China’s newest UNESCO site could hold the keys to a lost kingdom. Explore its destruction and how historians are reviving the Western Xia tombs.

In the 1930s, German pilot Wulf-Diether Graf zu Castell-Rüdenhausen captured a remarkable photograph over the Helan Mountains in Ningxia, China: clusters of white conical earthen mounds rising from the desolate plain. Initially mistaking them for termite mounds, Castell-Rüdenhausen published the image in his book Chinaflug, little expecting that what he had casually recorded was actually the royal necropolis of one of the most mysterious dynasties in Chinese history: the Xixia, or Western Xia.

Nearly a century later, during the 47th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee in Paris on July 11, 2025, the Xixia Imperial Tombs became the country’s 60th property on the World Heritage List. The site comprises nine imperial mausoleums, 271 subordinate tombs, 32 flood-control structures, a 50,000-square-meter ritual complex foundation, and over 7,000 cultural relics housed in the onsite museum—and could serve as the missing key to unlocking a lost civilization.

What we do know is that the multi-ethnic Western Xia dynasty was established in 1038 by Li Yuanhao (李元昊), leader of the Tangut people who inhabited northwestern China. Li’s subjects encompassed Tanguts, Han Chinese, Uighurs, Tibetans, and more. At its zenith, Western Xia territory spanned approximately 1 million square kilometers, covering much of present-day Ningxia, western Gansu, northeastern Qinghai, and western Inner Mongolia. The dynasty coexisted for nearly 200 years with the Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties in what is now modern Chinese territory, before it was conquered by the Mongol forces in 1227.

Read more about China’s mysterious northwest:

- Tracing the Tangut: How Genghis Khan Order the Extermination of an Empire

- Riddle of the Sands: The discovery of A Vanished Civilization on China’s Silk Road

- City of Angels: A Forgotten Silk Road Relic Sheds Light on Early Christianity in China

Imperial China maintained a tradition of compiling official histories for preceding dynasties. But while the imperial historians of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368) dutifully compiled the History of Song (《宋史》), History of Liao (《辽史》), and History of Jin (《金史》) after these respective empires fell, they ignored the Western Xia, making it absent from the 24 historic chronicles later historians recognized as canonical to imperial China.

According to Chen Xuefei, a lecturer at the School of Ethnic and Historical Studies at Ningxia University, the lack of historical material on the Western Xia is largely due to their particularly brutal annihilation by Mongol forces. According to existing records, the Western Xia put up a particularly fierce resistance to Mongol conquest, and it’s alleged that Genghis Khan himself had been killed by a poisoned arrow from a Western Xia soldier—and consequently, made his successor vow to take revenge.

“As [Western Xia] cities fell, Mongol troops engaged with massacres and systematic looting,” Chen tells TWOC. “Court records, genealogies, state archives...all perished in the flames.” When Toghto, historian and chancellor of the Yuan dynasty, inherited the task of compiling dynastic histories, he and his team found a dearth of primary sources on the Western Xia.

Additionally, Western Xia pledged allegiance to the Song, Liao, and Jin courts at various times as a diplomatic strategy for survival. This tributary status likely influenced later historians to exclude it from orthodox dynastic recognition. That’s perhaps why Yuan historians granted the Song, Liao, and Jin parallel imperial status while relegating Western Xia to annexes in their official histories of all three dynasties.

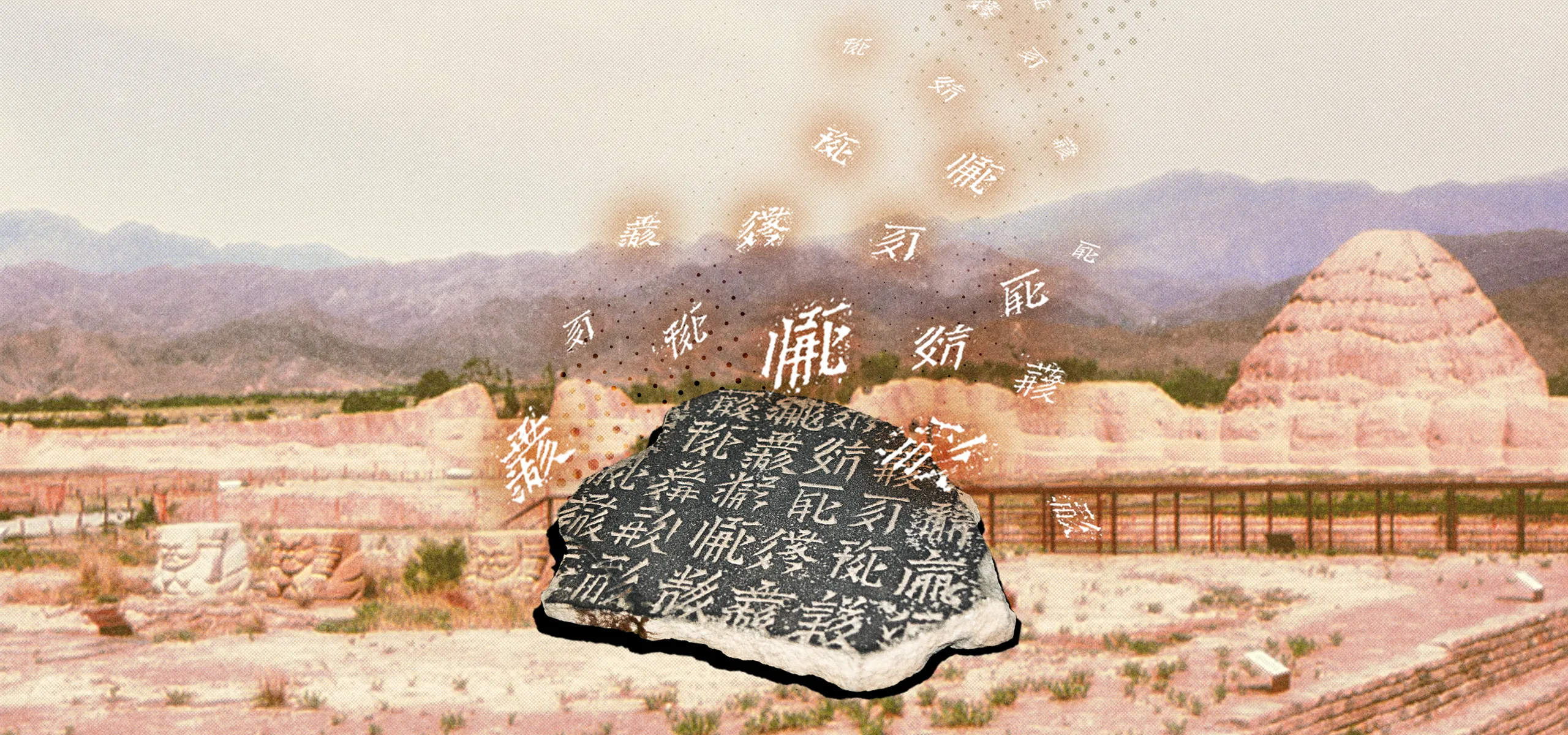

Given the lack of written records, archaeological work has become vital for learning about the dynasty’s history. The mausoleums, the largest, grandest, and best-preserved Western Xia archaeological site surviving today, were first explored in the winter of 1971 by a team led by Ningxia archaeologist Zhong Kan, before anyone guessed their connection to the Tangut empire. They discovered fragments of stone steles etched with mysterious script—square-shaped, like Chinese characters, yet distinctly alien-looking. Collecting these broken tablets, the archaeologists embarked on a needle-in-a-haystack investigation of their origins.

In the 2018 documentary Unveiling the Western Xia Mausoleums produced by China Central Television, Zhong later recalled having seen similar scripts on a fragment of Buddhist sutras unearthed a decade earlier. At that time, someone had suggested it might be Tangut script. A New Gazetteer of Ningxia from the Jiajing Era (《嘉靖宁夏新志》), a historical record dated to the 1400s, had also stated: “East of Helan stand several lofty mounds—the so-called Jia and Yu Mausoleums of the pseudo-Xia regime, modeled after the Song imperial tombs in Gongxian.” Both pointed to the mysterious Western Xia dynasty as the architects of these mounds.

In 1972, the Ningxia archaeological team launched formal archaeological fieldwork in the area. Based on their scale and distinctly shaped outer enclosures, researchers identified nine mausoleums as belonging to nine emperors among the hundreds of tombs, which matched the records of the History of Song. Yet attributing each mausoleum to an emperor remained elusive. Extensive Chinese and Tangut inscriptions have been found around the tombs, but most of them were severely—and seemingly deliberately—damaged.

“Whenever we looked at the inscriptions, the key information was always missing,” researcher Ma Shenglin noted in the documentary. “Where it should read ‘So-and-so Emperor,’ the characters identifying who were deliberately chiseled away.”

Some scholars attribute the devastation to troops stationed near the Helan Mountains by the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). Yet, A New Gazetteer of Ningxia from the Jiajing Era had mentioned earlier excavation attempts that had found “not a single artifact” within the tombs, indicating that systematic plundering must have occurred before the Ming.

Prominent archaeologist Niu Dasheng reached the following conclusion in a 1995 paper on the mausoleum: “These mausoleums were reduced to ruins during the Mongol conquest in 1226 and 1227, when Yuan Mongol nobles deployed troops for organized, large-scale excavation and destruction.”

Historical records state that Genghis Khan launched six invasions against the Western Xia from 1205 until its fall in 1227. Mongol forces repeatedly occupied the Helan Mountains and besieged the capital, Zhongxing prefecture (today’s Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia). The Annals of Xixia (《西夏纪》), written in the early 20th century by renowned historian Dai Xizhang (戴锡章), states that Mongol troops diverted rivers to flood the capital for six months during the 1209 invasion, collapsing buildings and “drowning countless residents.” Ming scholar Hu Ruli (胡汝砺) wrote the final Mongol campaign in 1226 and 1227: “[Xia subjects] dug tunnels to escape Mongol arrows—scarcely one in a hundred survived, their bones littering the wilderness.” Other historical records, including The Secret History of the Mongols (《蒙古秘史》), written 13 years post-conquest, and the 14th-century A Compendium of Chronicles (《史集》) by Rashid-Din Hamadani of the Ilkhanate, both record the execution of the last emperor Li Xian (李睍) and the massacre at Zhongxing.

Tomb raiders compounded the damage. Chen Xuefei tells TWOC that in the 1970s, archaeologists discovered three skeletons in a burial chamber. Based on forensic analysis and over evidence, they surmised that two looters likely entered the chamber, clashed over dividing the loot, and one murdered the other. While escaping with the plundered artifacts, the survivor was in turn murdered by his accomplices on the surface, who severed the rope and sent him crashing back to his death in the tomb.

Modern construction then finished the job. “Since the 20th century, construction projects around Yinchuan have salvaged bricks and tiles from surviving structures, and excavated rammed-earth walls and burial pagodas,” says Chen.

Without primary records and intact steles from the Western Xia mausoleums, deciphering the enigmatic Tangut script posed another major obstacle. According to the History of Song, before founding his empire, Li Yuanhao commissioned his minister Yeli Renrong (野利仁荣) to create a writing system based on Chinese character principles, creating nearly 6,000 characters for the Tangut language. They are notoriously complex symbols, with most requiring over ten strokes to write. But after the dynasty’s fall, this script faded into oblivion.

In the early 19th century, scholar Zhang Shu (张澍) discovered a long-sealed stele in Wuwei, Gansu—now known as the Stele of the Reconstructed Gantong Pagoda at Liangzhou’s Huguo Temple. One side of the stele bore unrecognizable characters resembling Chinese. Only after checking the dates from the Chinese inscription on the reverse did Zhang realize he had found surviving examples of Tangut script. Though this marked the modern rediscovery of the script, Zhang’s breakthrough received scant attention at the time.

In 1908 and 1909, Russian explorer Pyotr Kozlov’s expedition unearthed a trove of Western Xia artifacts at Khara-Khoto—an abandoned Xixia city, also known as Heishui city, in what is now western Inner Mongolia—and brought them to Russia. Among those artifacts was the Pearl in the Palm: A Tangut-Chinese Lexicon, which was compiled by Tangut scholar Gule Maocai (骨勒茂才), containing 1,504 unique Tangut characters. In 1912, Chinese scholar Luo Zhenyu met Petersburg University professor Aleksei Ivanovich Ivanov in Japan and saw a single page of the lexicon. Recognizing its value, Luo borrowed nine pages to photograph—thus introducing the text to Chinese academia for the first time. When Ivanov visited Tianjin in 1922, Luo borrowed photographs of the entire book and commissioned his son, Luo Fucheng, to transcribe and collate the manuscript. Published in 1924, this edition became the foundation for deciphering Tangut script.

By the 1970s, when archaeological excavations began at the Western Xia mausoleums, barely anyone in China could decipher the Tangut script other than Luo Fucheng and his brother Luo Fuyi, according to People Weekly magazine. It fell to Li Fanwen, then a logistical staff member of the Ningxia archaeological team and a Tangut enthusiast, to travel to Beijing in 1973 carrying over 30,000 Tangut character cards transcribed from the site to seek help from Luo Fuyi.

Finally, in 1974, Li reassembled a Tangut inscription from fragmented stele pieces at Mausoleum No. 7 and deciphered the 16 characters as “Epitaph for the Mausoleum of the Emperor of Sacred Virtue and Ultimate Excellence, Protector of the Great White and Lofty State.” This confirmed Mausoleum No. 7 as the resting place of Emperor Renxiao, the fifth ruler of Western Xia—still the only positively identified imperial tomb in the necropolis. Li continued his research and published the world’s first fully-structured Tangut-Chinese Dictionary in 1997.

In 2005, Li, together with over a dozen scholars, completed the Comprehensive History of Western Xia, meticulously tracing the Tangut people’s journey from the emergence of their tribe to their diasporic migrations after their empire’s collapse, filling the gap in the “Twenty-Four Histories” where a Western Xia history should have been. Archaeologists have continued working on the site since the 1970s, and the number of identified tombs has risen to 271 in 2015, though many identifications remain controversial. Popular interest in western China’s lost empire also rose, with various bestselling books and documentaries released over the last decade expounding on Western Xia’s mysterious rise and fall, and archaeologists search for answers.

Many questions remain: The resting places of the last three Western Xia emperors are unknown—possibly never constructed or deliberately destroyed. The task of identifying each tomb occupant continues, and we still know little about the logic behind the site’s layout and structure, the relationship between emperors and others buried on the site, and countless other details about daily life in the Western Xia and the reason behind its total annihilation. Though the UNESCO site is now known to the whole world, it may not be ready to give up all its secrets yet.

Vanished Empire: Resurrecting China’s Western Xia Tombs is a story from our issue, “Urban Renewal.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.