How an ancient teacher’s hometown becomes a holy city that attracts rulers and common people alike for over two millennia

By 7:30 in the morning, hundreds of visitors, many clad in traditional scholars’ attire, crowd the southern gate of Qufu’s centuries-old city wall. Locals seize the opportunity to sell breakfast, souvenirs, and guide services, calling out to them as laoshi (老师)—a respectful term to address adults today that evolved from its original meaning of “teacher” or “master.”

As 8 o’clock approaches, visitors fuss with their costumes and jockey for the best vantage point to watch and film the “gate-opening ceremony,” which will sweep them through the city wall and into the Confucius Temple, the sprawling complex celebrating the legendary teacher whose influence still shapes Chinese society today.

Read more about Confucius and Confucianism in China:

For over two millennia, people from across China and around the world have made pilgrimages to Qufu, a county-level city in Shandong province, often dubbed the “Holy City of the East (东方圣城).”

Throughout history, 12 emperors have made imperial visits to the sage’s hometown to demonstrate their reverence for Confucianism in governing the country. In 1684, the Emperor Kangxi of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), for instance, made a formal visit to the Confucius Temple, kowtowing and offering sacrifices to the sage’s statue at the Dacheng Hall, the focal point of the complex. He also inscribed a plaque reading 万世师表 (“the Sacred Model for Ten Thousand Generations”), a term used to praise Confucius in the 3rd-century historical text The Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》). He then ordered the plaque to be hung in the main hall as well as in other Confucius temples that had been established across the country since at least the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). His grandson, Emperor Qianlong, not only upheld the tradition but also traveled to Qufu eight times—more than any other ruler since Emperor Gaozu of the Han, who first visited in the second century BCE.

Although the later Qing emperors never visited Qufu, they paid their respects to Confucius at the Confucius Temple in Beijing—the second largest after the Qufu temple—and inscribed plaques with various honors, such as Emperor Yongzheng’s “Sage Never Ever Seen in History (生民未有).”

The Confucius Temple in Qufu is said to have been built in 478 BCE, the year after the sage’s death, on the site of his original three-room house, by order of the ruler of the Lu State. Since then, it has been expanded and renovated into a vast 460-plus-room complex, making it the country’s second-largest surviving ancient complex, after Beijing’s Imperial Palace. Legend has it that the 28 stone pillars around Dacheng Hall—some engraved with dragons, symbols of imperial power in ancient China—were so exquisite that Confucius’s descendants had to cover them with red silk during Qianlong’s visits, fearing the emperor’s anger or envy.

In addition to its centuries-old architecture and décor, the site features thousands of trees—some over 2,000 years old—steles that record major renovations and showcase calligraphy from different eras, as well as remnants of Confucius’s life, such as the famous Apricot Altar, where he taught his disciples.

Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, the Confucius Temple, together with the neighboring Confucius Mansion and Confucius Cemetery—collectively known as the “San Kong” or “Three Kong” sites—continues to attract visitors even in modern times. Tourism in the small city, home to around 610,000 people, has flourished over the past decade with the emergence of the “New San Kong,” including the Nishan Sacred Land, the Confucius Museum, and the Confucius Research Institute. In the first five months of this year alone, the city welcomed over 5.6 million visitors and generated more than 5 billion yuan in tourism revenue.

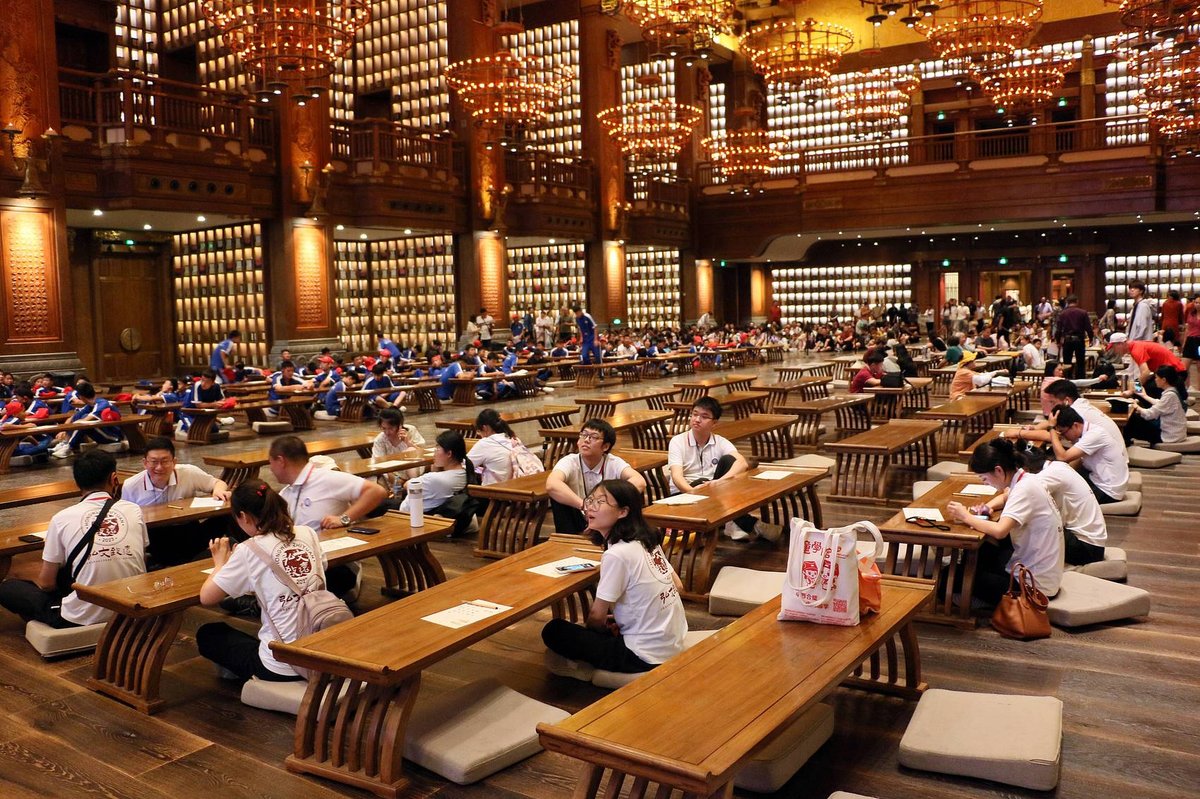

Opened in 2018, the Nishan Sacred Land is a Confucian cultural experience center built on Nishan Hill, the sage’s birthplace. It has gained popularity for its night tours, featuring light shows, night markets, drone performances, and “study tour” programs where visitors can explore Confucianism and traditional culture—from The Analects (《论语》) and ancient rituals like the “First Writing Ceremonies” to the “six arts” (六艺) that students once aimed to master.

“When we first started [several years ago], we organized Qufu study tours once or twice a week, but now the program accommodates up to four groups weekly, each with 200 to over 1,000 participants,” Zhou Lu, a study tour facilitator, told local newspaper Qilu Evening News last June. According to him, Qufu’s study-tour routes have become increasingly diverse in recent years, blending scenic beauty, hands-on experiences, and cultural learning to fully spark students’ curiosity.

The great educator would surely be pleased to see his old home put to such use. After all, he has advocated for over 2,000 years: teaching students in accordance with their aptitudes (因材施教).