In China, disease control has long been associated with patriotic movements

On New Year’s Day, 1952, two Chinese soldiers on the Korean Peninsula were alarmed to hear an enemy plane circling near their bunker.

“At daybreak, we searched and found…bacterial bombs,” they reported. “There were flies and other insects…some of which we’d never seen before. There were English words [on the casing] which a university student among us recognized at once; it’s the logo of an American germ bomb!”

The accuracy and veracity of this account, and several other supposed eyewitness reports from that time, have been disputed in recent decades. At the time, though, this apparent proof of US germ warfare sent China into panic. In February, the People’s Daily began reporting US planes dropping insects and dead rats in northeastern China itself, and linked these occurrences with domestic epidemics like cholera, plague, and flu—and in the process, gave ammunition for a very different sort of war at home.

Fresh off their victory in China’s civil war in 1949, the Communist Party became embroiled in a new struggle against disease soon after the PRC’s founding. Decades of war, natural disasters, and opium addiction had ravaged the health of the Chinese, which had an average life expectancy of just 35 years, and 40,000 physicians trained in Western methods for a population of 540 million, almost all concentrated in the cities. According to a central government report from September 1950, the infectious diseases that ailed the country included plague, cholera, measles, flu, smallpox, typhoid, dysentery, typhus, leprosy, malaria, schistosomiasis, and STDs.

Sanitation workers exterminate sandflies, which spread kala-azar, in Beijing in the 1950s

Based on a model from their rural base areas, the Party set out to train local cadres in vaccination, disinfection, and pest control, and aimed to establish a clinic in every rural county and urban district in the country. However, the Americans’ perfidy gave the Party momentum for a level of grassroots involvement never attempted before. In 1952, the central government launched the “Patriotic Health Movement,” cementing an ideological link between the nation’s physical and political health that persists today.

According to Mao Zedong, the nation must “rally to emphasize sanitation, reduce disease, raise health levels, and smash the enemy’s germ warfare.” The logic was that by improving the population’s overall health, biological weapons would have less of a chance to harm them. The connection between health and patriotism also drew on China’s past humiliation by imperialist powers, which used their allegedly superior management of diseases to justify taking territory from the “sick man of Asia.”

Regardless of the actual risk of germ warfare, the movement succeeded in clearing 29 billion tons of trash, digging 1.6 million kilometers of sewage ditches, and building and renovating 85 billion lavatories by 1958. This mass enthusiasm provided a convenient foundation for the Great Leap Forward, which began that same year with the “Four Pests” movement. The whole population was mobilized to exterminate three infectious disease vectors—flies, mosquitoes, and rats—and sparrows, which were despised for eating crops, wherever they could be found.

Organized into extermination “regiments” under the regional Patriotic Health Bureaus, which often offered rewards per pest caught, children and adults across the country dug fly larvae from the ground, sprayed ditches with chemicals, and plugged up mouseholes. They stood guard in the fields, where they banged pots and pans to scare away the sparrows, or killed them with guns or slingshots. The latter actions resulted in catastrophic crop failure, as the absence of sparrows led to locust plagues. In 1960, bedbugs replaced sparrows on the Four Pests list (and were in turn replaced by cockroaches).

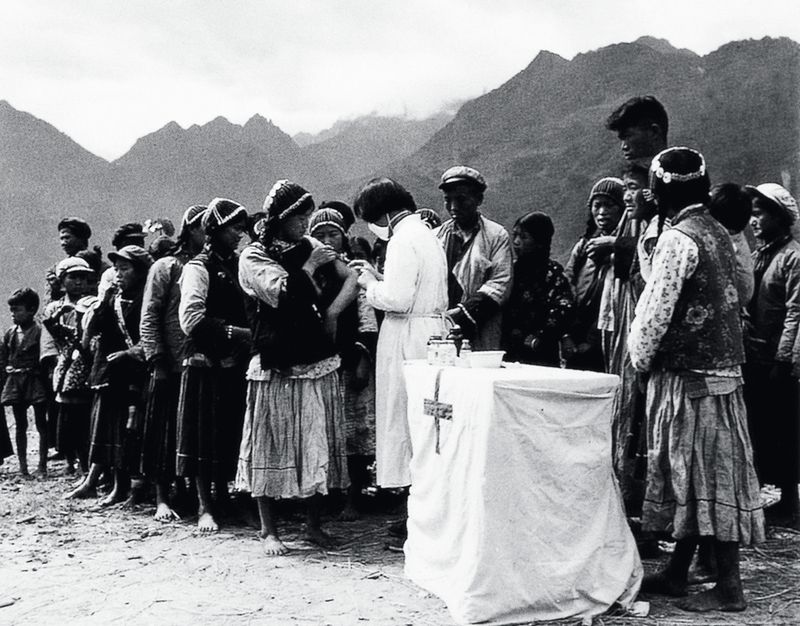

Ethnic minorities in Yunnanreceive vaccinations in the 1950s

The influence of these movements persisted into the Cultural Revolution. Just as slogans of the 50s Four Pests movement declared “Flies and mosquitoes are like rightists,” propaganda posters of the 60s compared political enemies to “pests,” and provided imagery involving sweeping or cleansing them from the nation.

On the other hand, though clinics and Patriotic Health Bureaus were shut down briefly during the Cultural Revolution, China made enormous strides in public health and disease control in the pre-reform era. There had been three nationwide smallpox vaccination movements by the 1960s, which inoculated 80 percent of China’s then-population and helped to eradicate the disease worldwide by 1980. Plague and cholera were also eradicated by the late 70s, and schistosomiasis was controlled.

The Patriotic Health Bureau has since adopted many new slogans: “Sanitary Homes” in 1978; the “Five Emphases, Four Beauties, and Three Loves” in 1987, which encouraged loyalty to the country and moral behavior in addition to sanitation. More recently, it has assisted President Xi Jinping’s “toilet revolution” for improving standards in China’s public lavatories.

However, market reforms had also reduced the political import of disease prevention. In the book Beijing Health Records, editor Liu Guozhu stated that epidemic prevention stations were only getting 5 to 8 percent of the city’s health services funding by the time SARS struck in 2003. The mismanagement of that outbreak renewed government attention on epidemic control.

Since 1989, April has been designated China’s “Patriotic Health Month.” This year, the Patriotic Health Bureau, relegated to making toilet posters in recent years, roared back into attention with a new campaign calling for the population to change unsanitary habits believed to have contributed to the Covid-19 outbreak, including “uncivilized dining behavior” such as consuming wildlife or eating from a common dish with one’s own chopsticks.

These sanitation efforts were also labeled a “movement (运动)” again for the first time since 1978 (rather than “work,” or 工作). Elderly volunteers carrying brooms and spray bottles, and perhaps memories of wielding slingshots in their youth, have gone out onto the streets to sweep, disinfect, and do their part in sanitizing the nation.

Politicizing Pandemics is a story from our issue, “Contagion.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.