Covid-19 has led to a boom in medical apps and remote health consultations, but will it last?

With millions of Chinese pushed into the shelter of their own homes in recent months by the coronavirus outbreak, going out to see a doctor or pick up medicine suddenly became impossible, or at least perceived as risky.

Faced with such difficulties, and increasingly anxious that they may have contracted Covid-19 themselves, thousands have flocked to medical apps and websites to get their care remotely.

Now, with life across the country slowly returning to normal, the companies behind these services are hoping the boom in online healthcare will continue. But underlying issues such as a lack of trust, patchy regulations, and privacy concerns spell an uncertain future for the market.

Online healthcare platforms, which began to emerge in China around five years ago, typically monitor the health data of users and offer consultations with doctors through video chat. They often link poorly equipped rural clinics to urban doctors, and even use AI to diagnose diseases.

User numbers, though, have soared in 2020, with anxiety linked to Covid-19 a core part of the increased demand—on Weibo, the hashtag “What to do if I always suspect I’ve got the virus” has been viewed 570 million times.

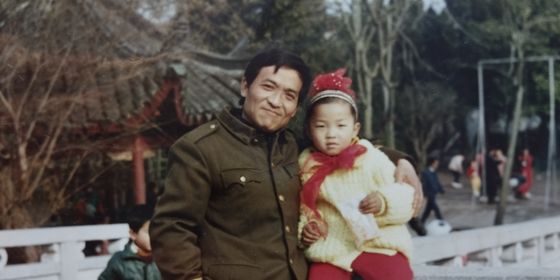

Long lines at hospitals, which increases the risk for cross-infection, make online health platforms attractive during the Covid-19 epidemic

Ping An Good Doctor, a telemedicine app founded in 2014, claimed in mid-February that it had recorded 1.1 billion visits to its platform since the outbreak, and that new user registrations had increased by 1,000 percent. According to CCTV, from January 22 to February 25, doctors on Ping An gave over 4.26 million online consultations, of which 25 percent were related to Covid-19; there were 20,000 doctors on average giving consultations daily.

JD Health, a similar platform, claimed that monthly consultations increased tenfold since the outbreak and that it was seeing 100,000 online consultations per day in February, with the largest number from Wuhan. Alihealth, owned by e-commerce firm Alibaba, set up a free “online clinic” for those in the hard hit Hubei province, allowing users to buy and receive medicine without venturing outdoors.

Dingxiang Doctor, an online health information platform, set up a “Coronavirus Emergency Group” just a few hours after it was announced on January 21 that human-to-human transmission of the virus had been confirmed. Its tracking map for coronavirus infection numbers and locations had been viewed 2.5 billion times as of the beginning of March, according to the Economist, and the platform had 15,000 doctors working during the outbreak to offer online consultations and suggestions for treatment.

China’s telemedicine market had been growing steadily before the recent boom. Seen as a solution to the uneven distribution of China’s healthcare services, which causes patients to flock to highly-rated urban hospitals even for minor ailments, the remote healthcare industry was estimated to be worth around 49 billion RMB (6.9 billion USD) in 2019.

But the virus has accelerated growth: the market is expected to hit 100 billion RMB (14 billion USD) this year and 200 billion RMB (28 billion USD) by 2026, according to 36Kr, a technology news website. The stock price of Ping An Good Doctor has surged 33 percent from this time last year, while Alihealth’s have risen an even more impressive 58 percent, even as the rest of China’s economy slumps due to the outbreak.

It’s not only private companies that have gotten in on the act: public hospitals and local governments are also using technology to reach patients. A hospital in Wei’an, Jiangsu province, set up an “online clinic” to alleviate the normally large lines seen at the hospital, which could potentially lead to cross-infections. Patients who suspect they have Covid-19 can have their symptoms checked out online, get medicine prescribed, and find out whether they need to come to the hospital for treatment.

On January 31, a patient was diagnosed as negative for Covid-19 by doctors in Guizhou by a remote consultation over a distance of 295 kilometers. In Hefei, Anhui province, a “Remote Image Healthcare Platform” has screened nearly 90,000 X-rays for the virus. Government-backed and volunteer organizations have also offered mental health consultations by telephone and online.

But getting the public to trust online medical care remains a challenge, and regulations are needed to ensure that doctors working on these platforms provide the best care. Dr. Zhang Qu, a pediatrician in Zhejiang province who works part-time for an online healthcare platform, told 36Kr that doctors cannot give a diagnosis online, “just a few treatment suggestions,” as Chinese regulations limit online medical services to follow-up consultations and prescriptions, and don’t allow first-time diagnosis. Platforms have only been authorized to sell prescription drugs since 2018.

A “5G remote healthcare” system on display at a technology fair in Wuhan in 2019

In most of the country, health insurance doesn’t cover online medical expenses at present, another barrier to the potential of these services, though some provinces have lifted this restriction in response to the virus outbreak. The privacy of users’ sensitive health data remains a problem, too, in the absence of industry standards for keeping online information secure—according to Dr. Zhang, many of his recent patients are worried about being forced into quarantine if local residential committees find out they have a fever, and he is frequently asked whether online consultations are recorded.

The SARS outbreak in 2003 is seen as the start of China’s e-commerce revolution, which is now an essential part of life for millions in the country. It remains to be seen if 2020’s public health emergency will bring the same long-term boost to online care.

All images from VCG