Mastering the word underpinning everything from imagination and creation to conceptualization and transformation

Constructing a wooden palace without a single nail was no miracle in ancient China—people had been doing it for nearly 7,000 years. In the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, the Neolithic Hemudu people adapted to the region’s wet climate by constructing stilt houses from wood and bamboo. They were the earliest known users of mortise-and-tenon (榫卯 sǔnmǎo) joints, a joinery technique that later became a central feature of traditional Chinese architecture. These precisely carved wooden components fit together securely without the need for nails, allowing homes to be elevated, kept dry, and protected from pests.

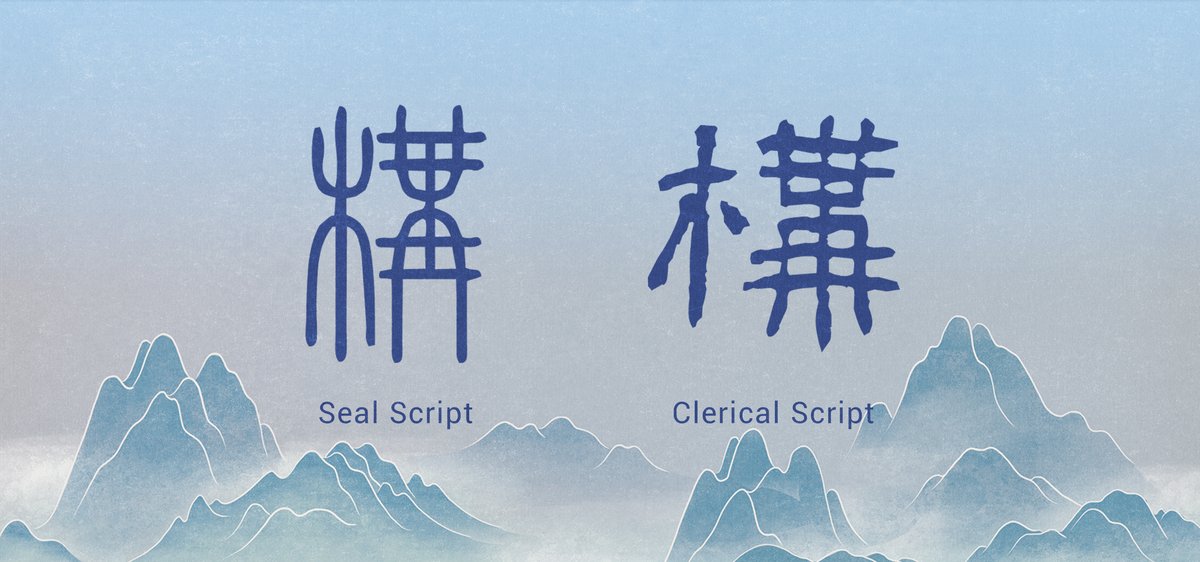

It’s perhaps no surprise then that the Chinese character for “build” or “construct,” 構 (gòu), is rooted in wood. Its earliest form, seen in seal script from around the first century BCE, features the wood radical, or 木 (mù), on the left, and 冓 (gòu) on the right—itself resembling interlocking wooden beams, and providing the character’s pronunciation. The traditional form of the character was later simplified to the 构 used on the Chinese mainland today.

In the Huainanzi (《淮南子》), a wide-ranging compendium on philosophy, politics, and science compiled in the second century BCE by Liu An (刘安), a Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) prince, and his court scholars, a description of prehistoric settlements appears to correspond with archaeological discoveries at Hemudu.

Learn more Chinese characters:

- 能: A Character Capable of Anything

- 游: Learn the Chinese Character for Journeys and Adventures

- 育: The Character That Follows You From Birth

“In ancient times, the people dwelt in marshes and nested in caves,” Liu writes. “In winter, they could not endure the frost, snow, fog, and dew; in summer, they suffered from the sweltering heat and swarms of mosquitoes and gnats. Then the sages arose, building structures of earth and wood to create houses (筑土构木,以为宫室 zhùtǔ gòumù, yǐ wéi gōngshì)—with beams above and eaves below—to shelter them from wind and rain, to shield them from cold and heat, and thus the people found peace.”

In modern Chinese, 构 is commonly used in phrases involving both literal and abstract concepts. One example is 构成 (gòuchéng), meaning “to form” or “to make up,” for instance: 山水和人家,共同构成了美丽的乡村。(Shānshuǐ hé rénjiā, gòngtóng gòuchéngle měilì de xiāngcūn. Mountains, rivers, and households together form the beautiful countryside.) Then there’s 构造 (gòuzào), meaning “structure” or “to construct,” and functions as both a noun and a verb to emphasize the process or mechanism of formation. For example, 地质构造 (dìzhì gòuzào) describes geological formations. The verb 构建 (gòujiàn) typically refers to building abstract things, such as “building a network (构建网络 gòujiàn wǎngluò),” while 构筑 (gòuzhù) can apply to both concrete and abstract constructions, for example, a city wall (构筑城墙 gòuzhù chéngqiáng) or a system (构筑体系 gòuzhù tǐxì).

In more abstract terms, 结构 (jiégòu) denotes the static structural relationships between components, as in 建筑结构 (jiànzhù jiégòu, architectural structure) and 社会结构 (shèhuì jiégòu, social structure). A related word, 构架 (gòujià, framework), refers specifically to a system intended to fulfill certain functions, such as 故事构架 (gùshi gòujià, narrative framework) and 组织构架 (zǔzhī gòujià, organizational framework).

In a challenge to all the above, the concept of deconstruction—proposed by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in the 1960s as a method of analyzing ideas, texts, or systems to show that meaning is not fixed or absolute—was translated as 解构 (jiěgòu) when introduced into the Chinese-speaking world in the 1980s.

构 also extends beyond the physical world into the realm of imagination, playing a vital role in shaping ideas, visions, and new concepts. A novelist developing a story idea must 构思 (gòusī, conceive), while an artist arranging visual elements will first 构图 (gòutú, compose). Grand ideas can be expressed with 构想 (gòuxiǎng), meaning “vision,” such as conjuring a blueprint for innovative, eco-friendly, and more livable future cities: 设计师对未来城市的发展有一个宏伟的构想。 (Shèjìshī duì wèilái chéngshì de fāzhǎn yǒu yí gè hóngwěi de gòuxiǎng. The designer has a grand vision for the development of future cities.)

Work of an imaginary or fictional nature is 虚构 (xūgòu), literally a “virtual construct,” which you may recognize from disclaimers for books, movies, and TV shows: 情节纯属虚构。如有雷同,纯属巧合。(Qíngjié chúnshǔ xūgòu. Rú yǒu léitóng, chúnshǔ qiǎohé. Fictional content. Any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.)

Depending on who’s using it, 构 isn’t always constructive in a positive sense—it can also be used to fabricate. This is captured in the idiom 向壁虚构 (xiàngbì xūgòu), literally “facing a wall and fabricating something,” which was coined by Xu Shen (许慎) in the second century. In the preface to the Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》), the earliest known dictionary in the world compiled by Xu, he criticizes the academic fraud of his time, noting that many so-called scholars were all too willing to fabricate sources and explanations for Chinese characters—a practice he described with this idiom. His work aimed to correct this trend and restore characters to their original, intended meanings.

An even worse act of fabrication—framing or falsely accusing someone of a crime—is called 构陷 (gòuxiàn), which suggests malicious intent and deliberate scheming. For example, 他被人构陷,成了替罪羊。(Tā bèi rén gòuxiàn, chéngle tìzuìyáng. He was framed and became a scapegoat.)

But more importantly, as we’ve seen, the character 构 connects the physical and the conceptual, embodying our creative capacity to bring ideas into reality. Whether erecting buildings or shaping thoughts and art, 构 represents a fundamental building block in the construction and transformation of the world around us.

构: The Character That Brings Blueprints Into Reality is a story from our issue, “Urban Renewal.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.