Banned books throughout Chinese history

Books, music, social media posts, even memes: nothing is safe from China’s modern system of censorship, perhaps the most comprehensive ever known.

But long before censors began removing errant WeChat stickers (or memes that compare politicians to cartoon characters—we’re looking at you, Winnie) China already had a long history of banning written works deemed undesirable by officials. The English bard Shakespeare had his work banned, along with just about everything else foreign, during the Cultural Revolution, only to come roaring back into fashion in the decades since, while the works of Ming dynasty poet Qu You were considered far too lurid and scandalous to be acceptable during his time.

From alleged book burning during the Qin dynasty, to the banning of works in the (allegedly more open) 1980s, TWOC introduces five books banned throughout China’s history:

Lu Ban Shu《鲁班书》

(JD.com)

This two-volume book was written during the Spring and Autumn period (771 — 476 BCE) by Gongsun Shu, a renowned architect of the time, under the name Lu Ban. In the first volume, Shu detailed his architectural theories, but in the second, much more controversial part, he delved into the world of gods, spirits, and rituals.

Shu outlined various incantations and curses which were considered black magic by the ancient censors, and the book’s circulation was restricted to prevent the public engaging in witchcraft, and perhaps even using the book’s spells to threaten rulers. The book also featured writings on Daoist “magic” and suggestions for medical treatment. It was said that whoever read through the entire second volume would be cursed to live alone, become widowed, or be made disabled. To date, the original manuscripts remain lost, probably hidden away or destroyed by successive rulers of past dynasties afraid of what might befall them should such witchcraft become common knowledge.

Guiguzi 《鬼谷子》

(JD.com)

The ancient writer Wang Xu, a hermit who lived in what was known as the Ghost Valley more than 2,000 years ago, is credited with writing what became one of the most controversial works in the Chinese philosophical tradition during the Han dynasty (206 BCE — 220 CE). The book advocated the notion that humans are by nature wicked, in direct contrast with the orthodox Confucian view that people are all “kind at birth.” That suggestion was so anathema to official doctrine at the time that the book was banned during the western Han period (206 BCE — 24 CE) when Emperor Wu officially instituted Confucianism as the thought system of imperial rule.

The Guiguzi, which is likely to have been the work of several scholars over many years, discusses strategies for political lobbying, power brokering, and military conquest. The chapter on “opening and closing the gate (捭阖),” for example, speaks of the art of building political coalitions. Despite the ban, the book was influential, and students of the philosophical tradition it outlined continued to refer to and adapt many of its theories throughout histoy. Sun Bin, a well-known military strategist and perhaps a descendant of Sun Tzu, who is credited with writing The Art of War, was one alleged student of Wang Xu.

New Stories Told While Trimming the Wick 《剪灯新话》

(JD.com)

Ming dynasty (1368 — 1644) poet Qu You has been credited with producing the first book to be officially banned by a Chinese government. Qu’s work, New Stories Told While Trimming the Wick, caused consternation at the imperial court with its sexual themes, and subtle criticisms of society under Ming rule. In the book, Qu described sexual encounters between humans and spirits, and the sex lives of the lower classes; both subjects were considered taboo. In one section, Qu wrote about the intimate relationship between a man and a female ghoul.

Copies of the book were burned and buried by the Ming imperial court. But despite the drastic measures at the time, the book became popular elsewhere in east Asia, particularly in Korea, where classical Chinese was still used and understood by scholars and officials. Qu’s New Stories inspired what is widely regarded as the first novel of Korean literature, Tales of Mount Geumo (金鳌新话), which was written in classical Chinese by Korean author Kim Si-Seup in the 15th century.

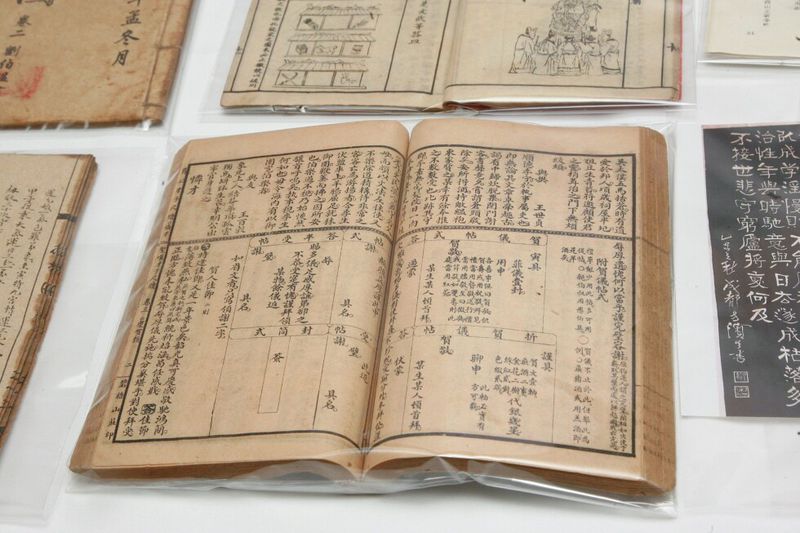

Tui Bei Tu 《推背图》

(VCG)

This book of prophecies earned its name from a story about the writers Li Chunfeng and Yuan Tiangang, two Chinese scholars who also claimed to be seers, in which Yuan pushed Li in the back to warn him that he had revealed too much about the future. Published during the Tang dynasty (618 — 906), the Tui Bei Tu includes 60 xiang (divinatory symbol) drawings that are meant to predict the future rise, fall, tranquility, and turbulence of China from the Tang up to the year 2043.

Of these 60 prophecies, perhaps 55 may have already come true, including the prediction of the ascendance of China’s first, and only, empress, Wu Zetian. Following the Tang, subsequent emperors prohibited the book’s publication for fear that it might disturb the minds of the people and lead them to revolt. Many other rulers simply changed the contents to reflect better on themselves; during the Song dynasty (960 — 1279), hundreds of versions were fabricated by Emperor Taizu. The version that remains today was composed by Jin Shengtan, a critic during the Qing dynasty, and the manuscript is currently on display at the National Palace Museum in Beijing.

The Ugly Chinese《丑陋的中国人》

(JD.com)

“You are sick. You need help,” Bo Yang wrote in this collection published in 1986. The Ugly Chinese is a highly critical compilation of lectures and articles by Bo that offered a fierce attack on Chinese culture and the Chinese character during a period when space for critical works opened after the Cultural Revolution.

Bo, writing in Taiwan, and his critique had shades of Lu Xun, blaming the ills of society on the nature of Chinese culture, often using satire and acerbic wit. “Chinese people are highly reluctant to admit their errors, and can produce a myriad of reasons to cover their mistakes. There’s an old adage: ‘Contemplate your faults behind closed doors.’ Whose faults? The guy’s next door, of course!” he wrote.

The unflattering title and contents were understandably controversial and provoked huge debate on the Chinese mainland, with some seeing it as an unwarranted attack on Chinese cultural heritage. Together with the similarly critical TV documentary, River Elegy 《河殇》(itself eventually banned), The Ugly Chinese was symbolic of a deeply reflective and critical period for Chinese media during the 1980s. Bo’s works were banned by the Chinese government in 1987, but many bootleg copies of The Ugly Chinese continued to circulate. Only since 2004 has the Chinese government reissued selections of his writings.

Cover image from NeedPix