By blending tradition with modern pop culture, northeastern “errenzhuan” was catapulted into the big leagues of Chinese showbusiness—but at what cost?

It is ten minutes before curtain-up, and the Master of Ceremonies of the Dongbeifeng Errenzhuan Theater in Changchun, the capital of Northeast China’s Jilin province, is very happy to see a foreign face in the audience. “England! Football! Oh yeah!” he shouts in English to TWOC with a laugh while enjoying a cigarette with friends.

Behind him his theater is lit up like a Broadway stage. Lamps illuminate full-length posters with enticing action shots of the night’s performers, while a suona, a shrill double-reed horn, squeals to a recording of a thumping electro beat from hidden speakers. “I was at the Jilin Academy of Arts. Actually, how about you write Communication University in Beijing? That sounds better,” the MC asks.

Tonight, it’s all about buying low and selling high—how else to get the bodies in the seats? As audiences in Dongbeifeng’s house laugh along to jokes on stage about female body image or other current social kickers and applaud with plastic “clappers”—hand-shaped noisemakers the theater provides specifically for that purpose—it’s easy to believe that errenzhuan (二人转), a folk performance combining vaudeville and Chinese opera, has escaped the decline that most traditional opera and performing arts seem fated to go through in modern China.

Yet there’s a price to this strategy of reviving a traditional art by catering solely to audience tastes. As the northeast’s most popular cultural export, errenzhuan is viewed fondly, as indispensable a part of Dongbei culture as freezing temperatures and over-drinking. To others it’s a vulgar relic of a more backward time, when audiences were only entertained as they were unsophisticated and didn’t know any better. Competition amongst actors is fierce, while their performances must balance between the coarseness that first made the genre popular, and not re-sparking the offence that caused it to fall from grace.

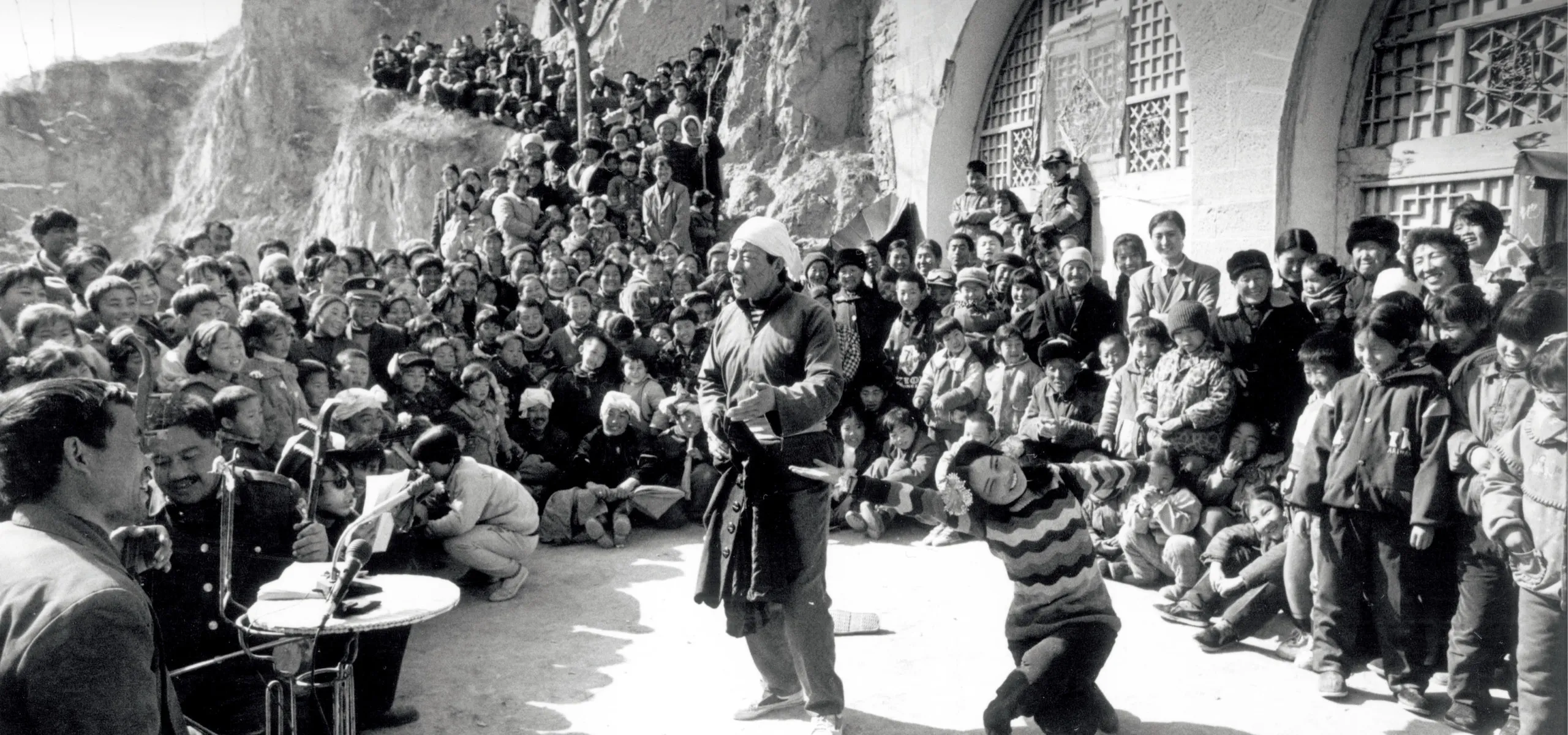

Errenzhuan, literally “two-person rotation,” allegedly originated in the sketches performed on urban streets, or given as private performances for northeastern families while sitting around the kang (heated brick bed) after a day’s work. In a typical performance, a man and a woman would sing scenes from literature or folk tales, with dance and coarse banter. Performers would play multiple characters, and they were usually not professionals—instead, they were ordinary peasants making ends meet when there was no work in the fields.

The off-duty farmers of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), though, would be hard pressed to recognize the errenzhuan on Dongbeifeng’s stage. On this Friday night, the audience of around 150 people is treated to a hodgepodge of a buzzcut hip-hop dancer screaming into the mike while smoke and lasers flash everywhere; acrobats who once appeared on the Henan TV Spring Festival Gala, twirling their bodies through hanging crimson fabric high above the auditorium; a sketch comedian impersonating Osama Bin Laden (with a large fake beard, and throwing a shoe in lieu of a grenade); and a strongman chugging whole bottles of beer by picking them up off the floor with his mouth, all with a metal bar wrapped tight around his neck.

This is what you get after 30 years of playing to the market, competing with modern entertainment to attract viewers. “In an errenzhuan performance, everything is to make the audience happy,” Ma Pu’an, Chairman of the Jilin Dongbeifeng Culture Communication Company, told the Bohai Morning Post in 2009.

Like other folk arts, errenzhuan companies were given the elite treatment after the founding of the PRC. They were able to perform in urban theaters and recruit talents elevated to the artistic establishment. But with the market reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, independent errenzhuan theaters innovated to make money. They brought the genre to karaoke bars and night-clubs, turning it into something closer to stand-up or sketch comedy.

This was when “errenzhuan began to evolve,” Dr. Haili Ma, associate professor of performance and creative economy at Leeds University, tells TWOC. Errenzhuan performers were adapting to compete with the encroachment of TV, pop songs, and western dance, into the entertainment market in the 1990s. Thanks to giving the audience what they want, errenzhuan saw a popular boom. If you can’t beat them, join them.

The industry’s best success story is Dongbeifeng’s rival theater chain Liu Laogen, which currently operates nine theaters across the country and boasted an annual turnover of around 148 million yuan as of 2014 according to the research of Dr. Ma. The most recent registered capital (a good indicator of a business’s size and scope) of its parent company, the Liaoning Folk Art Troupe, was 125 million yuan according to company information database Qichacha.

Errenzhuan performers became superstars—none more so than Zhao Benshan, an errenzhuan performer from peasant origins in Liaoning province. Ever since his debut in the 1990 CCTV Spring Festival Gala, Zhao has not only become a national treasure and the face of errenzhuan, but began starring in major Chinese films like 2007’s Going Home. By 2009, he was able to charge 300,000 RMB for each stage appearance according to The Founder, a Chinese magazine.

It was errenzhuan’s newfound popularity at the grassroots, Dr. Ma argues, that led the central government to support errenzhuan as a new elite art form. “There was a growing awareness of using native culture to build a national identity,” she writes in a paper from 2019, “and errenzhuan, by then a traditional folk form turned regional popular culture for the working class and peasants, was recognized as being an ideal subject to reinforce the CPC founding ideology and legitimacy.”

Fame, though, led to market saturation. Peasant children flocked to errenzhuan schools, leading to a boom in education: In Jilin city alone by 2005, there were over 30 such schools, recruiting up to 500 students annually. Students hoped to earn their fortune like Zhao, causing an over-supply of performers and lowering performance quality. “Increasing numbers of actors were competing for limited performing opportunities,” Ma writes, “leading to a standardization of the art form where actors were only differentiated by the increasing amounts of sexual connotation they were prepared to insert into their performance.”

Dirty jokes were always a crucial ingredient to errenzhuan’s grassroots appeal, much as conservative officials were loath to admit it, but they became more frequent in this period, even at the top of the ladder. Audiences roared with laughter in the 2009 CCTV Spring Festival Gala when Zhao Benshan called his male comedy partner an “ass kisser” (slang for homosexual) for wearing a skirt. The rise of the internet aided the transmission of errenzhuan’s rude jokes, “sketches with the most explicit sexual dialogue…became the most downloaded and viewed,” writes Dr. Ma.

Yet official opinion could be capricious. Despite netizen support for Zhao and his brand of humor, in 2010, Han Zaifen, vice-chair of the Chinese Theater Association, called errenzhuan “grotesque, with not a trace of cultural value and depth.”

But how to reform errenzhuan when the grotesque had always been key to its success—was, indeed, integral to its identity? Despite Zhao having campaigned since 2003 for “green errenzhuan” suitable for family viewing and advocating cleaner performances in his theaters, he believed a complete reform would damage the medium. “Errenzhuan is like pig’s tripe,” Xinhua reported him as saying in 2014 in response to criticism. “Once it is thoroughly cleansed, it is no longer errenzhuan.”

President Xi Jinping decided the matter in 2014, declaring at the annual meeting of art critics and creators known as the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art (which Zhao was notably absent from, unlike in previous years) that art forms which “blindly chase and cater to public tastes and vulgar interests” needed to remember that their primary purpose was to serve “the masses and the Party.”

Since then, “there has since been very little media exposure of errenzhuan,” writes Ma in her paper, noting on a visit to Liu Laogen in 2015 no coarse jokes or sexual references in the entire show. Instead, there were frequent video clips between performances narrating the transformation of errenzhuan to “‘green errenzhuan’…fit for all ages.”

The earthier jokes are still there at Dongbeifeng, but scaled down to coy levels. “Oh that’s what you care about?” the MC chuckles knowingly when asked about off-color content in the performance. “We’ll definitely have that here!”

But there’s nothing of Zhao’s ass-kisser caliber. “If I slip, then all is lost!” announces an acrobat stretched in a split between two cinder blocks, gesturing at his crotch. “Applaud for me, and you will get money!” one dancer yells, a pile of 100 RMB bills appearing on the giant LED screen behind him. “And beauties!”—the screen switching to women in skimpy bikinis.

Some performers still seek stardom, especially at Liu Laogen, the acme of the errenzhuan scene. An acting career is still possible, thanks to Zhao owning a TV company that produces comedies for online platforms and casts Liu Laogen performers.

At Dongbeifeng, a big theater by industry standards, “the elimination rate is still pretty high,” Dongbeifeng director Li Yunjie told Portrait magazine in 2018. Actors do not have a long-term contract, indeed are only paid for 10 days’ work in advance, meaning they are continuously in danger of losing their job to someone better. Such a hand-to-mouth existence means few errenzhuan actors go on in the business past the age of 40, and it’s rare to see a woman over 35.

In the performance itself, the competitive nature of the industry manifests in demands for applause—sometimes a little too often. Three minutes were taken up by one comedy duo forcing the audience to clap along as they danced onstage. “Sorry to keep asking you to applause,” says the beer-drinking giant. “To you, they’re just plastic hand-clappers. To us, it is everything.”

But there can be no doubt that errenzhuan performers have had their wings clipped somewhat—limited in what they can do onstage, and how far they can rise off it. “Before, errenzhuan actors used to compete with acting talent,” says a pint-sized stand-up during his slot. “Now they do so by how much they can drink and how much applause they can get.”

Make ’Em Laugh: How a Northeast Folk Performance Escaped Decline is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.