How the memoirs of a Chinese American author, haunted by her parents, can help us relate to our own families

There’s something familiar about Seeing Ghosts, Kat Chow’s brave new memoir. It’s not just because it takes this Shenzhen-dwelling reviewer to Guangzhou, where her father grew up before expatriating to the US via Hong Kong. It’s not just the description of rising into the middle class in a 1980s and ’90s America that still feels like recent history.

Instead, it’s the candid, vividly detailed scenes of family life that remind me of my own mother and father. I think many readers will feel the same.

Chow’s writing stirs a memory of my own from high school. I’m chatting with my mother, who is seated at the kitchen table, describing a homework assignment to write about what influenced me. Something cautious, hopeful, and anxious widens in her eyes as she asks if I’ll write about her. Suddenly bashful, I reply that I don’t know.

Yet Chow, a former NPR reporter, delves into that challenge with a courage I can only envy. It takes bravery to reveal oneself and one’s family, especially when still so young (she’s 31 years old), and especially when tragedy is so central to that story. The book’s themes follow broadly familiar contours: life, death and unkept deathbed promises, and the grief and growth that take place before those obligations are resolved.

In Seeing Ghosts, that story unfolds in episodic scenes that flit through space and time, while also frequently switching perspectives—from first-person to the third and even to the second, when Chow speaks to the ghost of “Mommy.” (I soon stopped cringing at the childish address Chow uses throughout the book; any name repeated long enough becomes normal.) These mini-chapters draw from the rich archive kept by Chow, a former teenage diarist who interviewed family members and kept the recordings year after year, device after device.

Her writing style here isn’t postmodern per se, but builds the characters of her parents in fragmented layers around unknowable centers. Reading the memoir feels almost like flipping through a family photo album, showing the people and their surroundings but leaving a silence in their hearts. This feels even truer with Chow’s inclusion of anodyne photos of the family standing side by side, half-smiles revealing little of their fears and frustrations.

Across this constellation of scenes from the life of Chow and her parents, readers can assemble various storylines: her mother’s death and life; her father’s childhood and widowerhood; the daughters’ paths; the psychology and physicality of grief; and Chow’s thoughts on race and immigration. The most evocative writing is about death and its aftermath, as when she tells her mother’s ghost, “You stomp around in the attic of our family’s grief. The thrums and rattles from your footsteps constantly punctuate our thoughts.”

Yet Chow’s more empathic writing is about her father, who is left distracted, disheveled, and dismayed by the death of his wife, the “general” in charge of the household. Despite Chow’s feelings of neglect and resentment, her father emerges as a fascinating and fully human character. Neither villain nor hero, this complicated man is simply unprepared for the challenges that come his way.

The mentality of Chow’s father is visible in his behavior and his habit of hoarding, though Chow’s many interviews with him, from childhood through the present, never elicit a great deal of reflection from either of them. When she does get him to speak about his experience of “the American Dream,” his responses are somewhat predictable, focusing on access to freedom and opportunity while failing to probe whether he has squandered his own chance of fulfillment. Chow just wants to know whether he’s happy, without really exploring what that means.

The author presents herself similarly, with self-analysis kept to a minimum. In her we see how the immigrant experience played out in this family, with their Chinese heritage reduced largely to food, a few Cantonese phrases and death rites that feel largely disconnected from the belief systems that bore them. There is much to be written about the experience, but it’s largely left for the reader to piece together and explore on their own.

Chow’s relatively few and vaguely frightening memories of her mother clearly imprinted themselves onto her young mind. But though they’re recounted with love and honesty, they’re also not as tight or compelling as a more fictionalized account might have achieved—perhaps one that featured more scenes with the mother-ghost, with more space to give her a voice and an answer to the author’s subconscious pain and longing. I’d like to read that version for the drama, but the minimalism of Seeing Ghosts ultimately succeeds in painting a more authentic portrait of the family.

I never mustered the courage to write about my own mother, but Chow’s honest appraisal is a work her mother would probably appreciate. Her father likely does as well, maybe giving an acidic laugh as he starts to see himself through his youngest daughter’s eyes. Many readers will appreciate this opportunity to see their own families in a new light, and consider how we can miss them before they’re gone, and still find them in ourselves. – Adam Robbins

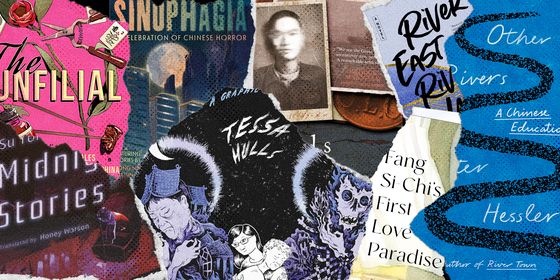

Three More Recommended Books

Ghost Forest

Canadian writer Pik-Shuen Fung’s debut novel traces a journey of self-discovery after her father passes away, leaving her with the question of how to grieve in a family that doesn’t air their emotions openly. Having grown up in Vancouver with a father who stayed in Hong Kong for work, she searches for traces of her father in her own memory, as well as that of her mother and grandmother. Sparse yet powerful prose in short vignettes cast her faraway father in shades of myth and reality, and paints the silhouette of his absence in her life. Nevertheless, the novel depicts the ways unspoken love becomes felt.

Vessel

This best-selling memoir by millennial writer and fashion executive Cai Chongda is translated into English by Dylan Levi King. Born in 1982 in a fishing village in Fujian province, Cai is forced to become the head of his household from a young age due to his father’s medical condition, and supports his family by writing, eventually becoming the youngest-ever editorial director of GQ China. In 14 essays, Cai reflects on the lessons from his childhood and his spiritual debts to his hometown. The publisher HarperVia compares Cai’s writing to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy for his unrestrained affection for where he comes from, and the investigation of his roots and becoming.

AI 2041

Kai-Fu Lee, former president of Google China, joined with acclaimed novelist Chen Qiufan to weave ten short stories that meditate on the ways artificial intelligence will disrupt the social and economic order. In cities across the world, ordinary people adapt to a world of human-machine symbiosis, autonomous weapons, and smart technology: In San Francisco, AI’s continuous replacement of human labor spurs the birth of a new “job reallocation” industry; in Mumbai, a teenage girl fights back against big data’s role in romance. Imaginative and engrossing, these prescient stories bring large existential questions to relevance on an intimately human scale. – Tina Xu (徐盈盈)

Seeing Ghosts | Book Review is a story from our issue, “Upstaged.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.