A cursory look back through some key characters in China’s history reveals that much can be achieved, even in one’s twilight years

China’s renowned modern-day writer Eileen Chang once famously declared in the preface to her essay collection Legend (《传奇》): “Better get famous before you get old.” She was just 24 when the book was published. Yet, fortunately for those not lucky enough not to be born prodigies, Chinese culture equally celebrates figures who achieved greatness later in life. Across dynasties, from emperors and ministers to generals and scholars, a plethora of remarkable personalities emerged from once-unremarkable youths. The third-century warlord Cao Cao (曹操) captured this spirit in his poem “Though the Tortoise Lives Long (《龟虽寿》),” writing: “An old warhorse may be stabled, yet still it longs to gallop a thousand miles. A hero in his twilight years never abandons his ambitions.” These lines would become an anthem for generations of late achievers, reminding us that it’s never too late to pursue one’s dreams. Below, we delve into just a few such examples from throughout Chinese history.

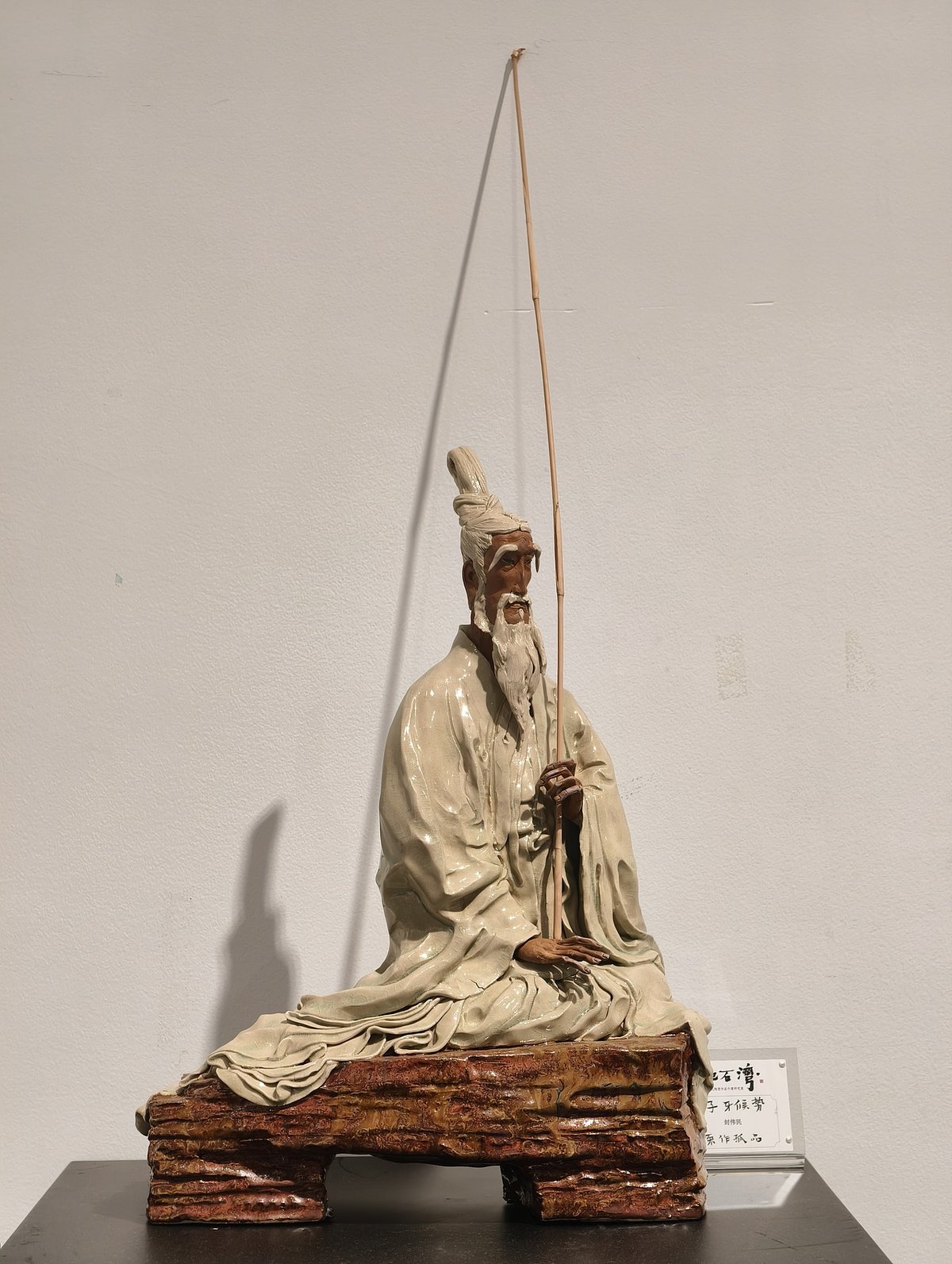

Jiang Ziya: A latent talent who met his lord in his 70s

Jiang Ziya (姜子牙), born in the late Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE), can be regarded as one of ancient China’s earliest and most renowned politicians, strategists, and military thinkers. He laid the foundation for the 800-year Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE) and was recognized by religious, military, and political leaders as a master of their teachings.

However, it was only by luck that this legendary man achieved real-world renown in his golden years. According to Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) by Han-dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) historian Sima Qian (司马迁), Jiang endured decades of hardship in his youth. Though talented and ambitious, he remained unrecognized, working as a butcher and running a wine shop in the Shang capital without any opportunity to realize his political aspirations.

Jiang’s fortunes didn’t begin to turn until a chance meeting by the Wei River, where he crossed paths with Ji Chang (姬昌), the future King Wen of Zhou. The two connected instantly, and impressed by Jiang’s wisdom, Ji appointed him Grand Tutor. Vivid details of this meeting would be embellished in various literary works of subsequent dynasties. For example, in the Yuan-dynasty (1206 – 1368) storyteller’s script, The Story of King Wu’s Expedition Against King Zhou (《武王伐纣平话》), it was claimed Jiang initially caught Ji’s attention because he was fishing with a straight hook and no bait, giving rise to the saying: “When Lord Jiang fishes, there are always those willing to take the bait.”—a metaphor for how fate will eventually take its course.

In the following years, Jiang displayed remarkable political and military prowess. He assisted Ji Chang in implementing “benevolent governance” and strengthening the Zhou state. After Ji Chang’s death, he continued to serve his son, Ji Fa (姬发), who became King Wu of Zhou. In 1046 BCE, Jiang, then in his 80s, commanded the Zhou army to a decisive victory against the Shang at the Battle of Muye, overthrowing the dynasty. After the establishment of the Zhou dynasty, Jiang was appointed ruler of the eastern Qi state (present-day southern Henan and Shandong). Rather than imposing the Zhou rites by force, Jiang respected local traditions while developing the salt and fishing industries, taking advantage of Qi’s coastal position, and promoting commerce—quickly turning Qi into a formidable power.

To this day, Jiang’s story continues to be told in novels, films, and television series, and was most notably immortalized as a divine figure in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) classical novel, “ Investiture of the Gods (《封神演义》).”

Baili Xi: The “Minister of Five Sheepskins”

Compared to Jiang Ziya, who eventually hauled himself out of anonymity via an eccentric fishing technique, Baili Xi (百里奚) from the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE) took an even more arduous path until similarly achieving prominence in his 70s.

According to Records of the Grand Historian, Baili Xi was originally from the state of Yu (in present-day Shanxi province). Born into poverty, he traveled through various states seeking opportunities to realize his ambitions. During his journeys, he met the virtuous Jian Shu (蹇叔), and the two became close friends. With Jian’s recommendation, Baili returned to Yu and served as a senior official. However, his newfound authority took a dramatic turn for the worse when, in 655 BCE, Yu was conquered by the state of Jin, and Baili was captured along with the heads of state. The Jin later sent Baili to the Qin state as part of a dowry of servants, but he escaped during transport and fled to the state of Chu, where he was forced to work as a cattle herder.

Explore the political world of ancient China:

- How Prophecies Were Key to Maintaining Power in Ancient China

- Ancient Snitches: How China’s Emperors Encouraged Informants

- Strangest Laws from Ancient China

By this time, Baili was already over 70 years old. The turning point came when Duke Mu of Qin, eager to recruit talent, learned of Baili’s abilities and ransomed him from Chu for five black sheepskins and appointed him as a senior minister. Fittingly, this earned Baili the nickname “Minister of Five Sheepskins.”

Once again in power, Baili recommended his friend Jian Shu for the title of duke, and together they assisted Duke Mu in implementing a series of reforms: improving domestic governance and agricultural production, skillfully handling diplomacy with the Jin, and gradually subduing the western regions. Under Baili’s guidance, the Qin transformed from a peripheral state into a powerful kingdom, laying the foundation for the eventual unification of China centuries later.

Chong’er: The hegemon who endured 19 years of exile

Duke Wen of Jin, Chong’er (重耳), was the 22nd ruler of the state of Jin during the Spring and Autumn period. Recognized as one of the “Five Hegemons” of the era, his path to power was remarkably late—after 19 years of exile, he did not ascend the throne until the ripe age of 62.

As a son of Duke Xian of Jin, Chong’er likely lived a life of comfort. However, in 656 BCE, a palace conspiracy irrevocably altered his fate. At that time, Duke Xian’s favored consort schemed to secure the succession of power for her own son. She falsely accused the Crown Prince of attempting to poison the duke, driving him to suicide. She then implicated Chong’er and another prince in the plot. To protect himself, the 43-year-old Chong’er was forced to flee the Jin, beginning his prolonged exile.

The Commentary of Zuo (《左传》), a historical text complied in the Spring and Autumn period by historian Zuo Qiuming (左丘明), provides detailed records of Chong’er’s wanderings: in his self-exile he sought refuge in eight different states: Di, Wei, Qi, Cao, Song, Zheng, Chu, and Qin, via a journey that was marked by hardship and humiliation—in the state of Wei, he was reduced to begging a farmer for food; in the Cao, the duke of the state spied on him while he bathed, curious to prove a rumor that his ribs were fused; and in the Zheng, a senior minister advised the state’s ruler to execute Chong’er to eliminate any future threat. However, his greatest test came in the state of Qi. Once there, Duke Huan of Qi treated him generously, marrying him to a woman from the Qi’s ruling clan. Immersed in the comforts of a luxurious life, Chong’er gradually lost his ambition and decided to remain in Qi indefinitely. Noticing this, his wife conspired with his followers, got him drunk, and transferred him away under the cover of darkness.

Finally, in 636 BCE, with the military support of his Qin allies, Chong’er returned to the Jin state and assumed the throne. By then, Chong’er was 62 and had spent nearly two decades away. As Duke Wen of Jin, he dedicated himself to strengthening his state, implementing internal reforms, and building up its military.

After being decorated for meritorious service by supporting the royal house during a rebellion in the Zhou court, and he and his forces achieved a decisive victory over the powerful state of Chu at the Battle of Chengpu, the Zhou King formally recognized Chong’er as the leader of the feudal lords, ushering in a century of Jin hegemony.

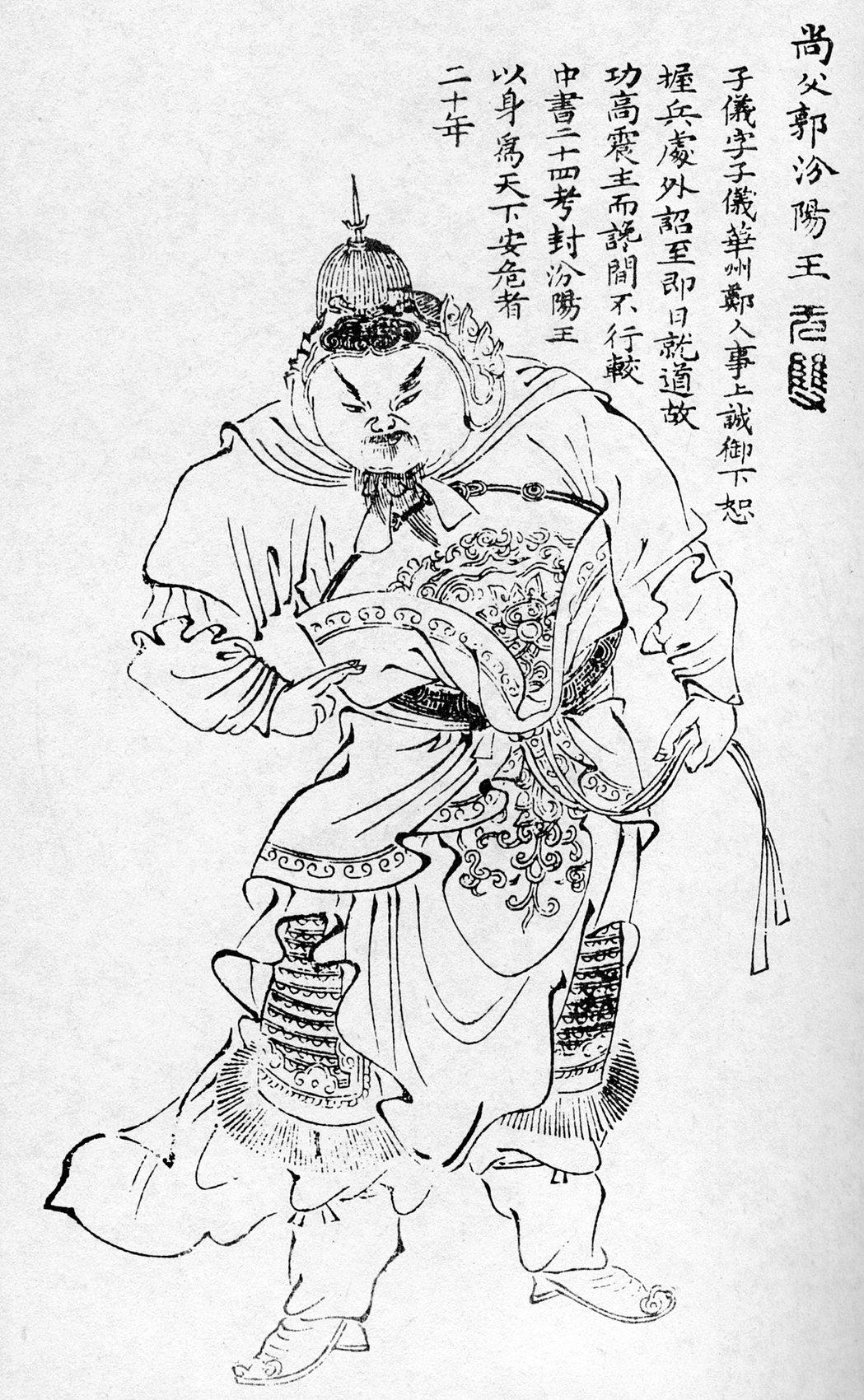

Guo Ziyi: The savior of the Tang dynasty

In 755, the An Lushan Rebellion nearly brought the glorious Tang dynasty (618 – 907) to its end. During the uprising, rebel forces swept through China’s heartland and captured both capital cities—Chang’an and Luoyang. Emperor Xuanzong fled the latter in disarray, and the empire teetered on the brink of collapse. At this critical moment, Guo Ziyi (郭子仪), a 58-year-old military commander, stepped into the spotlight.

Though Guo came from a family of officials and had served in the army for decades, he had yet to win any notable battles. The outbreak of the rebellion, however, thrust him into a central role. Appointed as the military governor of Shuofang, he was tasked with suppressing the rebellion. According to the Old Book of Tang (《旧唐书》), Guo achieved a series of remarkable victories: in 757, he commanded Tang forces to a decisive triumph at the Battle of Xiangjisi, reclaiming Chang’an, and soon afterward recaptured Luoyang. The recovery of the two capitals revitalized the morale of the Tang forces and marked a turning point in the war.

By 763, the eight-year-long rebellion was finally suppressed. But another crisis immediately followed: the Tubo Kingdom seized on the Tang’s reduced strength to invade, occupying Chang’an once again. Now aged 66, Guo was to prove himself more. Employing numerous ingenious stratagems to mislead the enemy, he defeated a larger Tubo force and retook the capital for the second time. Then in 765, when Tubo allied with the Uighurs to launch a massive invasion, Guo, nearing 70, rode alone into the enemy camp, where he successfully persuaded the Uighurs to switch sides and join the Tang in repelling Tubo.

What makes Guo’s career even more enviable is that with his extraordinary wisdom, he served under seven successive emperors, navigating intricate court politics and almost never falling from favor. He eventually died of natural causes at the age of 85—a rare example of a general whose monumental achievements eclipsed even those of his rulers, yet managed to safeguard his standing and life to the very end.

Su Xun: The literary master who began studying at 27

In an era where most Chinese scholars began their education in early childhood, Su Xun (苏洵) stood apart as a remarkable exception. This Song-dynasty (960 – 1279) literary master, later counted among the “Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song dynasties (唐宋八大家),” only began applying himself to serious study at the advanced age of 27. Nevertheless, he would go on to become one of the most celebrated literary figures of his time.

Born into an official family in Sichuan, Su showed little interest in learning in his youth, as evidenced in an epitaph written for him by one of his contemporaries and most influential literary masters of the time, Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修), who described how even into adulthood, Su remained unlearned. That is, until the age of 27, when inspired by his elder brother’s success in the imperial examinations, Su finally began immersing himself in books.

But his path to erudition was not smooth. After repeatedly failing the imperial examinations, Su made a crucial decision: to abandon the pursuit of passing and instead devote himself to studying classical texts and statecraft. He burned his earlier writings and, for over a decade, immersed himself in reading a broad range of material, gradually developing his distinctive, powerful, and logical prose style.

In 1056, the 47-year-old Su would travel to the capital Bianjing (modern-day Kaifeng) with his two sons. His essays, including “On Current Policies (《几策》),” “On Power (《权书》),” and “On Strategy (《论衡》),” immediately caused a sensation in literary and political circles. Ouyang Xiu was deeply impressed by Su’s essays and recommended him highly to the imperial court. Su’s reputation spread rapidly. Even more remarkably, his sons Su Shi (苏轼) and Su Zhe (苏辙) both passed the highest-level imperial examinations that same year. Their remarkable talents would also earn them the court’s commendations and place them alongside their father in the “Eight Great Prose Masters”—an unprecedented literary trio in Chinese history. Though Su Xun never achieved an official rank through examinations, his literary accomplishments and success in educating his sons created an enduring legacy.

Ironically, Su Xun’s story was later immortalized in the Southern Song primer Three Character Classic (《三字经》) as both a tale of inspiration and caution, writing: “Su Laoquan (Su Xun’s nickname) was 27 when he finally devoted himself to study. Already old, he regretted his delay. You young students should reflect early.” This lesson suggests that while Chinese culture celebrates late bloomers, it also values early dedication—achievement may come later, but earnest effort should never be delayed.