The disastrous monetary policy that brought down the Nationalists

“The rickshaw passenger is not much heavier than the money needed to pay for the ride,” a British-accented announcer intones over a sensational black-and-white newsreel of a Shanghai man riding a rickshaw with bricks of cash spilling from his lap—“literally loaded with money” simply to buy groceries.

It was the summer of 1948, and from the outside looking in, Shanghai seemed to be faring well. After over a decade of war, the shops were once again full of products. Yet as historian Stella Dong notes in Shanghai: The Rise and Fall of a Decadent City 1842-1949, “This was an illusion.” Inflation was so rampant that shops in most major Chinese cities closed in the middle of day so they could readjust their prices.

“If ordinary people looked more rich, it was only because they had no choice but to spend every last dime on consumer goods before it lost value,” writes Dong. As cigarettes rose to 18 million yuan per box and a gallon of gasoline hit 3 million yuan, middle class savings were all but wiped out. The lower classes suffered even more, with a single grain of rice reaching over 100 yuan.

Ever since the Nationalist government had established control over China’s monetary system in 1935, curbing a robust private banking system, it had grappled with inflation. Wartime crises exacerbated the situation. Supposedly, the Nationalist government had to fly in Chinese currency that had been printed in Britain to fund the war against Japan.

The resumption of conflict between the Nationalist and Communist forces in 1945 intensified the financial crisis, especially as the Nationalists were cut off from much of China’s resource-rich hinterland. By the summer of 1948, the yuan was being exchanged to the US dollar at one million to one; some on-the-ground reports noted that the black-market rate was over 10 million to one.

Many decided to forgo paper money entirely as it “became as worthless as wastepaper,” as Indonesian financial magnate Mochtar Riady remembers from his studies abroad at Nanjing’s National Central University from 1948 to 1949. When classes were cancelled, Riady was left hungry and alone in his dormitory. Even the money his father sent him from overseas was no good, as local shop owners preferred bartering in goods and food.

“We Americans had become accustomed to arriving at a restaurant with a shopping bag full of cash to pay for dinner,” writes journalist Roy Rowan in his memoir of the 1949 Chinese Revolution, “or having an airline ticket invalidated right after it was purchased because the price of aviation fuel had doubled.” Many foreigners, though, had their wealth in foreign currency and simply viewed hyperinflation as an inconvenience, while truly affluent Chinese urbanites were busy converting all of their wealth into gold, silver, and jade.

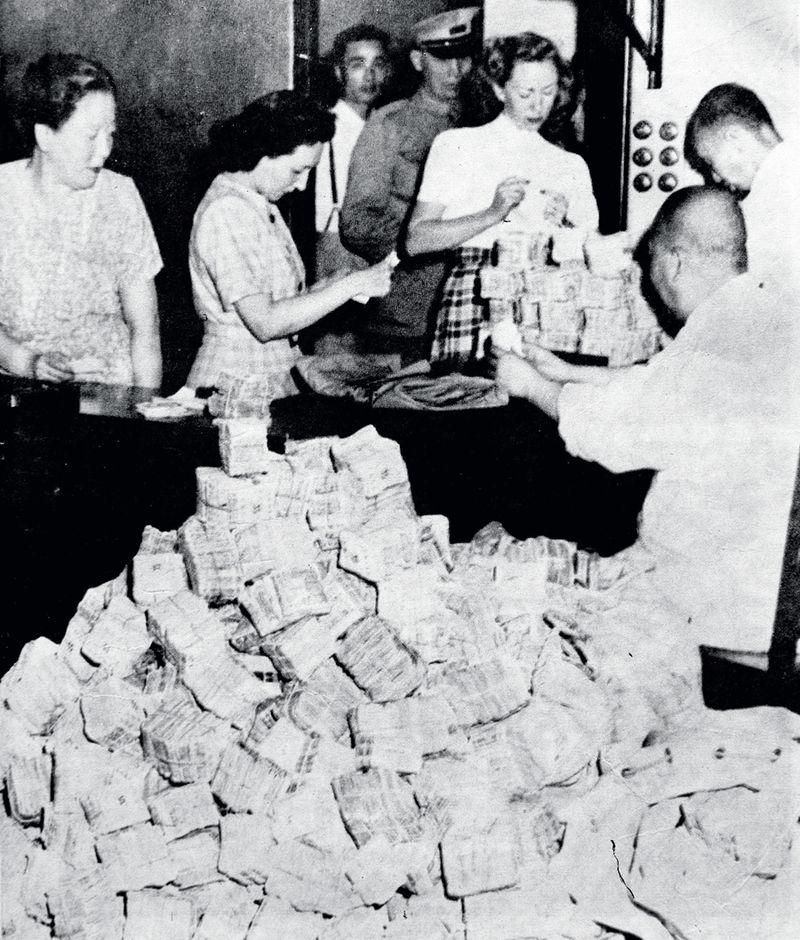

Foreigners and Chinese got used to carrying sacks of cash to go out shopping

On August 19, 1948, the Nationalist government announced it would issue a new currency called the gold yuan, which would be pegged to the US dollar. Rowan remembers the optimism he witnessed in Shanghai with “men and women waiting for hours with suitcases and basket loads of old bills” to make the exchange at the bank. The exchange rate was 12 million original yuan to one gold yuan.

However, the optimism was deceiving. Robert Doyle, Rowan’s fellow correspondent at Time-Life magazine, noted that the wealthy kept hoarding precious metals and foreign currency, and efforts to stabilize the gold yuan were fraught with uncertainty.

To ensure compliance with the exchange policy, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek froze prices and gave his son, Major General Chiang Ching-kuo, sweeping powers. “Young Chiang slashed into his job, executed one black marketeer, jailed several of Shanghai’s richest citizens,” Doyle wrote, commenting that the people then “dutifully” fell into place with the conversion.

Likely inspired by his stint studying abroad in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, Chiang Ching-kuo’s efforts against the wealthy Shanghainese “big tigers” were legendary. Described as a paramilitary organization, his Bandit Suppression National Reconstruction Corps regularly put loudspeakers in front of homes of the rich to intimidate them into converting their wealth to gold yuan. His zeal supposedly went so far that his stepmother Soong Mei-ling slapped him for imprisoning his father’s political allies.

But Chiang Ching-kuo could not stop the inevitable: Although he could coerce the Shanghai markets to establish price ceilings, he could not control the markets of Anhui, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, which often refused to accept the new currency. When the gold yuan also began to inflate, Chiang Ching-kuo resigned and apologized to the Chinese people, prompting a “gold rush” in which seven people were trampled to death as they swarmed the bank to exchange their yuan for gold.

However, the legacy of the gold yuan was about to take another unexpected turn: Late one night in 1949, Rowan encountered a hush-hush military mission to move crates of gold from the Bank of China’s vaults. At first, the Nationalist government claimed that it had to relocate the country’s gold reserves to southern China for safety. Instead, the gold was placed onto waiting ships bound for Taiwan, where it would later fund the Nationalist government’s move to the island.

Cynical observers at the time believed the gold yuan was simply a smokescreen to allow the Nationalists to amass gold before surrendering the mainland to the Communists, with Rowan tongue-in-cheek referring to it as a “golden nest egg.”

Others, including many historians, equate this often overlooked disaster of monetary policy as one of the final nails in the coffin for the Nationalists in the Chinese Civil War, eroding much needed public support as citizens saw their savings rendered obsolete.

Hyper Inflated is a story from our issue, “High Steaks.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.