A Malaysian-Chinese doctor pioneered modern epidemic control during the deadly Manchurian Plague of 1910

December 24, 1910 was a special Christmas Eve for Dr. Wu Lien-Teh (伍连德). Arriving in Harbin by train with a microscope in his luggage, the Malaysia-born, Cambridge-educated epidemiologist, whose ancestors hailed from Guangdong province, had come to northeastern China to fight a life-threatening disease.

Two months prior, at an inn in the frontier town of Manzhouli, a pair of fur traders who had returned from Russia suddenly vomited blood and died. Within 10 days, the disease reached Harbin, and from there, traveled across the northeast on the new railroad the Qing dynasty had finished with Russian assistance just seven years before.

The epidemic ravaged all three northeastern provinces—Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning—putting millions of lives at risk. Harbin saw over 50 deaths daily on average; 183 people died on one particularly fatal day. The town of Fujiadian, now Harbin’s Daowai district, was hardest hit due to poor sanitary conditions and a dense population. Those known or suspected to have been in contact with the sick were quarantined, but no effective treatment was available.

Both Japan and Russia were on the ground trying to combat the epidemic, while also vying for control of China’s northeast. For the waning Qing dynasty, a failure to contain the outbreak would cement these foreign powers’ claims over its territory. The 32-year-old Wu, then working at a medical school in Tianjin, was invited by the Qing government to lead their anti-plague efforts.

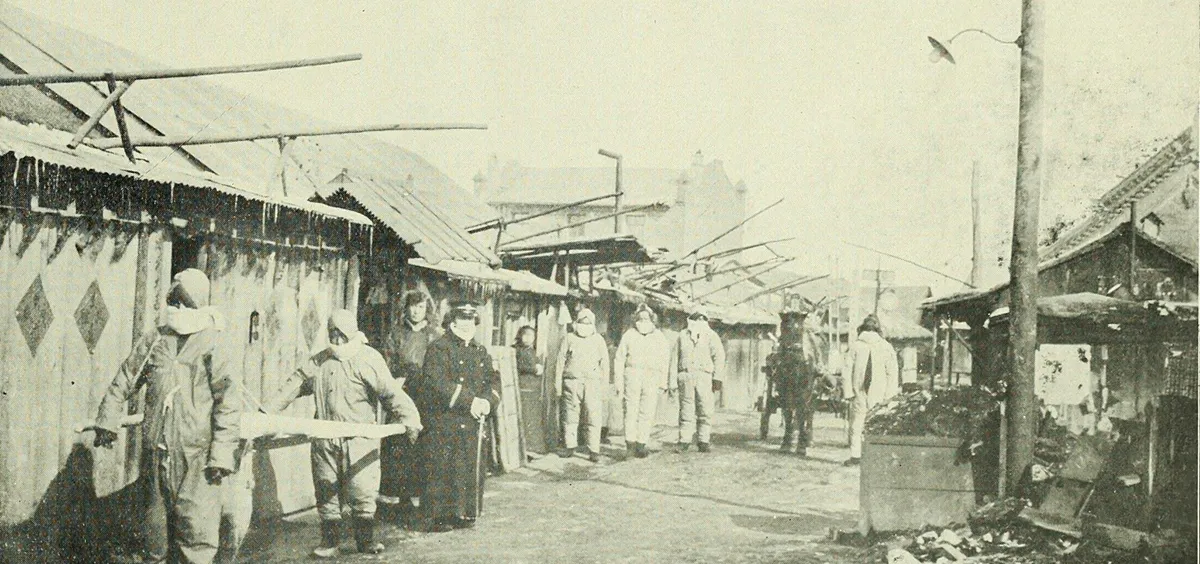

A hospital for patients suspected of having the plague in Harbin

His first task was to identify the invisible enemy: The symptoms matched those of bubonic plague, believed to be transmitted from rats to humans via fleas. Japanese experts in Harbin disagreed, however, having found no trace of the Yersinia pestis virus after dissecting hundreds of rats.

On December 27, a Harbin hostel owner died, and Wu requested to dissect the body. It was an unprecedented move: Though autopsies are well-understood today, traditional Chinese beliefs dictated that bodies should be buried intact. In fact, it was illegal to mutilate a dead body in those days, and Wu, after gaining approval from the deceased’s family, operated in the hostel secretly. The elliptical Y. pestis showed up clearly under his microscope.

A thorough search of Fujiadian traced the virus to a marmot shack connected to the fur trade, but Wu felt it was too small to explain the scale of infection. He proposed a radical alternative: that this was a new, airborne form of plague, which could pass from person to person.

Wu reported his theory to the government and asked for support. On January 2, 1911, the Qing sent Gérald Mesny, a French physician who had experience with plague, to Harbin. Unfortunately, Mesny didn’t buy Wu’s airborne theory, and even made a racist comment about his colleague. On January 5, the French expert went to the hospital to check on infected patients without any facial covering. Three days later, he began to show symptoms, and was dead by the week’s end, with Y. pestis detected in his blood.

Mesny’s death shocked the whole medical establishment, and goaded the government into taking extraordinary measures: first, by sealing off the entire northeast. From January 13, anyone who wished to travel south through Shanhai Pass needed to be quarantined for five days. Rail lines like the South Manchuria Railway and the Beijing-Tianjin Railway were taken out of service.

Bodies of plague victims were cremated to prevent further infections

Infected neighborhoods within the northeast were isolated, and residents were only permitted to move within certain districts in order to interrupt transmission. Wu also requisitioned 120 train carriages from the China Eastern Railway to use as temporary quarantine shelters.

Wu even invented a simple and cheap “anti-plague” facial mask by layering two pieces of gauze and a piece of cotton—the same principle as today’s N95 masks. The “Wu Mask (伍氏口罩)” was mass produced for ordinary people as well as the 2,943 doctors, soldiers, and others who fought against the epidemic.

On January 31, the day after Chinese New Year, Wu took another shocking measure—cremating plague victims’ bodies. Though staunchly protested by the locals, who felt this was disrespectful to the dead, Wu realized the bodies, which at the time were simply left piled on the frozen ground, had become a major source of infection. With support from the government, over 2,000 bodies in Fujiadian were thrown into pits and burned.

On March 1, 67 days after Wu arrived in Harbin, no new deaths or infections were reported in 24 hours for the first time. A few days later, Wu released Fujiadian from quarantine. An estimated 40,000 to 60,000 people died in the pneumonic plague of 1910; 7,200 deaths occurred in Fujiadian, about a third of the town’s population.

In April, Wu chaired the International Plague Conference in Shenyang, the first international academic conference held in China. A 500-page report released afterward laid the foundation for international cooperation in fighting the plague and China’s modern public health infrastructure, including measures that wrested back China’s right to customs and quarantine in its ports, which the Qing had lost to foreign powers.

Wu went on to fight against other outbreaks of plague and cholera in China, and helped found the Chinese Medical Association in 1915, as well as over 20 modern hospitals. He was nominated for a Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935, the first ethnically Chinese person to receive this honor.

“Masked Warrior” is a part of the cover story from our issue, “Contagion”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.