School psychologists struggle to protect students’ privacy and serve their mental health needs

When he first developed symptoms of depression in high school, Zhang Ning decided to go to see the on-campus psychologist. Expecting the visit to be confidential, he was shocked to discover afterward that his teachers and parents had found out about his condition.

“The school psychologist betrayed my trust, and everyone treated my traumatic stories as a joke,” Zhang tells TWOC years later, recalling he was so badly bullied by his classmates over his condition that he had to take a year off from school.

Now, Zhang is now one of many in China alarmed by a new policy, announced by the National Health Commission on September 11, that an assessment for depression will be added to the annual health examinations taken by high school and college students across the nation.

Though it was introduced in effort to address the Chinese education system’s long neglect of students’ mental well-being, the new policy has touched off widespread debate for its potential to infringe on students’ privacy, as well as whether China’s schools are currently capable of providing ethical and effective psychological services.

China is in the throes of a student mental health crisis. Shanghai’s Pudong district reported 14 student suicides in the first half of 2020, exceeding the annual average for the past three years. In June, state-run newspaper Health Times reported that 18 students had jumped to their deaths since March, one as young as 9 years old. The reasons for these suicides included intense academic pressure and harsh discipline by teachers and parents.

In 2004, a joint study by the Pediatric Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University and the Shanghai Academy of Education Sciences found that over 24 percent of elementary and middle school students in Shanghai had considered ending their life. Last year, 20 percent of 300,000 university students stated they were seriously depressed in a survey by the China Youth Daily newspaper on Weibo.

Public schools in China have employed psychologists and counselors since the 1980s. Since 2002, the Ministry of Education has required all elementary and middle schools to employ one at least one part-time or full-time “teacher of psychology” with a degree in education or psychology, and professional training certified by the government, who can provide counseling services and teach courses on mental health.

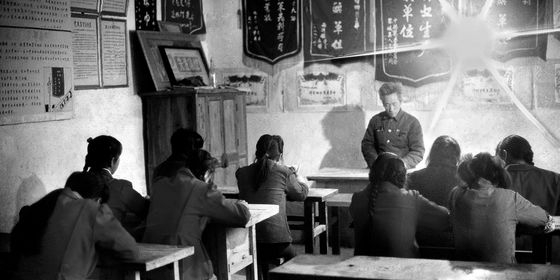

A high school psychological counseling office in Zhumadian, Henan province, which sees students nearly every day before the national college entrance exams

Existing mental health services at schools, though, often fail to meet students’ needs. Student privacy is a major stumbling block. Professional ethics require psychologists and psychological counselors to protect the privacy of their patients, informing a family member or responsible individual only if the patient is at immediate risk of harming themselves or others. Experiences like Zhang’s, though, are far from rare.

“I went to visit my school psychologist and told her I had depression. She asked me to fill out a questionnaire with a confidentiality statement confirming that our interview would be a secret,” wrote one user on Weibo. “The next day, I received a call from my mother, who said my college secretary had suggested I should go home to rest. Is that considered treatment?”

Counseling centers at universities and secondary schools are normally operated by the department of student affairs, which falls under school party committee responsible for ideological and political education. Beijing Normal University researchers noted in a 2009 paper that school psychologist and counselor positions are often filled by ideology and politics advisers, advisers of the campus Young Pioneers or Communist Youth League branch, or other faculty members.

Such individuals may prioritize the interest of the school over that of the students, or feel the need to report the student’s situation to their teachers in order to “correct” their behavior. Another paper, published in the journal Education in Management in 2002, noted it was not uncommon for school psychologists to keep students’ files in non-secure locations accessible to anyone, or provide them to school administrators when asked.

A lack of competent specialists is also to blame. Li Yuan, a programmer, tells TWOC that his high-school psychologist was also his Chinese teacher. “I don’t think she was very good [at counseling], since not many students went to her for help. The job took time away from her teaching, and she had to devote more of her energy to the position, like writing reports,” he recalls.

School counselors also have extra administrative burdens. “I have a lot of other work to do: teaching classes on mental health, writing papers and reports, recording day-to-day income and expenditure, and organizing students events on mental health,” complained a user on question-and-answer platform Zhihu who identified herself as an early-career high school psychologist. “I should be spending the time counseling students or receiving professional training.”

Many campus psychology centers continue to operate with “education” and “guidance” as their aims

Besides a conflict of interest, the conflation of psychological service with ideological education leads to poor quality of counseling on Chinese campuses. “I felt lectured, not counseled,” Jin Yang, an insurance worker who once consulted his high school counselor on his plan to drop out of school and become a professional esports player, tells TWOC. “[The psychologist] told me to study harder and think of my parents. Why didn’t she ask me the reason I wanted to be a esports player, or say anything about my hobby?”

School budgets usually only cover the cost of psychological services for mild conditions. Students with severe conditions, such as those who need medical attention and medication prescribed by a psychiatrist, usually have to go to the hospital.

Yet these services are not always covered under the national health insurance scheme, leaving them out of the financial reach of many students and their families. “A novice psychologist can cost at least 300 yuan per hour. Those who are experienced can cost thousands of yuan [per hour],” a master’s student in psychology in Beijing, surnamed He, tells TWOC. “In many cases, clients need treatment more than once. Some need treatment for years.”

A high school in Zhejiang province organizes a stress-relief activity for students before exams

Lingering stigma surrounding mental illness also prevents many students from seeking help. At the start of his first semester of college, Lin Huan, a student who suffers from depression, had to take an online questionnaire about mental health under his real name and student ID number. He tells TWOC he avoided answering some sensitive questions, like whether he felt lonely or wanted to hurt himself , “just in order to be normal.”

“Who wants others to know they are ill?” asks Lin, who says students who gave affirmative answers to those questions were asked by their class adviser to see the school psychologist on a week basis. “I do not want to experience discrimination, even though I am depressed. I can pretend to be happy.”

I recently visited a psychologist at my university for anxiety problems. Prior to my visit, I had to book the appointment online and provide detailed personal information, such as my name, class number, phone number, and the name and phone number of my class adviser. I even had to upload a photo of my ID card, which made me nearly give up trying to visit.

During the 50-minute pre-appointment examination, the psychologist asked me several questions, like “Did you experience something that had a significant impact on your life?” and “Have you ever intended to hurt yourself or others?” She worked part-time as a psychologist at my university every Tuesday and Friday.

I cannot judge the quality of the session, though I did feel comforted after our talk. However, when I left the counseling center, which was located in the corner on the second floor of an administrative building, I heard two other students gossiping. “Is that an office? Who would put an office in such a hidden location?” one of them asked.

“It’s the psychological counseling center. It’s just for mental illnesses,” the other replied. I saw them giving me strange looks, and this made me feel upset and alienated.

“I really don’t understand. If someone is diagnosed with depression, all their teachers and classmates will know, and then there will be no way for them to stay [at the school],” Zhang says of the National Health Commission’s new policy to test for depression.

Under the new guidelines, secondary schools and universities will need to create a file on mental health for each student, and “pay close attention” to students who achieve “abnormal” results in the psychological assessment, without specifying what form this will take. Schools will be required to have a counseling office and mandatory courses on psychology for students, and teach students to recognize the symptoms of depression and seek help. The policy also calls for online psychological testing and mental health education to be available to the wider public.

But many remain skeptical until schools can improve their psychological services, or until society’s attitude toward mental illness change. “The new guideline must help students deal with mental health issues with the existing medical resources at school,” education expert Xiong Binqi told Beijing News, emphasizing the need for schools to improve their protection of students’ privacy. “Otherwise, this will create even more psychological pressure and harm on students whose test results are ‘abnormal.’”

Additional reporting by Hatty Liu and Tina Xu

Names have been changed in the story

All photos from VCG