From driving classes to police detention, a young interpreter has spent over 20 years advocating for improved sign language and better services for the Deaf in China

1

A Native Sign Language Speaker

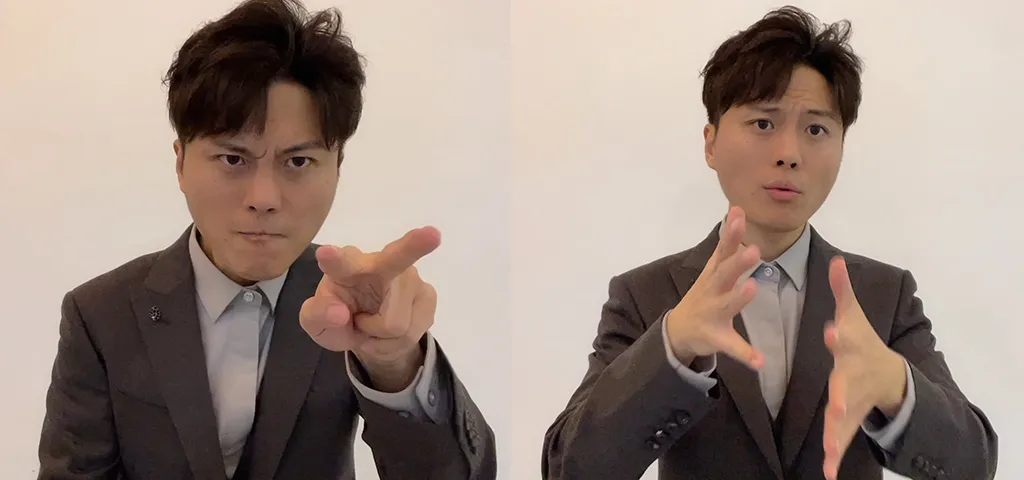

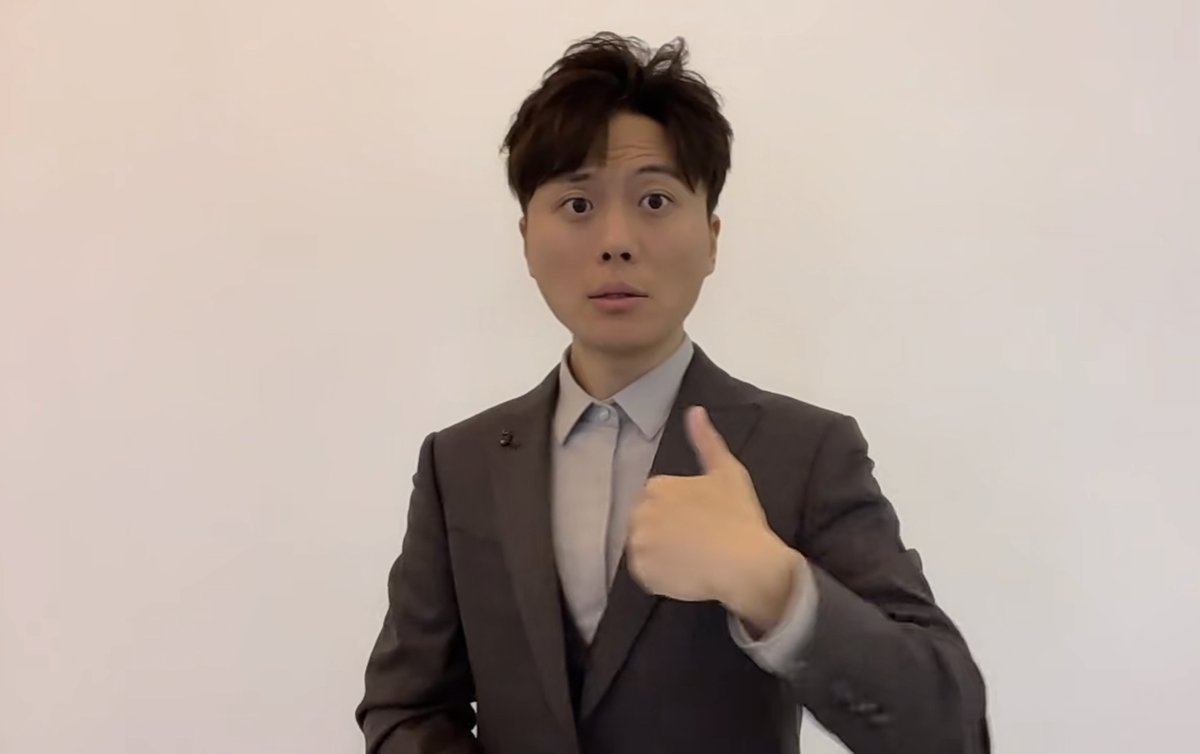

Hi everyone, Xiao Chi here. I live in Dalian, where I work as a Chinese sign language (CSL) interpreter.

My family is no ordinary family. CSL—otherwise abbreviated as ZGS—is actually my first language, though I did grow up in a bilingual environment with spoken Chinese as well. Up until my late teens, I spent every other month living with my parents, and the months in between with my maternal grandmother. My grandmother‘s was a hearing household; only my mother is deaf in their family. However, on my dad’s side of the family, my father, uncle, aunt, and great-uncle were all deaf. Their friends, who often came over for a meal or to take me out on a playdate, were deaf too.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always been aware that my parents were different from others. Here, a memory comes to mind. I must have been 7 or 8 years old, and I still slept in the same bed with my parents. One night, I suddenly woke up to this really strange impression that there was something moving in our bedroom. It was my folks, chatting under the moonlight; already at that age, I knew that sign language relies greatly on a light source. Filled with curiosity, I took careful mental note of their every movement. It dawned on me that my parents kept track of each other’s speech by touching each other’s hands and faces. It was rather romantic.

Story FM: Facial expressions and body language are just as important to sign language, serving a role similar to modal particles and adverbs in our regular speech. That’s why Xiao Chi’s parents were touching each other’s hands and faces in the dark.

Take the words “don’t know.” In CSL, you sign those by “taking your palm to your forehead, swiping to the other side, and keeping a puzzled face all throughout the sequence.” Whenever you’re describing a certain motion, your body posture reflects the degree of movement. Body posture is also crucial for you to tell different characters and their roles apart in sign language storytelling.

Xiao Chi discovered early enough that the exaggerated movements and expressions typical of sign language often attract everyone’s attention. As a child to deaf parents, mastering CSL was essential for him.

Xiao Chi: I started working as a CSL interpreter when I was about 4 or 5 years old at the family’s paint factory that employed all of my relatives—my grandfather, my aunts and uncles, and my parents, too.

Growing up, in the absence of my grandpa or a hearing employee around to answer calls from customers, I was in charge of the phone. My deaf relatives only knew there was an incoming call if they saw the phone light up.

I’d say, “Hello, this is Jianhua Paint Factory” and relay whatever order—say, a number of buckets of paint—to my mom. She’d approve and I’d say “Yes” to the customer. I’d also ask stuff like, “How many buckets for the indoor walls and how many for the outdoor walls?” And so we trudged along. Colors such as ocher were actually the most challenging to interpret, because sign language will only describe a few basic hues, but a paint factory deals with a large color catalog. My mother held up a chart for me to identify each color. If the customer wanted two barrels of pink, I’d point it out to Mom on the catalog.

2

Perfecting My Sign Language at a Driving School

Story FM: Apart from interpreting for his family, Xiao Chi also helped out his parent’s friends whenever they needed sign language assistance. However, in college, Xiao Chi actually ended up majoring in e-commerce; sign language was just part of his personal life.

In 2010, Xiao Chi had just turned 21 when he came across a recruitment notice from the local Deaf Association. His own mother had been working for the association and encouraged her son to give it a try.

XC: Back then, Dalian was setting up a driving school for the Deaf community, except they were in need of an interpreter and were unable to fill the vacancy. For all of my life experience, I did not think I was qualified for the position. After all, ours was a family-style sign language, so to speak. The gestures that our household had coined for the purpose of our communication did not align with the broader, common code of the Deaf community.

However, Mom had told me that this driving school was crucial to the Deaf community. It was one of their few chances of ever obtaining a driver’s license, and by extension any job calling for driving skills. This all relied on finding an interpreter.

I decided I would give it a try. First, I registered with the China Disabled Persons Federation (CDPF). After that, I was officially transferred to the driving school, the third of its kind in China. The other two were located in Beijing.

Because the driving lessons were in great demand in the Deaf community at the time, we had people flocking to Dalian from all across the country. To my great confusion, I found out that there are actually several dialects of CSL, and I had to deal with them all at the driving school. My previous experience was just not enough.

For Shanghai and Beijing, alone you’re already looking at significant differences between their dialectal sign languages. Beijing CSL will often borrow sounds from other words to convey meanings. For example, to say the word “trash (垃圾),” speakers of Beijing CSL will use the gestures for “bad (坏)” and “chicken (鸡),” the latter being a homophone for the second character in 垃圾. Among interpreters, we often joke that Beijing “chickens” are fighting birds, because the character is a homophone of 机 and ends up in myriad additional terms such as “favorable circumstances,” “chance,” and even “machine,” all thanks to this borrowing sounds trick.

Meanwhile, Shanghai CSL is more prone to borrowing images. For instance, you touch your chin first in order to convey the word “morning.” This is because of the understanding that people shave their beards in the morning, and as a result their chins are clean. For “afternoon,” you make a gesture under the chin to indicate the growth of stubble—in other words, the moment in the day when you’re likely to grow your beard back.

Shifting gears, stepping on and releasing the clutch pedal, turning at street lights…these and other concepts had yet to be standardized in sign language. Our only choice was making them up ourselves, so we got right to work by teaching the students to correlate direct action with sign language commands. For example, I’d engage the gear while using a specific sign language term, so that they’d connect the two.

The coach, our first cohort of students, and myself gradually figured out a process of sorts where we created a working sign language that belonged to our tiny driving school community. For the system to work, the coach had to remain in the passenger seat at all times, and I was to stand outside the vehicle, right in front of the windshield, interpreting for the students.

I tanned something fierce in the summer, and zipped up my down jacket in the winter. We all stayed together virtually 24 hours a day. As the only CSL interpreter in the driving school, I served almost 1,800 students during my years there, sharing their mealtimes and practically living with them at the venue.

Two years on, I started being invited as an interpreter to local conferences and other large-scale events for the Deaf community, and I was oozing confidence about my skills. I pretty much felt invincible. I really was filled with this boyish, naïve pride.

One evening, I got home to my dad having his dinner and I bragged to him. “I really am the boss now. Just ask anyone in the community.” So what did my dad do? He went off at me in the most specific sign language in his repertoire. Then, he threw the gauntlet at me. “Please interpret what I just said.” I hadn’t understood a thing. In fact, my mind was dizzy, and I sulked back to my room, defeated.

The incident made me shelve my cockiness. Instead, I dedicated myself to dissecting the speech of deaf people, down to their every movement. Where I’d once aimed at quantity, I now pursued quality and depth. Mealtimes and break times at the driving school were study times for me, and I didn’t hesitate to interrupt conversations to ask about a single word that escaped me. I’d grab the student’s hand and ask them to explain that term to me. You’d think I was the epitome of rudeness, but in fact deaf folks really appreciated my behavior.

With every word I learned came the need to remember it and make sure it was widely used in the Deaf community. This means I‘d deliberately find a way to introduce this sign in conversation with a deaf person, and check if they understood it.

This all-consuming process took another two or three years. But the experience earned me my father’s acknowledgment. “Now those are some amazing skills you got there.”

Story FM: Patience and sign language learning go hand in hand. Xiao Chi had to verify the universality of the sign language he learned at the driving school, and he also had to pay attention to the generational differences in speech from young, middle-aged, and elderly deaf people.

Beginner sign language users tend to be more verbose. Over time, as they communicate more and more, they boil down the language to a more general, concise vocabulary.

Xiao Chi spent five years at the driving school. On paper, he was merely responsible for interpreting the lessons. In reality, he helped the students with all their communication needs, from food to clothing, housing, transportation, and liaising with the driving school. His students were his teachers, no matter their age.

3

A Language That Serves Everyday Needs

XC: In 2016, Dalian held a sign language competition. “Give it a go, Xiao Chi!” Many in the Deaf community encouraged me to participate.

I was confident that I’d reached a certain level as an interpreter. However, at the sign-up for the competition I found that there were two categories—professionals and amateurs. A staff member rang me up and tried to persuade me to sign up for the latter. “Xiao Chi, hear me out, don’t apply for the professional group. You’d compete against real professionals, either teachers or folks from the China Disabled Persons Federation. You wouldn’t stand a chance; your sign language is more of a grassroots thing.”

Color me confused—I asked my deaf friends for advice, but they all were of the same mind: “Go sign up with the pros!”

On the day of the competition, I was 12th in line out of 20 competitors. We were to face a two-way interpreting test—Chinese into CSL and vice versa. There was also a self-introduction portion, as well as another section for free expression.

But something caught my attention. Where my rivals had more than a few deaf members of the audience squirming in their seats or dozing off, they paid close attention to me, beaming with anticipation and unmistakable support. Once I was done, there was a thunderous round of applause from the audience. Some even gave me a standing ovation. I won first place with 98 points in the first part of the competition and 89 for the second portion.

As it turned out, there were more than a few big names also present in the audience, including several senior sign language interpreters. One of them was Professor Gu Dingqian, the author of the Chinese Universal Sign Language Dictionary. The most renowned among this impressive group was Fang Hong, vice-principal of the Suzhou School for the Blind and Deaf, who greeted me excitedly at the end of the competition. “Young man, you’re a treasure trove! There’s a brilliant future ahead of you if you keep up with your training.”

Now I was even more confused. I was not familiar with any of these judges and teachers. Just why were they singing my praises like that?

Story FM: Many people’s first encounter with sign language is likely via the TV news broadcasts that sometimes feature a tiny window offering sign language interpretation.

The CSL you see in those inconspicuous windows is known as “grammar sign language,” and it’s the very same variety that Xiao Chi’s rivals displayed at the competition. It is largely based on mere visual derivatives of Chinese, and it usually relies on a word-for-word interpretation of the spoken language of news broadcasts. Studies have shown that 80 percent of deaf people report understanding only half of this variant, or less.

In his youth, Xiao Chi used to help his parents make sense of the small windows on the screen, too. Whenever they were able to understand a couple of sentences, they were elated and cheered one another.

When Xiao Chi swept the podium at that competition in 2017, he did so with a natural CSL that had been tailored in every possible way to suit the habits and needs of the Deaf community. That’s why they could fully understand it.

XC: I only truly understood what thwarted the development of CSL after many more years of working across the country and connecting with researchers. Traditionally, CSL had followed the word order of spoken Chinese. Many researchers felt that this was the only real sign language, and so they looked down on the variants that deaf folks actually use in their daily lives.

These days, though, there is a shift toward a more natural, pragmatic CSL, both in the academic and professional spheres. Those of us at the margins may not have been aware of the trend at the time, but a transition was in process.

Though I’m only in my 30s now, I finally understand why those deaf folks so much older than myself celebrated my triumph at the competition. In fact, I would now cheer along with them if I saw someone in their 20s using fluent sign language. After all, we need to pass on our knowledge to the next generation. Winning the competition made me impervious to any suggestion that my sign language was too rustic or backward. I was finally aware of the value of my work.

4

Embracing My Role

After the competition, I went back to my ordinary life. I couldn’t say that any of that recognition had helped improve my working conditions. Yes, my job was fulfilling, but my monthly wages were barely over 2,000 yuan. For a while, I really wanted to switch careers. Then, something happened that made me change my mind and continue being a sign language interpreter.

One year, some 40 or 50 deaf people pooled some money to hire a driver, rent a tour bus, and set off from Liaoning province on a road trip all over the country. Their bus overturned on the highway passing through Beihai city, Guangxi. Two of them died on the spot, with many others injured. I got the sudden call at four o’clock in the afternoon: “Pack your things and rush to the airport, right away.” I was completely unprepared, and my wife was just as confused. “What’s the matter? Where are you going?” “Looks like I’m headed south for an emergency,” I replied. “Some traffic accident over there involving deaf people.”

By the time I finally landed in Beihai Airport, it was already two or three o’clock in the morning. Because sign language in Guangxi was not nearly as developed, the rescue and medical teams had greatly struggled to find out any details about the victims. Almost a whole day had passed since the accident, and I was tasked with filling in the significant communication gaps for this large group of deaf travelers across three different hospitals.

Some of the victims had sustained fractures such that they could only use one of their hands to communicate. Some had cranial fractures that required extensive dressing, with only one eye uncovered to see. I had to adjust my interpreting to the limitations imposed by these injuries, and often I had to repeatedly confirm their personal details. All in all, it took a whole morning plus a couple of hours in the afternoon.

I was met at one of the hospitals by the son of one of the victims who’d had to undergo surgery immediately after the accident. “My mother was complaining of pain after the surgery, but she couldn’t get her point across, so they weren’t thorough and she still has over a dozen glass shards in her legs.”

Only the woman’s son had been able to really understand her and request an additional scan. That was when I realized I couldn’t possibly quit my job. What’s more, we needed more CSL interpreters if we were to truly assist deaf people in vulnerable situations like this one.

The victims’ children trickled into the hospital over the next couple days. There were two patients hailing from Dalian and Shenyang. The former had a daughter able to take on interpreting duties immediately upon arrival, but the patient from Shenyang was not so lucky. Even her daughter couldn’t help with the interpreting.

This is how they made do. The patient from Shenyang expressed her needs to the patient from Dalian, whom interpreted everything into their regional sign language. Then, the daughter of the Dalian patient conveyed everything to the healthcare workers.

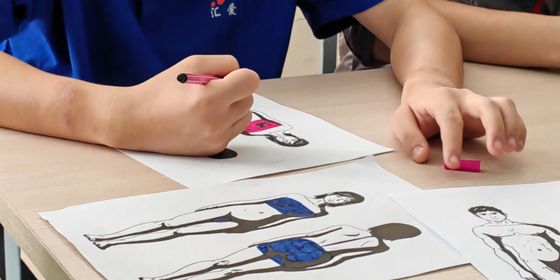

This inspired me greatly. I could gather the children of deaf adults and train them as a group able to respond in emergencies like this. So, that’s exactly what I did. The group is still active today, with nearly one hundred people from all over the country.

5

The Thief Who Wouldn’t Confess

Story FM: Xiao Chi has since served the Deaf community all across China. His hope is that he’ll be able to assist them in every possible circumstance, from birth to death—weddings, funeral services, medical treatment, travels and even more sensitive matters, such as disputes between deaf parents and their hearing children.

Deaf people are also sometimes involved in criminal proceedings where they must communicate with the police officers and the courts. So, here’s yet another crucial need for assistance.

XC: The police once called requesting my interpreting services in a case of theft involving a deaf suspect. So, I drove there the next day.

As it turned out, despite extensive evidence against the suspect from video recordings and witnesses, the guy apparently wouldn’t admit to the crime. Why so stubborn, I wondered to myself? Such a minor offense would barely keep him behind bars for a couple months or so.

At the detention center, I met a man who seemed rather ill at ease. “Hello, where are you from? I have been assigned as your sign language interpreter for this case.” The man sprung up from his seat excitedly and said to me, “Oh, I can understand you! Would you please help me explain the situation to the police?”

I asked him whether he committed the crime. “Yes.” “Then why wouldn’t you confess?” “Huh? I did...”

The policeman was also confused. “But, he refused to confess with two of our own interpreters.” To this, the detainee replied, “I couldn’t understand them...”

The suspect had only a first-grade education, so he couldn’t even write his own name clearly. In the end, though, the man acknowledged everything, signed where appropriate, and the matter was over. But, this was yet another instance of a troublesome situation rooted in the problems with sign language communication.

From my own understanding, the current market of sign language interpreters can be divided into three groups. I belong in the first group, which is usually known as CODA (Children of Deaf Adults). The second group consists of interpreters who have received professional training. The third, broader category includes self-taught aficionados who were motivated by interest or personal reasons.

Each group has its own separate interpreting strategies and methods. As CODA, we grew up using sign language as a crucial tool to ask for things from our parents. Getting whatever we were asking for relied on our mutual understanding. Meanwhile, those trained at academic institutions or self-taught tended to start from vocabulary or sentences.

Take the following command: “Mom, I want to eat an apple.” A child of deaf adults may not resort to the word “apple” first, but rather sign for description words such as “sweet,” “crunchy,” “big,” or “round.” Professional interpreters can only draw their knowledge from books, but no matter how vast this knowledge is, it may not be useful in a real-life context.

Story FM: Xiao Chi increasingly realized that the most pressing issue for the Deaf community was access to information. This came into play specially with legal problems and incidents of fraud. Deaf and hard of hearing people were often easily swindled. To a certain extent, this is due to a lack of basic life experience, but it is also a consequence of their lack of access to information.

Most people in the Deaf community also lack an understanding of the law. In more than a few cases, investigations reveal that they were not aware that they’d committed an offense.

As a child to deaf parents, Xiao Chi is better equipped to understand the plight of the Deaf community. What’s more, he supplemented this knowledge by poring over psychology books that helped him in tackling the challenges faced during his days at work.

XC: Once, there was a case of fraud within the Deaf community. The scammer was actually a hearing child of deaf adults who took advantage of his sign language skills to deceive many deaf people.

This fraudster printed lots of counterfeit deeds to real estate and claimed to know some construction bigwig who was in dire need of selling off his properties. These homes were originally on the market for over 1 million yuan, but he secured a special price—just 200,000 yuan. He compounded his wrongdoings with a huge batch of fake driver’s licenses sold for a bargain—just 30,000 yuan. No need for an exam, he said; in fact, no need to even take driving lessons.

Some 20 people fell into his trap. They placed great trust in children of deaf adults; his ruse relied on the sense of closeness and shared identity that his status granted him within the Deaf community. In fact, his parents were also involved in the fraud and fully aware of it.

In the end, they were all convicted, and I acted as a sign interpreter for the parents. They both claimed that “This is all our son’s doing, and we’ve got nothing to do with it.” A young intern was with me on this occasion. When we left the detention center, he seemed to be shocked. “How could any parent be like this?” he wondered aloud. “How could they pass blame their wrongdoing on their son?”

But my experience with the Deaf community made me think that this was not necessarily a case of unloving parents throwing their child under the bus. Those two had likely assumed that since their son was the mastermind, they were not at fault. This is how it went for a lot of deaf offenders. The police arrive to detain them and they are appalled and fail to understand that their actions did indeed amount to a criminal offense.

Deaf people end up more often than not deprived of education, too. Then, written texts become just as insurmountable a challenge for them. The radio is a no-go, as is hearing people’s speech, and since TV subtitles are also insufficient, deaf people are left to their devices in this society that fails to provide them with access to crucial information.

Today, online money transfers are possible with just a swipe of the finger or facial recognition. There are communities of vulnerable deaf people lacking any kind of self-protection against fraud, with low education and legal awareness. Cases like the one I just shared have been on the rise, particularly in the last two years. At the end of the day, a sign language interpreter is meant to act as a bridge.

Without our services, deaf and hard of hearing people find themselves on this isolated island of sorts.

Helen Keller, the American author and disability rights advocate who was famously deaf and blind, was once asked by a reporter, “If you had to choose between being deaf or blind in your next life, what would be your choice?” She reportedly answered she’d choose to remain blind: Blindness brings a barrier between people and things. Deafness places that same barrier between people.

6

An Island of Silence

Story FM: During the three years of the pandemic, Xiao Chi devoted himself to running his own social media account where he shares his interpreting of relevant news and policies for the Deaf and hard of hearing community.

Whether it’s about a virus or some new technology, every piece of news that doesn’t reach the Deaf community increases their vulnerability and deprives them of the ability to respond quickly. Physical obstacles then often evolve into mental barriers.

What about hearing people? Do they spare any thought for the Deaf community in their daily lives? Do they have any need for them? The general consensus nowadays in China seems to be that deaf people are a vulnerable group in need of assistance and support.

XC: Hearing people usually rely on their professional networks, job fairs, and the internet to find employment. But I’ve found that most of the deaf people around me find jobs through their acquaintances, recruiting each other for jobs. Again, you have to proceed with caution here; not all intermediaries have your best interest in mind, and some deaf people have no qualms about taking advantage of their peers.

Here, we find that deaf people are again far more likely to blindly trust someone from their community. So, even though deaf folks are part of society, they’re subject to this intangible isolation from the outside world.

Story FM: Near the end of the interview, Xiao Chi’s wife came into the room with two fruit platters. Afraid to interrupt the recording, she signed her message to Xiao Chi.

Three hearing people, one quiet room: At that moment, our producer suddenly realized that she was the only person who couldn’t hear what was being said.

Produced by Yin Xuan (印璇)

Images from Xiao Chi

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).