In a tongue-in-cheek attempt to gain control over their lives—or a means of excusing bad habits—China’s netizens are role-playing as emperors and servants

Divine Emperor, I am truly grateful for you taking time out of your busy schedule to consult this account. I suppose you are wondering why I am addressing you this way. Do not fret; simply allow me, your humble servant, to guide you through an inspection of the latest viral online trend: role-playing as you, the mighty Son of Heaven himself.

You see, some netizens in recent months have taken up the mantle of emperor (皇帝 huángdì), proudly proclaiming: “I have logged online to become an anonymous emperor (我来上网就是来微服私访的 wǒ lái shàngwǎng jiùshì lái wéifú sīfǎng de).”

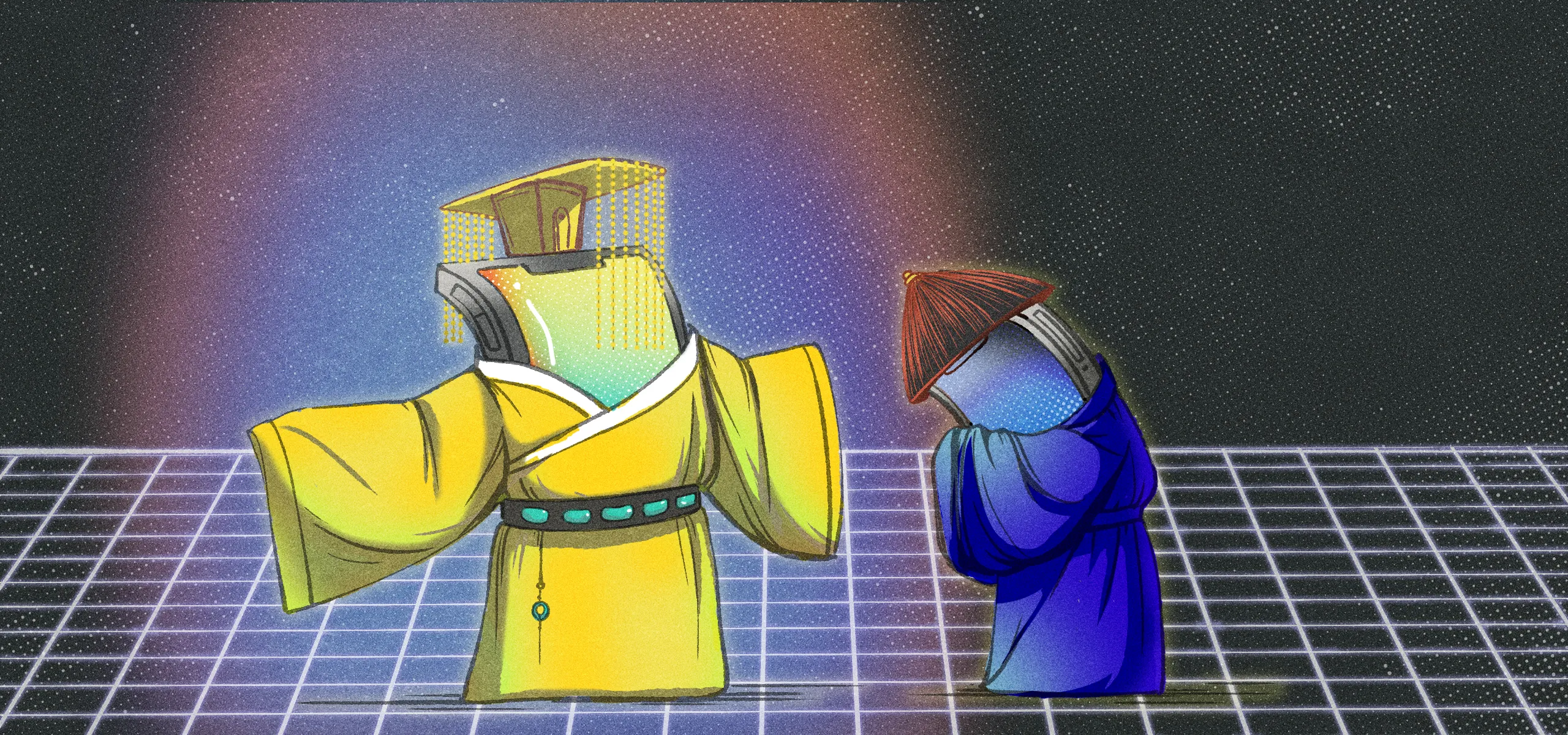

The term “cyber emperor (赛博皇帝 sàibó huángdì)” first appeared earlier this year after internet users began discussing the seemingly endless array of tasks that awaited them each morning on their phones. Upon waking, they describe being met with myriad unread messages pertaining to both personal and work affairs, rapid-fire notifications from various apps and platforms, and a succession of trending news headlines vying for their attention, each seemingly more alarmist than the last. Taken together, they complained, it can feel as though they have a country to run via the internet.

It was this sentiment that gave rise to the phrase “going online is like presiding over an emperor’s court (上网如上朝 shàngwǎng rú shàngcháo),” while “reviewing electronic memorials (批阅电子奏章 pīyuè diànzǐ zòuzhāng),” referring to the written reports once prepared for his Imperial Majesty, became shorthand for the effort needed to respond to messages or catch up with the latest news.

Discover more viral memes on the Chinese Internet:

- “Retirement Lit” is Helping China’s Youth Reimagine a Future Without Rest

- Between the Light and the Dense

- An American in Shanghai Redefines What It Means to “City”

Some netizens even shared screenshots of how they have creatively grouped apps into folders named after ancient imperial households or governmental agencies. For instance, food-delivery apps fall under “Imperial Kitchen (御膳房 yùshànfáng)”; weather apps, the “Imperial Astronomical Bureau (钦天监 Qīntiānjiàn)”; banking apps, the “Ministry of Finance (户部 Hùbù)”; and transport-related apps, the “Ministry of Works (工部 Gōngbù),” once responsible for infrastructure and civil engineering projects.

Being a cyber emperor also means unlimited access to the vast sea of information the internet has to offer, as well as its conveniences. However, heavy lies the head that wears the crown—cyber emperors must also endure the pain of having their attention endlessly fragmented, and must constantly avoid the danger of screen addiction.

Riding this tide of self-mockery, a group of vloggers began to create content acting as cyber emperors’ ministers, attracting more views with the promise of emotional support. Vlogger Yuemu Shendun, posting on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, is widely regarded as having started this trend. In a video uploaded in July, he refers to how surfing the internet and scrolling through short videos is a type of noble act undertaken by netizens:

Your Majesty, as the Son of Heaven, you personally investigate the people’s concerns. Truly, you are a divine dragon in human form, going on secret inspections in plain clothes!

陛下是以天子之身,体察民隐,实属真龙下凡,微服私访啊!

He doesn’t stop at commenting on netizens’ online habits and daily anxieties. In another video, he says:

It’s not that you have bad luck with money, nor that you’re destined to be poor. It’s just that His Majesty prefers to personally practice frugality.

你根本不是财运不佳,更不是命里没钱;陛下只是喜欢躬行节俭。

Each of these short videos has attracted hundreds of thousands of likes, prompting other vloggers to follow suit and create similar content, referring to viewers as esteemed emperors. It has also become a game among these circles to address one another with unwavering flattery, justifying and excusing a range of potentially negligent behaviors that would be unseemly had those involved not received the Mandate of Heaven:

It’s not that you don’t want to go to work, nor is it that you can’t get out of bed; Your Majesty is simply tired after attending countless affairs and laboring over state matters.

您不是不想上班,更不是起不来床,陛下您日理万机、操劳国事。

Some even go as far as to urge indulgence in such behaviors:

Your Majesty, you can do whatever you wish: you are the embodiment of heaven—who could possibly tell you to do otherwise? Please, Your Majesty, continue to scroll on your phone. Your humble servant will take their leave.

陛下您想干嘛就干嘛,您就是天理,谁能管得了您呐,陛下您接着刷手机,奴才先告退了。

As a traditional Chinese saying goes: “Honest advice is hard to hear but beneficial to follow (忠言逆耳利于行 zhōngyán nì’ěr lì yú xíng).” Given the bad counsel being promoted by these sages, they’re jokingly referred to by netizens as “treacherous digital ministers (电子奸臣 diànzǐ jiānchén).”

Much like historical rulers who willingly succumbed to the flattery of duplicitous ministers, netizens have also fallen prey to similar deception. Some coo their satisfaction by saying, “I, in my imperial majesty, am greatly pleased (朕龙颜大悦 zhèn lóngyán dàyuè).” Others remark approvingly, “My loyal minister, you have greatly endeared yourself to me (爱卿深得朕心 àiqīng shēn dé zhèn xīn).”

By harnessing humor and playfulness and indulging in sycophancy not readily available to them in real life, netizens are finding release from the pressures of daily life. And in the face of those critics who disparage such role-play as “spiritual victory tactics (精神胜利法 jīngshén shènglìfǎ)”—a defense mechanism that involves altering one’s perception of reality to avoid facing defeat or failure—any self-respecting cyber emperor would simply wave a hand and retort: “Do you really think I, as Emperor, am unable to tell loyalty from treachery? (是忠是奸,朕还分不清吗?shì zhōng shì jiān, zhèn hái fēnbuqīng ma?)”