In the face of increasingly extreme weather conditions, unlikely bonds are being forged in the southern province between concerned citizens and the growers of their produce

In a bustling square in Guangzhou’s southern Haizhu district, a group of young activists are performing a play about a local farmer’s struggle after a failed lychee harvest. Nearby, an art exhibit documents how the sale of lychees in local markets, once a common sight, is becoming increasingly rare. Both events unfolded at the Canton Harvest Festival, organized by local NGOs specializing in urban-rural development on December 1, 2024, focusing on agricultural products, sustainable development, and eco-farming, which emphasizes using natural processes to reduce environmental impacts. As reflected in their choice of topics, the festival took on a somber tone, with lychees—the region’s signature fruit—being notably absent. Their dwindling yields are quickly becoming a symbol of Guangdong’s agrarian loss.

The southern province, which produces more than half of the country’s lychee fruit (an average of 1.5 million tons annually since 2021), experienced a drastic decline in harvests in 2024, marking a historic year for lychee shortages. According to the official reports, last year’s supplies fell by over 50 percent, a staggering hit to the industry.

Extreme weather events that hit the region and lasted throughout 2024’s lychee-growing seasons were a major cause of this unprecedented plummet in output. This was the knock-on effect of 2023 being China’s hottest year on record, with the warmer-than-usual winter robbing lychee trees of the cooler temperatures needed to produce buds and greatly reducing the number of flowers in spring. Then came consecutive months of heavy rain, with April recording its heaviest rainfall ever—nearly 50 centimeters, a remarkable 181 percent increase compared to the historical average for the same period. The overwatering caused widespread flower and fruit drops, further devastating lychee crops.

Read More About the Impact of Climate Change in China:

- A Year of Climate Challenge: China’s Top Environmental Stories in 2024

- Troubled Waters: A Lakeside Village Struggles to Adapt to China’s Landmark Fishing Ban

- Into the Eye: China’s Intrepid Storm Chasers

Facing the likelihood of more extreme climate events that have already decimated lychee harvests in the region, local eco-farmers and artists are, respectively, seeking innovative ways to adapt to increasingly unpredictable weather and bring awareness to the fruit’s plight. The uncertainties brought by climate change have brought these workers and activists together to navigate the challenges ahead.

The “worst ever” year for lychee farmers

For many in Guangdong, 2024 was the “worst year ever” for lychee farming. In Conghua, a suburban district of Guangzhou known for its lychee industry, a 40-something farmer surnamed Luo tells TWOC that he only managed to collect 10 percent of his usual yield, roughly 1,000 jin (500 kilograms), from his 30-mu (2-hectare) lychee orchard last year, a fraction of what his family has reaped for decades.

A nearby eco-farmer, Guo Rui, who has been cultivating vegetables and fruits—including lychees and their smaller, less sweet relative longans—since 2013, shares a similar experience. His eco-farm usually yields around 800 jin (400 kilograms) of lychees, but last year saw a “total loss.” Guo bemoans that he “didn’t get to eat one single lychee,” adding his longan yield was also the smallest since he began farming.

The continuous rains are largely to blame for the crop failure last spring, which left a deep impression on farmers like Guo. “You could count the number of sunny days on one hand,” he says. According to weather reports, Guangzhou saw just ten dry days in April, and even then, the skies remained overcast. Guo adds that he has to beat the clock and finish the farm work during the brief lulls in the rain.

The financial impact of the failed harvest was substantial. Guo estimates his losses to be 300,000 yuan (including crop failure plus the cost of machine maintenance), 1.5 times that of 2023. For farmers in the region, the climate crisis is no longer an abstract concern, but instead a harsh reality they must confront. “Extreme climate will become a major trend, and farming will only become harder,” Guo laments.

Indeed, China’s agriculture industry stands to be hit particularly hard by such conditions. Extreme flooding in the central Henan province in 2021 led to corn yield losses of over 12 percent. Droughts in 2022 in the eastern Jiangxi province’s Poyang Lake area, the largest freshwater lake in China, triggered a crisis, threatening the region’s late-season rice harvest. The severe water shortages posed significant challenges for farmers and local authorities, who struggled to mitigate the impact. Eco-smallholders, producing smaller yields than conventional farms, are even more susceptible to such losses. Yet some, like Guo, who believe in leveraging ecosystems’ natural stabilizing systems to grow crops in harmony with nature, are leading the way in implementing adaptive measures.

New experiments in farming

When TWOC visited Guo’s eco-farm in Yinlin village on December 10, his lychee trees were just beginning to bud for the upcoming growing season, a critical time in the harvest cycle. The good news is that this winter has been more favorable for lychee growing, with trees being granted the necessary chill hours required to bloom come spring. But Guo remains cautious about the season ahead. For him and farmers like him, the most significant impact brought by climate change is its unpredictability. “The old ways of farming by following solar terms are no longer reliable,” he says.

In an attempt to mitigate the impacts of this variability, Guo has focused on improving his soil’s health, which he believes can increase his crops’ resilience to extreme conditions. As opposed to conventional farming, which often involves chemical fertilizers and other materials that can lead to soil compaction and poor aeration, Guo has, over the years, developed a method of composting with herbal residues, preserving the soil’s delicate ecosystem and enhancing its fertility. “If the soil structure is good, it can quickly drain water even in situations like the excessive rainfalls seen in Guangdong. It also has better drought resistance toward extreme heat,” Guo explains.

Guo is also diversifying his crop production. He tells TWOC that he intends this year to grow more moisture-loving crops such as bananas, papayas, and sugarcane to reduce the risks of climate-related losses. “Different crops have varying climate adaptability. If one crop fails due to this year’s weather, others may still yield a harvest. For small-scale farmers like us, this helps reduce the overall loss,” says Guo.

Meanwhile, Wang Pengcheng, another eco-farmer in Conghua, is experimenting with different orchard management techniques. Wang’s orchard spans about 40 mu (2.6 hectares) and is home to over 200 lychee trees aged between 30 and 40 years old. In the past, the orchard’s average annual lychee harvest ranged from 1,000 to 3,000 jin (500 to 1,500 kilograms). But last year, it yielded only “20 lychees.” Wang tells TWOC that it is precisely because of last year’s extreme weather events that he decides to modify his approach.

Wang’s first step is to prune his lychee trees differently. Traditionally, lychee farmers keep their trees short to facilitate harvesting, cutting off the higher offshoots of the main trunk and leaving the lower branches intact. But Wang now lets the trunk grow taller while trimming away excess side branches. Wang believes that this approach better aligns with the natural growth pattern of lychee trees. “Once the main trunk reaches a certain height, and space is available around it, the tree will redistribute its nutrients and grow horizontal branches, potentially increasing fruit production,” he explains.

Wang’s second experiment involves tying small sandbags to the branches to encourage them to droop, a technique used by citrus farmers to increase fruit bearing. He hopes that cultivating stronger branches will make his lychee trees less susceptible to extreme weather conditions.

Guo and Wang are part of a growing cohort of farmers in China adopting climate-resilient agricultural practices as unusual weather patterns become more frequent. According to environmental news site Dialogue Earth, some eco-farmers in Beijing, facing unprecedented heat, have also started planting larger trees to provide shade for themselves and their crops, as well as digging ponds to collect excess rain runoff for later irrigation. Meanwhile, in rural Yunnan province, communities are transitioning from flooding rice paddies to furrow irrigation, a method that reduces water usage as well as methane emissions.

Wang, who moved from a career in electrical engineering to farming a decade ago, now focuses on promoting natural farming methods as a solution to food safety and climate issues. He believes that the answer to bolstering food cultivation and tackling climate issues lies in the same approach: “They all require a return to nature-based solutions.”

Emerging artistic action

While farmers experiment with new agricultural methods, local artists are using their platform to raise awareness about such challenges, in particular, among consumers.

One such person is Yang Lei, a 30-year-old community worker who collaborated with the NGO China Youth Climate Action Network (CYCAN) last year to write a play depicting a local farming family’s struggle with lychee crop failures. The play was performed on December 1, during the Canton Harvest Festival, to approximately two dozen people. During the performance, Yang invited the audience to participate in a discussion about potential solutions for farmers affected by the lychee crop loss.

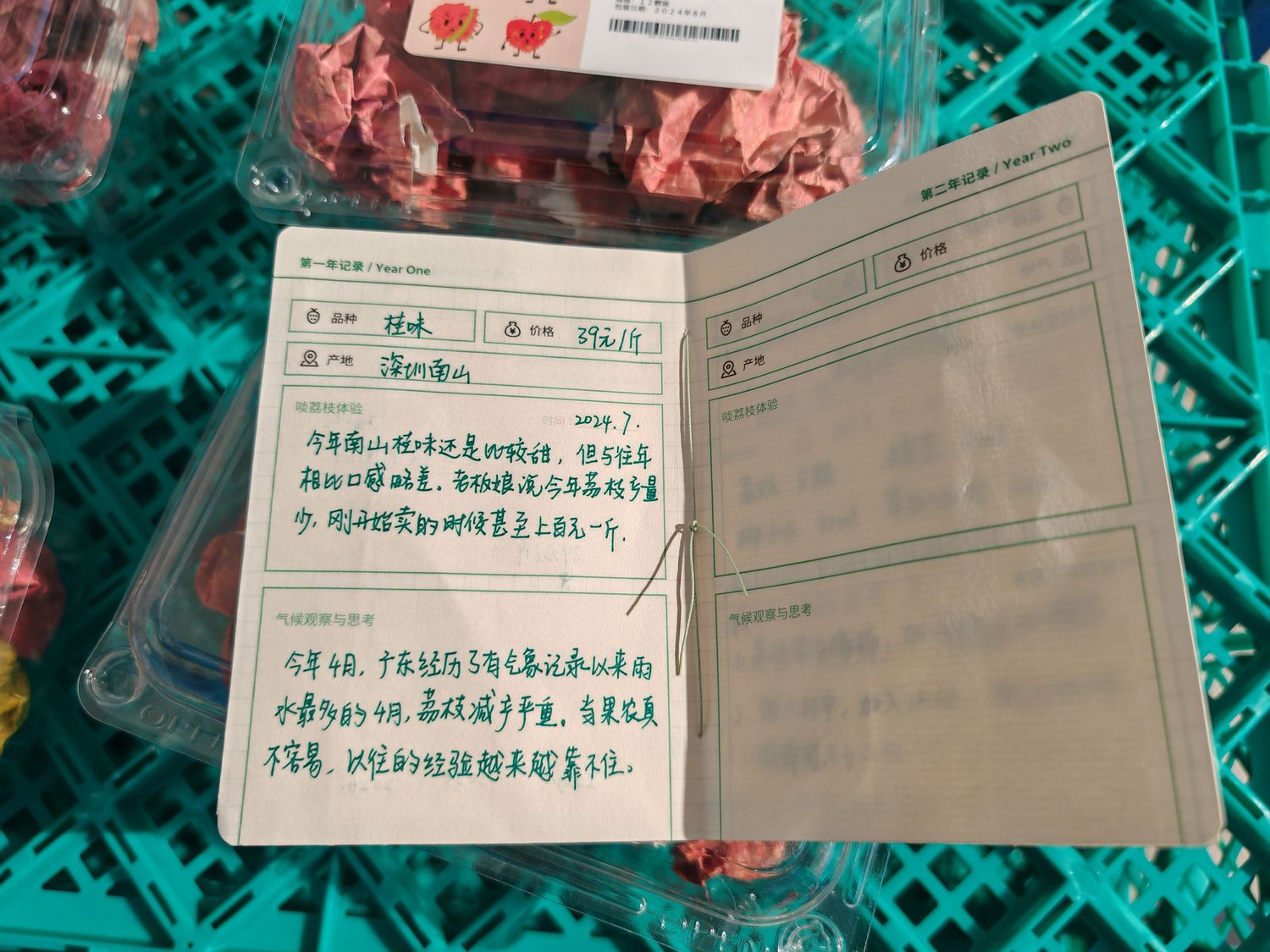

At the same festival, 28-year-old freelance artist Zhang Nianqi held an exhibition centered around the same issue. Growing up in nearby Shenzhen, Zhang used to pick fruit at local lychee orchards as a child. “When I saw the news about the lychee crop failure in June last year, it came to me that this was something I wanted to help with,” she recalls. In collaboration with a local creative organization, imPACKED, she recruited 15 participants from across the country to survey lychee availability in their local markets, documenting prices and engaging with sellers. Participants were also invited to share their observations and thoughts on climate change during the process, which too, were compiled and exhibited. Finally, Zhang headed a round table discussion with local lychee farmers at the opening to learn about their specific challenges.

For Yang and Zhang, raising awareness among consumers, especially those in urban areas, about the plight of these farmers is an important step. Yang, who has been working on community development in villages around Shenzhen for three years, recognizes that beneath the broad issue of climate change lies deeper challenges, such as the country’s uneven urban-rural development. For example, many urban consumers, disconnected from rural areas, may know little of events like the decline of lychee harvests. “The primary goal of our play was to present the story of last year’s lychee harvest failure in Guangdong as fully as possible, helping [urban] consumers understand what happened, and more importantly, how it affected the farmers,” he explains.

Some of the audience’s reactions during the performance affirmed Yang’s observations. He says that few attendants knew of the poor lychee yields, with some voicing superficial understanding about the farmers’ situations, such as assuming they could simply move to cities for work in the event of failed harvests. Yang thinks this simplified perspective neglects the complex realities farmers face or their proactive efforts to address the problem. “We hope that through the performance, we could help bridge this gap by fostering more empathy between consumers and farmers,” he adds.

Zhang views these artistic actions as planting a “seed” among consumers. “Over time, people may realize how their food consumption is linked to crop farming and even climate change, and understand why these issues are important to their lives,” she says.

Wang, a participant in Zhang’s round table discussion, offers insight from a farmer’s perspective, saying that while the impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly severe, at least for farmers like him, many people still fail to fully grasp the urgency of the issue. Although he acknowledges artistic initiatives like Zhang’s may have limited direct benefits or immediate impact on farmers, he still values their action to raise public awareness of the challenges and difficulties faced by those in agriculture.

For Wang, the root of the climate change crisis lies in society’s current mindset toward development, where the relentless pursuit of progress often drives industrial growth and increased food production, accompanied by excessive and improper chemical use that harms the environment. “Unless such a mindset is altered, only then can people start to think about how to tackle the problems of climate change,” Wang believes.

He adds that even those unable to contribute to the field of agriculture can take steps in their respective industries or professions to mitigate their effects on the environment. Farmers, for one, can transition toward more ecological or sustainable farming practices, while those working in other industries can aim to reduce carbon emissions in their own sectors. “Ultimately, climate change affects everyone, and we all have a responsibility to take action,” says Wang.

As Lychee Harvests Dwindle, Guangdong’s Farmers and Artists Ponder How to Take on Climate Change is a story from our issue, “Youthful Nostalgia.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.