described boatmen who would half-heartedly splash their oars from side to side while their colleagues did the actual rowing. It was picked up by players of World of Warcraft to refer to underperforming teammates, and then expanded to the realms of work and study.

Fans may use the term to deride the members of a sports team or musical group they dislike:

That band member forgot all her dance moves. She is definitely slacking.

Nàge nǚtuán chéngyuán wǔdǎo dòngzuò dōu wàng le, míngxiǎn shì zài huáshuǐ.

那个女团成员舞蹈动作都忘了,明显是在划水。

A third term for those not engaged in their tasks, 打酱油 (dǎ jiàngyóu, “buying soy sauce”), originated in 2008 when a TV journalist approached a middle-aged man in the street for a comment on singer Edison Chen’s nude photo scandal. “关我什么事?我出来打酱油的。(Guān wǒ shénme shì? Wǒ chūlái dǎ jiàngyóu de. What’s it got to do with me? I just came out to buy soy sauce),” the apathetic citizen replied.

This expression is also used to show humility:

I won’t take any responsibility in this project. I’m just in it for experience.

Wǒ zài zhège xiàngmù li bú fùzé shénme, jiùshì lái dǎ jiàngyóu de.

我在这个项目里不负责什么,就是来打酱油的。

From ancient boat convoys to Fortune 500 companies, no organization is safe from shirking; that is, until a deadline looms, and the boss requires all hands on desk to fix mistakes—by working overtime.

Shirking 9 to 5 is a story from our issue, “Tuning Up.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.