Regulations and low quality in the Chinese digital scene has led the brightest of the nation’s crypto-artists to pin their hopes on international markets

The bubble burst after barely three weeks.

In late April this year, a new platform named iBox surfaced on Apple’s China App Store, trading in Chinese Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). Some users, attracted by stories of million-dollar sales and celebrity purchases of NFTs last year, and noting that the platform allowed them to re-sell, bought at lightning speed.

The products, simple digital images based on classical Chinese culture, sold at prices that inflated dramatically over a short period of time. A simple cartoon NFT of the Monkey King poised to strike a demon increased from 99 yuan to 31,588 yuan over 13 days.

But prices began to drop sharply on May 15, leaving investors (many of whom were university students) with huge losses, a lot of anger, and some fairly uninteresting pictures.

The platform continues to sell, but iBox’s plight speaks as a whole for the condition of Chinese homegrown NFTs (renamed in the Chinese sphere as “digital collectibles”). “It’s chaos,” summarizes Fan Yiwen, a crypto-artist who creates under the name of Reva. Despite her training in the Chinese Academy of Sciences as a computer graphics engineer, even writing algorithms for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, she has nothing to do with China’s digital collectibles.

In the international market, no one body or individual controls NFT trading. When NFTs change hands, the transaction is permanently recorded on a “public blockchain,” which no one platform, corporation, or individual has power over. No currency backed by any nation-state changes hands in the transaction, which is instead conducted with an autonomous crypto-currency like Bitcoin or Ether (ETH).

Although the first NFT projects emerged around 2015, when the Ethereum blockchain opened, China’s first crypto-art platform, Block Create Art (BCA), only formed in 2018. Reva first learned about NFTs in early 2020 through screenshots of tweets shared on WeChat. However it was only during the global hype surrounding NFTs last year, that platforms trying to trade NFTs began to spring up all over the Chinese internet.

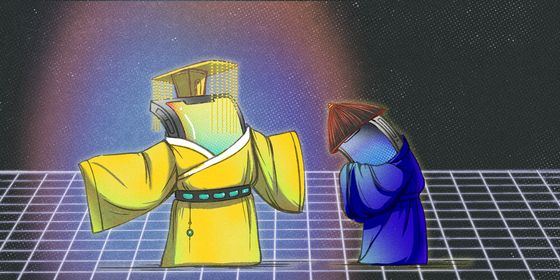

Reva, 5-hydroxytryptamine, 2021

But that’s a problem for Chinese financial regulators, who have been trying to ensure the state remains in control over the country’s increasingly powerful tech sector and to prevent the financial instability it sees in crypto. Domestic trading of crypto-currencies was outlawed as early as 2017, and the People’s Bank of China ruled all crypto-currency transactions made by Chinese abroad illegal in September 2021.

Public blockchains like Ethereum are blocked on the Chinese internet, replaced by “private blockchains” owned and controlled by platforms that sell the digital collectibles. In the summer of 2021 some Chinese companies, like Alibaba and Tencent, set up NFT platforms to try to cash in on the global hype, selling “digital collectibles” in yuan on their own platforms.

It has made digital collectibles unappealing to the best Chinese creatives. Although there has been some celebration of an NFT artist named Song Ting, a 27-year-old recent graduate of Tsinghua University who has made free digital collectibles on the Chinese side, she has also been active beyond the limited sphere of Chinese NFTs. She recently exhibited at Art Basel, and made Forbes’s 2021 list of 30 Under 30 Influential Artists.

Besides Song? Reva pauses in thought for 20 seconds when TWOC asks her who the other innovators are within Chinese digital collectibles. “I don’t know!” she eventually says, laughing.

All this, despite the government being keen to develop the technology. As early as October 2019, President Xi Jinping urged China to become a world-leader in innovative blockchain technology. State-owned companies like the National Development and Reform Commission have backed the development of the Blockchain Services Network (BSN), which has announced it will launch a Chinese public blockchain at the end of this August, named Spartan Network.

Ellwood, Three Poets No. 1, 2021

Provided they aren’t traded in a crypto-currency, Chinese companies are free to buy and sell NFTs on these blockchains. Xinhua released 10,000 NFTs on Christmas Eve 2021 on Tencent’s blockchain, the news agency saying they recorded “precious historical moments” such as images of the Communist Party’s 100th anniversary celebrations.

The trend also taps into China’s growing cultural confidence: numerous Chinese heritage sites and museums have collaborated with tech companies to create NFTs on Chinese platforms. In September last year, the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) partnered with Tencent to create NFTs featuring artwork from grottoes.

Ellwood, Twoeyes, 2021

But all the Chinese artists TWOC spoke to say that both serious young crypto-artists and established old guard in the Chinese art world are pinning their prospects beyond China’s digital collectibles.

Despite domestic regulations banning crypto and international NFT sales, artists can still create, buy, market, and sell their works internationally, all through a VPN. Some prefer to trade under pseudonyms for fear of potential government reprisals—“I think everyone tries to play it safe because Chinese policy often works retroactively,” says a member of Glimmer DAO, a so-called “Decentralized Autonomous Organization” of artists and entrepreneurs from across the world, which invests in NFTs in Asia, who for that reason requested anonymity.

Others are not concerned. “I think the regulations are not for people like me,” says Ellwood, a 31-year old crypto-artist (who gave his real name, Chen Qiji, to TWOC, unfazed), more for “the opportunists,” who buy up digital collectibles and try to sell them on for a profit.

People like Ellwood are so-called “crypto-native” artists trained and clued-up in the complex, jargon-filled world of crypto-art, preferring to create on numerous NFT platforms beyond the Great Firewall, like OpenSea. Crypto artists were using NFTs long before the global hype. For them, NFTs are a vehicle that turns digital tokens like GIFs into something that can be sold, rather than what “non-natives” mistake as a form of artwork itself.

Chinese NFT artists TWOC spoke to came from various stages of their careers, and all spoke of NFTs as something that levels the playing field. Reva originally studied computer science and worked as a computer engineer for VR art spaces for six years. This would have excluded her from many networks and professional opportunities open to conventionally trained artists. However in the crypto-art community “everyone has the opportunity to speak for themselves or be a main artist,” she says.

Ellwood, Three Poets No. 2, 2021

Ellwood had a more conventional education in art and architecture at the Maryland Institute College of Art, but started creating digital art through his interest in video games, and then found NFTs could be used to profit from them. He creates generative images of his dreams, but is also part of an international group called PillLabs that will soon be releasing “Plug Man” NFTs, customizable electric plug heads fitted onto the bodies of digital avatars. As Ellwood explains the project, “We are trying to use the NFT as the media to discuss the future human virtual identity under the framework of Web3,” referring to the idea of a decentralized internet based on blockchain technology.

China’s regulations run contrary to the ideas that originally made NFTs appealing to crypto-artists. Blockchains are designed to be impossible to shut down by any one corporation or government.

That means China’s privately owned chains are seen by the crypto community as a risk, at the mercy of both the country’s government and corporations. “If I buy a virtual sneaker [on Ethereum],” says Wu Ziyang, a VR-based artist currently teaching at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, who collaborated with Vogue to create body-positive NFTs in May this year, “then I own the sneaker, it’s mine. All these platforms could die but the sneaker is mine…but if Tencent is gone, [the sneaker’s] gone.” The Glimmer DAO representative says he has heard of cases where some artists’ work on private Chinese blockchains has been deleted for reasons unclear.

Reva, "Through the Window" collection, 2021

There are ways for Chinese artists to convert cryptocurrencies into yuan (both Reva and Ellwood have done so recently to fund their daily lifestyle), but they often use these cryptocurrencies to buy the work of other artists. “Some of the money I use as a way to make friends,” and other times as an investment, says Ellwood, .

Reva is currently reluctant to work in Chinese digital collectibles. Chinese platforms that sell NFTs “don’t care about the creative [side], they only care about money,” says Reva. According to an investigation by news media app Economic View after the iBox disaster, there are currently over 350 digital collectibles platforms on the Chinese internet, mainly created over the summer of last year. Some of them, according to Economic View, were created by big reputable companies, but others were created by less well-known entities that, despite regulations, flouted laws on copyright and re-selling.

As the law is not clear on the exact requirements regarding the sale of digital collectibles, some sites have been set up with no regulation at all. Whereas the platforms of large internet companies like JD, Tencent, and Ant Group have said they will not sell for profit and will prevent users re-selling on a secondary market, iBox charged a 5 percent commission for every transaction and allowed instant re-sale. For Reva, the work that appears on these sites is often “low effort” but “really high price.”

Wu is more blunt: He believes the Chinese side has none of the diversity he has been noticing internationally: “It’s mostly just a huge amount of shit that sells in five minutes.”

Plagiarism is also a problem. In February 2022, a professor from China’s Central Academy of Fine Art, one of the top art schools in the country, was accused of plagiarizing the well-known NFT series “Bored Ape Yacht Club,” turning them into Monkey King-themed digital collectibles. Internationally, a lack of regulation on blockchains has also proven dangerous in some cases. Pop star Jay Chou had an NFT stolen this April Fools’ Day, and 15 Bored Ape Yacht Club tokens were stolen from one collector in December 2021.

It’s partly because NFTs are still so young globally, but especially in China. Ellwood likens the Chinese field to the “Wild West” in American history: It’s a wild place, still too full of people “looking for gold.” He says he would perhaps consider working in China in the future once China’s fledgling digital collectibles scene becomes more established and the gold rush has stopped.

But for some, as long as Chinese blockchains and currencies remain in the hands of government and corporations, one major attraction of making NFTs—being part of a community which gives power to the creator, not the regulator—is simply not possible. For now, the international scene is a safer bet.

This is the second part of our series on the development of NFTs in the Chinese art world. Find Part 1 here.

Cover image by Reva, part of "The Sacred Garden" NFT collection, 2022