Cheng Huizi tells a story of regrets and growth brought by the college entrance exam

It is usually around Xiaoman, which is the eighth term in the traditional solar calendar, coming around the middle of May, that the rains assault the Lingnan region. Rain in that season is often overwhelming and violent. This is the time when dragon boat races take place, so people call these the “dragon boat rains.” The dragon boat rains come quickly, without much warning. They soak the world below with streams of water as thick as a hemp cord. Anyone walking on the street, even if they have an umbrella, will find themselves drenched. The vegetation slurps up the water and grows like crazy, becoming thick and lush overnight. The downpour usually only lasts half a day before the clouds break, allowing the shining white sun to peek through, warming up those drenched pedestrians and steaming a vicious humidity out of the ground below.

In Lingnan, people often say: To children, the dragon-boat rains are the immortals draining their bathtub. Children are innocent. They don’t mind the humidity. The heavy rains are an excuse to play. All they care about is having fun in the water. To those a little bit older, on the verge of adulthood, however, the rains are unwelcome. The torrential downpour rakes the eaves and adds to their problems. The rains come, after all, at the same time as a major event in life: the college entrance exam.

A month before the exam, Liangliang told me, “Teacher, I can’t sleep.” After quitting my job, I became a private tutor and Liangliang was my student. She was in her final year of high school. I asked if it was the entrance exam that brought on her insomnia. She thought for a moment and said she didn’t think so. At first, she suspected mosquitoes, since they were buzzing in her ears in the middle of the night, but her family put up a mosquito net and gave her a pair of electric mosquito repellent boxes. Later, she decided that maybe it was the heat keeping her up, but cranking up the air conditioning couldn’t alleviate the lingering feeling in her chest. They bought her an electric fan with a cooling function and she left it blowing on low power against herself.

Eventually, she blamed her insomnia on her pillow. The buckwheat pillow, reliable for so many years, suddenly gave her neck pain, left her dizzy the next day, and kept her awake all night. Her family went out and bought a latex pillow from Thailand, wrapped in a silk cover. Liangliang’s mother secretly put an amulet that she had collected at a temple under her bed, hoping that it would help her sleep.

After all that, Liangliang still appeared in the morning class with black circles under her eyes. She said that the sound of the dragon boat rain had kept her awake. Without speaking, I pulled out her stool and sat beside her while she yawned and sipped her coffee. We talked for a while about her schoolwork; then she rested her chin on her hand and admitted feebly that perhaps her insomnia was because of the exam.

How should I describe my mood when I heard her say that? At first, it struck me as peculiar and amusing, but I also understood this anxiety that strikes young people. It has been around ten years since I took the college entrance exam, and I am now almost ashamed to talk about those distant memories. People who have already been through the college entrance exam can say that it is only a small hill compared to the peaks that one will eventually have to scale in life. Compared to the frustrations, setbacks, tough times, and unexpected situations to come, the exam is scarcely worth mentioning. I admit this is true—but it is disgraceful to treat these matters with the cruelty and arrogance that is only possible once one has gotten through them. Who among us didn’t sleep at eighteen years old on a pillow of tangled-up dreams?

I didn’t talk to Liangliang about my own experience preparing for the exam, but instead told her what happened afterward. After my results came, my mother and I took a vacation to Xiamen, Fujian province, to relax. We took two other mother-and-daughter pairs with us. The three mothers were the same age and acquainted with each other. Their daughters were of different ages. One girl was a sophomore at university and the other was in middle school. I expected to do well on the exam and get into Peking University, but I ended up six points short.

Looking back at twenty-seven years old, I realize that this isn’t a poor result, it was actually quite outstanding, but at eighteen, I could not free myself of regret over those six points. On the trip, while everyone napped on the bus, I was pressed against the window, sobbing. Listening to the waves lapping on the reef, and walking through Gulangyu Island, alive with color, I felt that I was the unluckiest person in the world.

The older girl who went on the trip with us was studying information technology at a decent school selected for sponsorship and improvement under the government’s Project 211; the younger girl was still years away from her exam. I didn’t want to show anyone that I was unhappy with my result, since I thought they would suspect me of putting on a show out of pride. I forced a smile throughout the entire trip, absorbing against my will all the kind words of well-wishers. Still, in a secret corner of my heart, I was going over the results, considering that if I had not blown two multiple-choice or one long-answer question, the result would have been different. It was hot and humid that summer in Fujian, but a cool wind blew off the sea at dusk; the evening breeze dispelled the mugginess of the day, but it could not touch my disappointment. My heavy heart was like the reef, full of the crabs of regret.

As far as my eyes could see was magnificent scenery, with the ocean meeting the sky. It seemed empty to me, though, meaningless, and completely unenjoyable. It was too vapid to make up for those six points.

For a time, I made up my mind to retake the test, but I finally gave in to my teachers, family, and friends’ persuasions to give it up. Carrying a secret anguish and defiance with me, I went to Nanjing University. I decided that the rest of my life would be marked by compromise and cynicism. Unexpectedly, however, four years in Nanjing reshaped my value system, let me walk out of the shadow of the exam, find my interests, and stop worrying about a point or two dragged out of the examination machine.

Nanjing University promoted a composed, scholarly atmosphere. Even the flora and fauna on the campus have a gentle and magnanimous temperament. Relationships between students were friendly. Teachers never put their charges under too much pressure. This made my four years at the school go by relatively smoothly. When I went to Peking University for graduate school, I looked back fondly on the cozy library, delicious iron pan rice, and even the days of going to class and studying with friends. When I told Liangliang all of this, she was not convinced. “Nanjing University is a pretty good school,” she said, “and you ended up going to Peking University eventually. If it didn’t turn out like that, would you still be able to get over the exam so easily?”

Her question was reasonable. I had thought about it before. If I hadn’t gone to Peking University for graduate school, would I have ended up regretting my time at Nanjing University? I don’t think so. When it came time to choose a graduate program, going to Peking University was no longer particularly important to me. I knew that there were other choices available. That proved that my years at school were not wasted. Unlike in middle school, at university, I realized, as did many other students, that I didn’t need to repeat my youth when I had put so much pressure on myself only to check the right boxes on an exam paper. I could begin to explore more possibilities for myself—and even if they were limited, they were more important than six points on an exam.

It was not that my university years were spent trying to deal with the regrets of my college entrance exam, but rather that I had the time to let those wounds heal. One day, the thought of my disappointment occurred to me; it had been so long since I had recalled those regrets that I realized I had moved on. The wounds may have left scars behind, but the four years of reading and writing in Nanjing opened up a brighter landscape, so I was sure that there would be no lingering pain.

The dragon boat rain stopped at noon. Outside the window, the sky slowly brightened. Liangliang’s expression was a mixture of belief and disbelief. She was earnest but adorable. I told her that no matter what she scored, no matter what school she went to, she would regret it, even if she must take it as good fortune. There is no way for us to take all the roads available to us, I told her. We will always have regrets. Is it worth losing sleep over them?

Liangliang had narrow, long eyes, and when she was unhappy, her eyelids drooped across them. As class came to an end and I got up to put on my shoes, she stopped me to ask, “If I don’t do well on the test, is there a chance I won’t be able to make things right?”

“No,” I said, “you will have many chances.”

“If I don’t get a good score and I can’t go to grad school,” she asked, “I’ll have a mediocre life, won’t I?”

I thought about this for a moment. “Actually,” I said, “Most people live mediocre lives.”

Liangliang glanced up at me. Her expression was soppy. She unconsciously reached out to pat the reed-wrapped rice dumpling hanging from the light switch cord (this was one of her mother’s ideas, since the Chinese word for this type of dumpling sounds like the word for “getting into a top school”), perhaps trying to break the uncomfortable, expectant mood. “I’m worried that I won’t do well on the test. If I can’t get a good score, will you look down on me secretly?”

Standing there on the threshold, these juvenile words almost made me laugh. Twenty-seven-year-old me would never have used that tone or phrase, but I suppose I would have at eighteen. I used to toss and turn the same way in bed at night, and to go around uneasily during the day, with the same desire to speak my true feelings. I imagined her as I was at eighteen. I took her hand. “Don’t worry,” I said, “you’ll do fine.”

The next three days were a mix of torrential rain and sunshine, with black clouds over the city one moment and clear skies the next. Liangliang, and countless other Liangliangs, were all hard at work in exam rooms. The exam would determine their fate. The exam would have no bearing on their fate.

Three days later, the evening after the exams were done, the storm clouds raced away and the sky was piled high with magnificent sunset clouds, dense cumulus streaked purple and red by the rain, joining the waves at the end of the road. The summer breezes finally ended their long journey; the humidity that swirled around the ground for so many days was gently swept away.

I sent a WeChat message to Liangliang: “Congratulations on entering the world of adults. Don’t waste the evening breeze.”

Author’s Note:

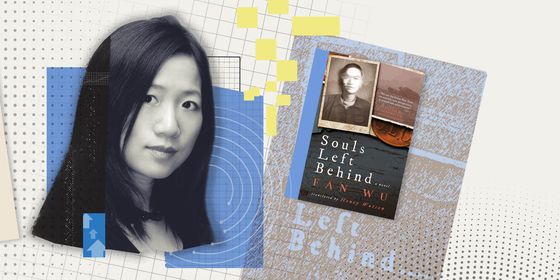

The college entrance exam, or gaokao, should have faded in my memory, with almost a decade having passed, but my student reminded me of the very event. My old obsessions finally became stories that can comfort others. This story is by no means a reconciliation with the experience: Only those who experienced it can understand the subtle melancholy and the sadness of growth behind the story.