Fan Wu’s latest historical fiction chronicles the often-ignored hardships experienced by Chinese laborers sent to Europe during WWI

China’s Qingming festival (sometimes called Tomb-Sweeping Day) is little known in most of the West. But the people of Noyelles-sur-Mer, a quaint town of 700 people in northern France, are well acquainted with it. They have held ceremonies for the festival each year since 2002 to acknowledge a once-forgotten group of people laid to rest in their town’s cemetery: 841 Chinese laborers who died in Europe during the First World War.

In most history books, China is not considered a major participant in World War One. The country didn’t declare war against Germany until 1917, three years after the war broke out, and never sent troops to the frontlines. Instead, they sent the Chinese Labor Corps—over 140,000 workers—who built airfields, repaired railways, and dug trenches to aid the Allied war effort. This is the historical backdrop for Fan Wu’s fictional story of a Chinese laborer in France who stays in the country and builds a life there long after the armistice in 1918.

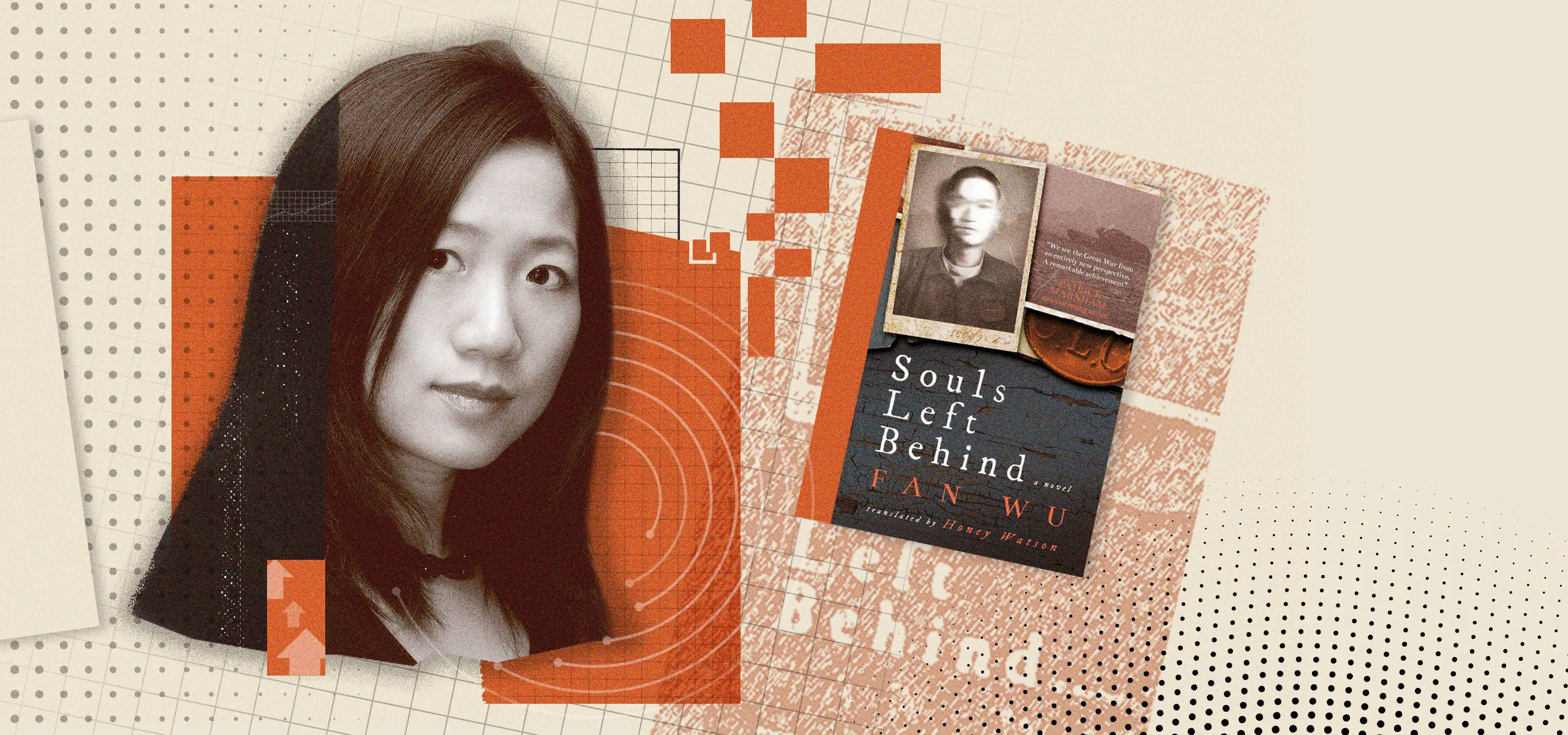

Through Zhang Delun’s story (he later changes his first name to David when he settles in France) Souls Left Behind highlights the overlooked contribution of Chinese workers to the Allied victory. It’s an important narrative, praised by renowned Chinese author Feng Jicai for “restoring and reflecting on history…showcasing the unique and unimaginable destinies of these ‘small players.’” Originally published in Chinese in 2023, the book has a high score of 9.6 on popular review platform Douban, though admittedly from only 14 reviewers.

Though Souls is a work of fiction, its characters and their plots echo the real history of the Chinese Labor Corps. The story starts in early 1917, with people in China debating joining the Allies. Many hoped that if China helped them win the war, it would give the country a stronger voice on the global stage and help the country renegotiate the despised “unequal treaties” that gifted Chinese territory and special rights to foreign countries, most egregiously to Japan, which was encroaching ever deeper into Manchuria.

Zhang is a well-educated young man from one of the wealthiest families in his hometown. He is set to inherit the family tea business and live a comfortable life. However, when his parents arrange for him to marry Miss Lu, the daughter of a wealthy local family (Lu’s feet are still bound), Zhang feels trapped in this old-fashioned life and flees on his wedding night. When he hears young students discussing heading to Europe to learn new ideas and technology to bring back to China, Zhang sees a chance for him to break free of his mundane life and make some money (one French franc per day).

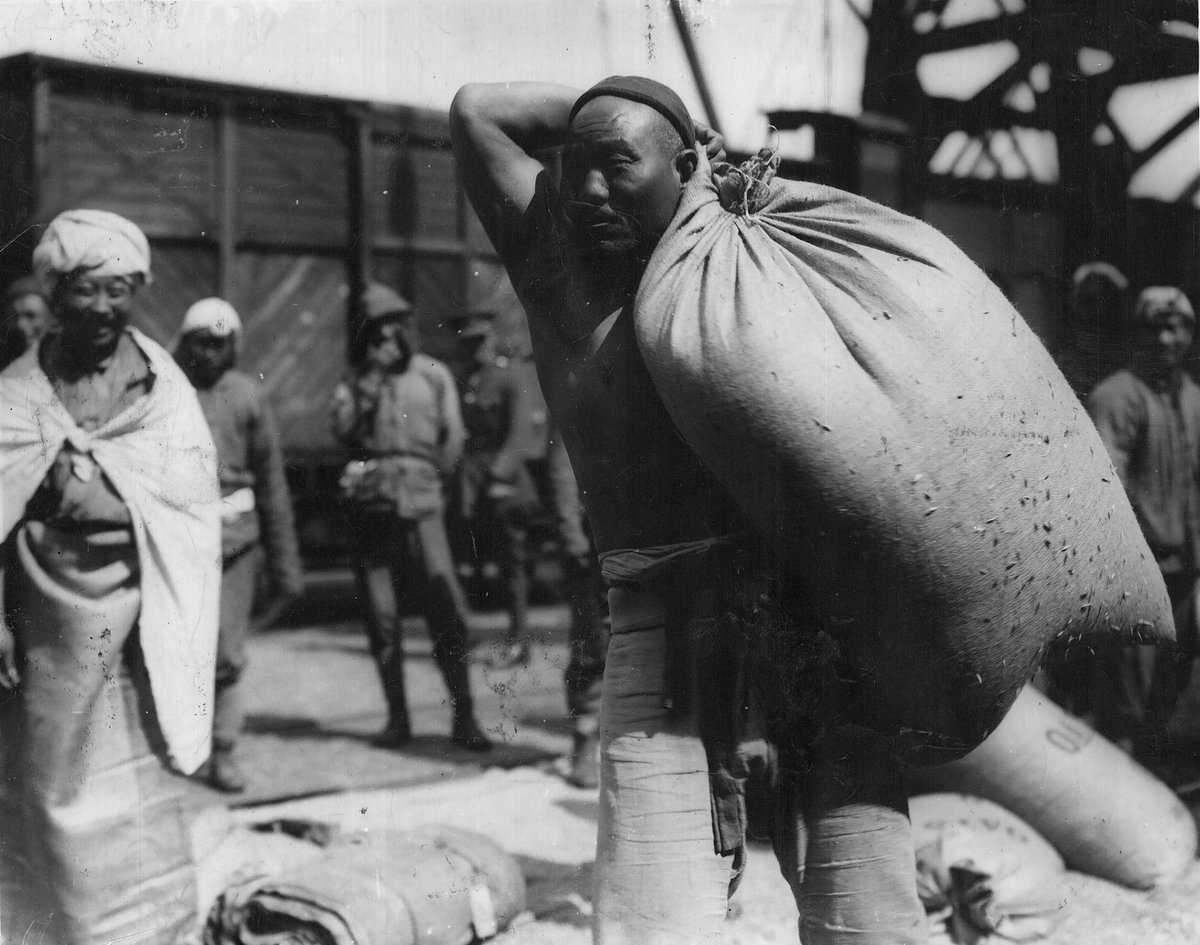

Once Zhang leaves China, however, he finds mostly hardship. He spends days in the cargo hold of a ship bound for Vancouver, rides in a train carriage across Canada during the freezing winter to Halifax, and then boards another ship to France. Two of his fellow laborers freeze to death next to him in Canada. In reality, around 50 laborers died in Canada on their way to Europe, according to RCI, a Canadian news publication.

Once they reach France, Zhang and other laborers work under the harsh supervision of British soldiers. They are forced into long hours burying dead bodies or repairing railways. They work through freezing rain, eat disgusting food, and are confined to camps surrounded by barbed wire fences. Their base is bombed and many die after contracting the Spanish flu.

Most of the details are accurate reflections of what historians know about the Chinese Labor Corps. They were mostly peasants, but also curious and idealistic intellectuals and students drawn to explore the developed countries of Europe, make money, and study. By the war’s end, thousands of Chinese had died due to disease or enemy attacks. The exact number of dead is disputed, with some putting it as high as 20,000.

Most laborers went back home after the war, but around 3,000 settled in France, establishing some of the country’s first Chinatowns. In Fan’s novel, Zhang stays in Paris, becomes a mechanic, and marries Marguerite. He plans to take his wife and child to visit his hometown in China before learning his family were killed in Jinan in 1928 (this is probably a reference to the Jinan Incident when the Japanese army killed over 6,000 civilians and soldiers).

Zhang feels like an orphan without a home. Faced with rampant racism in his adopted country, Zhang buries his laboring past and refuses to speak of it again, even keeping it from his closest friends and daughter Anne. Only in his final days, Zhang revisits the places where he had worked and sees old friends he had made during the war. He makes a stop at the cemetery in Noyelles-sur-Mer where, in real life, the largest Chinese labor camp was located.

If Wu’s mission is to produce a powerful reminder of the Chinese contribution to the Allied war effort, Souls Left Behind is an admirable attempt. Through parallel stories of Zhang’s life—one first-person account of his experience during the war and the other detailing his later life as a widower supported by his daughter, told from the third-person—Wu humanizes Chinese experiences of the war. For decades, these people’s contributions were largely unrecognized diplomatically and many records of their service were destroyed during the Second World War. In the UK, for example, concerted campaigns for greater recognition didn’t begin until 2014, according to The Guardian.

But reading Souls, it is hard not to relate Zhang’s struggles as an outsider to the modern-day scourge of racism. Wu, who was born in Nanchang, Jiangxi province, in 1974 and has lived in the US since she was 23, often features immigrant stories in her writing. Her previous novel, Beautiful as Yesterday, explores the mother-daughter relationship and sisterhood within a Chinese immigrant family in San Francisco. She has written about her passion for telling stories of ordinary Chinese people in her blog.

That the book was written at a time of heightened anti-Chinese sentiment in the US brought on in part by the Covid-19 pandemic is surely no coincidence. In Europe, too, hate crimes against Asians have become more common. In 2021, four French students were sentenced for racist anti-Chinese Twitter posts. Many more hate crimes go unreported as some countries refuse to collate race-based hate crime data, a Vice report shows. It’s an important reflection on historical racism at a time when anti-Chinese sentiment is prevalent once more.

Although Zhang’s experience with racism depicted in Souls is far from unique in immigrant stories, the lack of respect and racist treatment he receives is particularly evocative given he traveled thousands of miles from home to fight for what the Allies believed was a just cause.

Souls is Wu’s first novel narrated mostly through a man’s perspective. Wu has written about how she feels women’s voices tend to be marginalized in the male-dominated Chinese culture, so it’s no surprise that Zhang’s narrative features several strong female characters. Through Zhang’s relationships with his wife and daughter, Wu reflects the deep impact of war on both men and women. “How many women, I wondered, were being made widows by this war? How many, right at this moment, were losing their brothers and sons?” Zhang thinks as he packs ammunition to send to the frontlines.

Zhang’s wife, Marguerite, is the foundation for his new life in an unfamiliar country. She insists on working in an era when most women stayed at home and looked after their children. She teaches Zhang technical skills at the factory where they work, stands up for him in the face of racists, and protects her mother from her abusive father. Zhang’s daughter Anne also plays an important role as she struggles with her mixed-race identity. Earlier, when Zhang is injured by a bombing at Dunkirk, he is saved by a local woman whose husband is fighting at the front. Even Miss Lu, who features only briefly at the beginning of the book, is given a detailed story arc: She survives the war and political turmoil to live a decent life with her adopted children. The contrast with Zhang’s struggles in France is profound.

Zhang’s own emotions are sometimes eclipsed by other characters and the historical setting. He is a tool to showcase the laborers’ experience, their unfair treatment, and hard work, rather than a deeper individual.

One of the most interesting arcs in his story is his transformation from a wealthy, educated man to a lowly laborer, but Wu largely ignores this. It’s ironic that, in his attempt to escape feudal traditions he ends up caged within barbed wire fences after fleeing to France, and spends the rest of his life feeling guilty about abandoning his family and failing in his filial duty as the eldest son. But this is underexplored. His transition from comfortable gentry to manual laborer treated with disdain feels abrupt. Zhang assumes his new role relatively smoothly without much reflection and easily befriends fellow laborers from much poorer backgrounds.

Readers are made to wait for the emotional payoff from investing in Zhang’s story until the final chapter, and these passages aren’t always handled well. When Zhang’s first-born son passes away shortly after he learns his entire family in China has died, his coworkers add to his grief by calling him racist names and abusing him. But Wu describes these shocking events from the third-person perspective. Without Zhang speaking about them directly, Wu misses the opportunity to explain his internal struggles in a more direct and impactful way. In general, the first-person parts are more emotionally engaging.

Despite the flaws in Zhang’s character development, the book still effectively sheds light on the often-forgotten history of the Chinese Labor Corps in Europe. It’s a valuable, human perspective on China in the First World War and a reflection on the plight of Chinese immigrants to Europe in the 20th century. In today’s atmosphere of geopolitical rivalry, anti-Asian racism, and misunderstanding between China and the West, Wu’s book is more valuable still.