Halloween may be a Western import, but ancient Chinese literature is full of spooky beasts, demons, and ghosts to consider this October 31

With Halloween just around the corner, you may be dusting off your zombie costume, or cutting eye-holes in a bed sheet to turn yourself into a ghost. But there is another way: How about dressing up as a traditional Chinese supernatural being?

Despite Halloween (万圣节 Wànshèngjié, literally, “10,000 Saint’s Day”) being a Western import, there is no shortage of monsters and demons in traditional Chinese literature. But rather than wade through the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) fantasy epic Journey to the West or Pu Songling’s renowned collection of ghost stories from the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, to learn about these infamous devils, TWOC has prepared a guide to some of the most renowned monsters for you to consider as your Halloween costume.

First, though, let’s clear up some terms. Like in English, Chinese has many words representing different kinds of scary creatures. For example, 妖 (yāo) are evil spirits that are transformed from magic plants or animals; while 怪 (guài), or “monster,” are beasts, or even non-living objects such as jade and musical instruments, with grotesque appearances. 魔 (mó), on the other hand, refers to devils or demons that seek to harm or kill humans. Sometimes, celestial beings also fall into the 魔 category.

Meanwhile, the character 鬼 (guǐ) means “ghost.” It’s said if a person dies in an unjust way, their spirit will become a “hungry ghost” that haunts the world seeking sustenance. 鬼 is also a radical found in other characters which refer to various monsters, demons, beasts, ghosts, and other supernatural (and usually unpleasant) creatures.

A difficult-to-write chengyu, 魑魅魍魉 (chīmèi wǎngliǎng), contains the names of three types of ghost to beware. This idiom, originally a shorthand for ghosts and monsters of all kinds, is now a metaphor for evil people in society.

The first monster mentioned in the idiom is the 魑 (chī), which was also written as 螭 in some ancient texts. This frightening beast is believed to be a mountain deity with a monstrous appearance, that hides in the woods waiting for defenseless people to prey on.

Ancient scholars had different opinions on the chi’s appearance. Wen Ying (文颖), a scholar living in the late Eastern Han (25 – 220) dynasty and early Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280), wrote in his Notes on the Book of Han (《汉书注》) that the chi was “the son of a dragon.” Zhang Yi (张揖), author of Guangya (《广雅》), a dictionary published in the third century, stated that the chi was a female dragon without horns. Also in the Eastern Han dynasty, Xu Shen (许慎), author of Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》), the first comprehensive dictionary of Chinese characters, described the chi as “like a dragon, with a yellow color.” Putting all these descriptions together, the chi was generally depicted throughout history as a dragon-like creature living in the mountains, often attacking passersby.

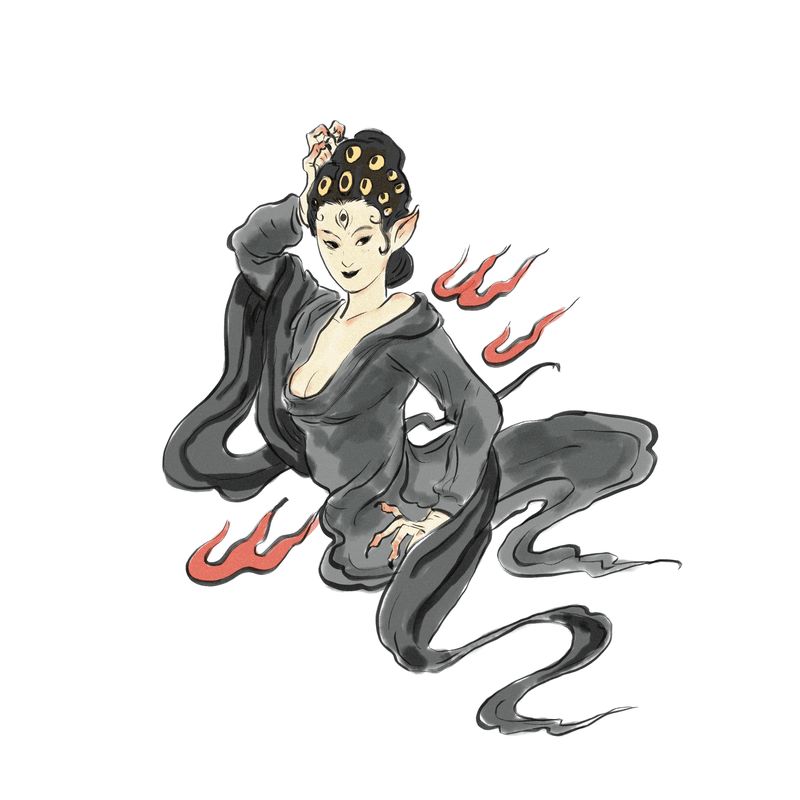

Or, why not go to your Halloween party as the second creature mentioned in the chengyu: 魅 (mèi)? In his dictionary, Xu wrote: “Mei is the spirit of old objects.” The mysterious mei is like the siren, who has an attractive appearance and can enchant people to fall in love with it and then do its bidding. Mei can come in many different varieties, but the most widely-known and feared is the 木魅 (mùmèi), or “tree mei,” which transforms from an old tree or an animal living in the tree. The Tang dynasty (618 – 907) poet Li He (李贺), once described a mei in a poem: “The 100-year-old owl turns into a tree spirit, who burns its own nest and laughs in the flames.” Since mei are said to be intoxicatingly beautiful, folk tales often depict them in the form of attractive women.

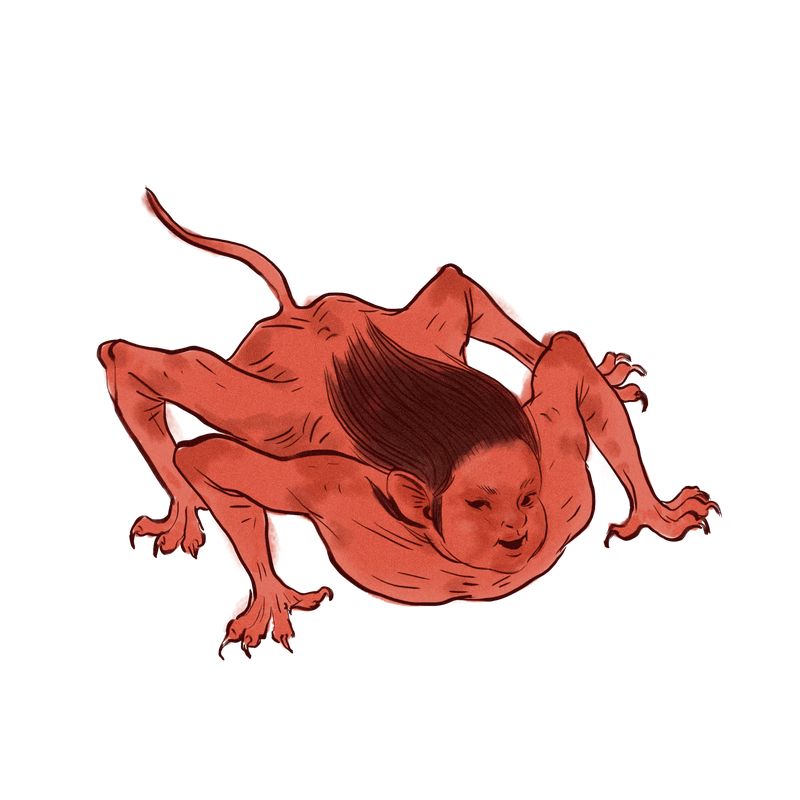

The final part of the idiom mentions the 魍魉 (wǎngliǎng), a ghost that causes epidemics. According to In Search of the Supernatural (《搜神记》), a collection of ghost stories from the Jin dynasty (256 – 420), the wangliang was originally a son of the mythical ruler Zhuanxu (颛顼), one of the legendary five emperors of Chinese mythology. It recorded that “Zhuanxu had three sons, but they all became ghosts after death. All of them spread diseases in the human world. One lives in the Yangtze River, and was named the Nue Ghost (疟鬼, ‘Malaria Ghost’); one lives in the Ruoshui River, and was called the Wangliang Ghost; and the other one lives in people’s homes and likes to scare children, and is known as the Child Ghost (小鬼).”

In Huainanzi (《淮南子》), a philosophical work from the Western Han dynasty (206 CE – 25 CE) written by nobleman Liu An (刘安) and some of his retainers, the wangliang “looks like a 3-year-old child with dark red skin, red eyes, red claws, long ears, and beautiful hair”—a useful description for those looking to dress up as the wangliang on October 31.

Another monster originally of prestigious birth is the 魃 (bá). According to The Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》), a compilation of mythic geography and beasts believed to have been completed before the Han dynasty, the Yellow Emperor, who is supposed to have been the first ruler to unite warring tribes into what eventually became today’s China, had a daughter called 女魃 (Nǚbá). She was the goddess of drought, and always dressed in black.

In a fierce war, the Yellow Emperor fought Chiyou, the leader of a rival tribe, who summoned the God of Wind and God of Rain to aid his attacks with howling storms. The Yellow Emperor retaliated by ordering Nüba to ward off the storms with her drought-inducing powers. With Nüba’s help, the Yellow Emperor eventually won his war with Chiyou, but his daughter had spent so much energy in battle that she no longer had the strength to return home to the heavenly mountains. Therefore, Nüba was left in the human world.

But she wasn’t welcome here, since wherever she went, she brought severe drought with her. Gradually, after receiving countless rejections and endless hostility from humans, Nüba became an evil monster spreading drought deliberately, known as “旱魃 (Hànbá).” It’s said that Hanba lives in the north of China, hence why it’s so much drier there than in the south.

The final monster you might consider dressing-up as for Halloween is the 魈 (xiāo). This is a mountain-dwelling creature with one foot. It’s also known as “山魈 (mountain xiao)” and the “Gan giant (赣巨人).” The earliest description of the xiao comes from The Classic of Mountains and Seas, which says: “There is Gan giant in the South. It has a human face and long arms. Its body is black and hairy, and the heel of its foot points forward. If you smile at it, it will smile too.” In Baopuzi (《抱朴子》), a Daoist classic finished in the Eastern Jin (317 – 420) dynasty, author Ge Hong (葛洪) gave a more detailed description of the monster: “The mountain spirit looks like a young child and has a single foot with the toes pointing backward. It likes assaulting people at night.”

But if you’re out on Halloween and happen to come across a fearsome xiao, don’t panic—according to Ge, simply shouting “xiao” can place a spell on the monster so that it won’t attack you. Whether mei, xiao, chi, or Nüba, at least consider ditching the toilet-roll mummy look, and scare your friends the traditional Chinese way.