Centuries before Chanel and Hermès became status symbols, ancient Chinese could tell a person’s rank from the bag they carried

In 2020, a scene in TV drama Nothing But Thirty provoked an almighty row about the hierarchy of luxury handbags. In the show, housewife Gu Jia, the female lead, attends a social gathering with a limited-edition Chanel flap bag worth 60,000 RMB, but later finds she has been cropped out of a group photo of the event.

The reason: All the other women at the gathering carried apparently more exclusive Hermès Birkin or Kelly bags. Ashamed, Gu is forced to ask a favor from her friend, a salesclerk in a luxury store, to obtain a Kelly handbag for herself, so that she can finally gain acceptance from this circle of wealthy snobs.

On Weibo, the hashtag “Gu Jia bought a bag” received 570 million views. Many netizens expressed their surprise at the influence of a luxury bag: “One bag can divide people into many different classes!” one user commented. However, the phenomenon of using bags to indicate status is not new in China. From the first leather bags of the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) to the “fish bag” bestowed on important officials during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), ancient Chinese have been using bags to identify social hierarchy for centuries, long before Chanel got its claws into the Chinese market.

The character for bags made of cloth or leather, “包 (bāo),” has been found among inscriptions on oracle bones of the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE), while historical records mention people wearing bags since at least the Spring and Autumn period. At that time, bags made of leather were called “鞶囊 (pánnáng),” and three such bags were unearthed in the 1980s from a cluster of ancient tombs in Xinjiang—the largest satchel was made of sheepskin. Likewise, in the Classic of Poetry, China’s oldest existing collection of poetry that comprises 305 works dating from the 11th to the seventh century BCE, a verse describes people putting food in 橐 (tuó), which referred to small bags, and 囊 (náng), or big bags.

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), bags were known as “縢囊 (téngnáng).” According to the Book of Later Han, when Dong Zhuo (董卓), a military general and the de facto ruler of the Eastern Han dynasty (25 — 220), forced the emperor to move the capital from Luoyang to Chang’an (present Xi’an in Shaanxi province), many books made of silk originally stored in the imperial libraries were torn up in the chaos and turned into more practical “縢囊.”

Also in the Han dynasty, a type of square bag called a “绶囊 (shòunáng)” appeared. This bag, attached to the wearer’s belt, was mainly used to carry seals and other small items. At that time, the emperor often gave 绶囊 as gifts to government employees, so it gradually became a symbol of officialdom. This is perhaps the first time bags became directly associated with one’s social status. They also often had ornate embroidered patterns, such as animal heads—particularly tigers—and later animal paws.

This symbolism only increased in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), when there were two kinds of bag that could show one’s social status. The first was called a “笏囊 (hùnáng),” which was a bag used to carry a hu (笏), a long flat board usually made of bamboo, on which officials took notes of the emperor’s instructions at court. Most officials carried only one hu, but more senior mandarins involved in national affairs had to bring more. Thus, the bigger and fuller the bag, the more important the official.

According to the Old Book of Tang, compiled during the Five Dynasties period (907 – 960), the elderly chancellor Zhang Jiuling (张九龄) hired a servant to carry his hu bag to court for him. It soon became a fashion even among even fit and healthy officials to hire servants to bear their hu bags as an indication of just how much important government work they had to deal with.

An official’s rank could also be discerned from their “鱼袋 (yúdài),” literally “fish bag.” This was not used to pack fish, but made to carry 鱼符 (yúfú), or “fish tally”—fish-shaped tokens made of bronze, jade, or gold. The fish tally were used to prove the identity of officials, and swapped when they conducted official business or gave orders to subordinates. Poet Han Yu (韩愈), who was also an official in the Tang dynasty, described officials wearing fish bags in his poem “To My Son”: “Open the door to check who is there; just to find it’s some officials. Didn’t know whether they were of high or low station, only to see the gold fish bag hung on their jade belts.”

In the following Song dynasty, the fish tally were no longer used, but the fish bag remained, providing an even more obvious indication of an official’s seniority. Fish bags were bestowed on officials by the emperor, and the color of the bags indicated their rank. Highly-ranked officials wore purple robes and carried gold fish bags—their outfit was called “purple uniform and gold fish bag (紫金鱼袋).” Lower-ranking officials used “silver fish bags and wore red robes (绯银鱼袋).” Officials below a certain rank were not permitted to use fish bags at all.

Besides officials, scholars in ancient China could be identified by their “算袋 (suàndài),” literally “calculation bag.” Intellectuals used these to carry abacuses and other stationery like ink stones and writing brushes. In the Song dynasty, these bags were called “招文袋 (zhāowéndài, document bag)” or “刀笔囊 (dāobǐnáng, knife and pen bag).” Though all ordinary people were allowed to use these bags, they were popular mainly among literati and government officials, so wearing one was a statement of one’s education.

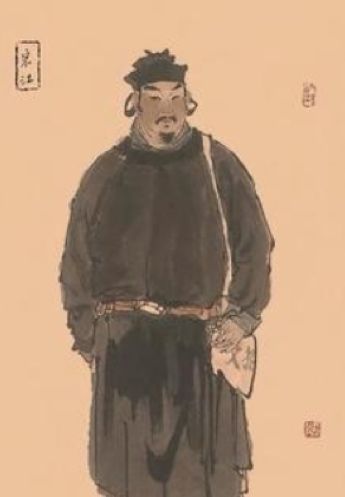

While perhaps not as fashionable as a limited-edition Chanel clutch today, using the right bag was still vital for signalling one’s social status in ancient China. And having the wrong bag could have consequences much worse than simply being cut out of a group photo: In the classic Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) novel Outlaws of the Marsh, which was set in the Song dynasty, petty official Song Jiang (宋江) murders his concubine after she snatches his zhaowen bag, which contained a letter that could prove Song had committed crime, and refuses to return it. The story at least proves that, Chanel or Hermès, fish bag or document bag, it’s actually what’s inside that counts.