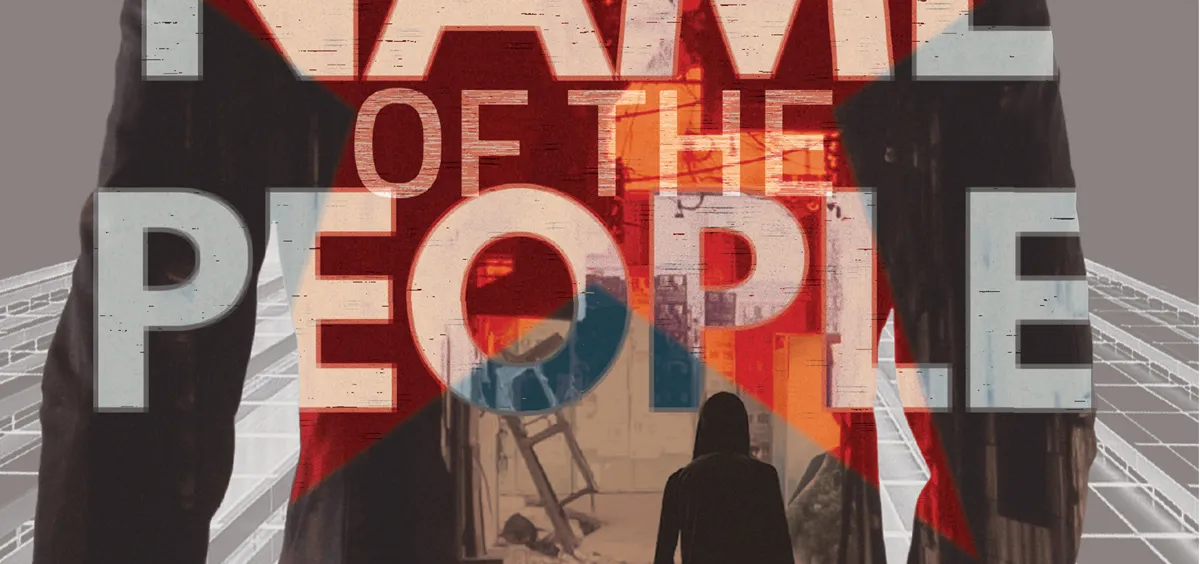

Zhou Meisen’s popular novel tackles corruption and scandal at the heart of Chinese politics

“We can’t raise these sorts of lazy pigs who only trample on the food of the masses,” rails the party secretary of the fictional H province in In the Name of the People, Zhou Meisen’s scandalous novel that takes on sloth and corruption within the government.

In comparing H province’s party committees and government bureaus to pig farms, Zhou, a former municipal deputy party secretary and businessman, invites readers to join him in lambasting the grubby practices and rotten morals of officials in his dramatic novel. The twisting narrative, which follows an anti-corruption chief’s attempts to eliminate graft in the province, explores the motives for corruption in political and business circles where almost no one is totally clean.

In the Name unfolds much like a murder-mystery thriller, except the central crime is not an act of violence but the escape of a crooked official. What first seems like a straightforward case of Ding Yizhen, the vice mayor of Jingzhou city who is accused of accepting bribes, eventually emerges, over the course of 500 pages and 54 chapters, as a complex web of corruption that goes to the core of H province’s political brass.

Originally released as a web novel in 2017 at the height of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, and adapted into a hit TV series of the same name, In the Name is inspired by many of the real incidents that peppered Chinese news around that time. At least one moment in the book, when a low-level cadre in Beijing is found with a secret mansion stuffed with cash, is based on a real-life case: that of Wei Pengyuan, an energy official found with a cache of over 200 million RMB at home.

But other parts are familiar without being directly lifted from the news columns of Xinhua: officials caught in bed with prostitutes; workers who refuse to leave a factory that has been slated for demolition; thugs sent to carry out the dirty work of the police; grubby deals conducted over shots of baijiu; and rampant gift giving.

Zhou weaves the debauched lifestyles of the myriad characters in high office and business into an impressively rich nexus of connections and relationships. Some characters are satisfyingly ambiguous, while others are forgettable stereotypes. One of the least interesting is the hero, Hou “Monkey” Liangping, the director of H province’s Anti-Corruption Bureau.

Hou is pure caricature: morally unimpeachable, handsome, buff, intelligent, and, thus, extremely dull. When Hou is not busy exhorting the ideals of public service (“When we put these uniforms on, we swore an oath of loyalty to the country, loyalty to the people and loyalty to the constitution and the law!”), he is refusing gifts, pointedly turning down baijiu for mineral water, and indulging in his favorite hobby: the parallel bars (hence the sculpted body). Hou is the James Bond of Zhou’s work—only with a less interesting sex life, worse one-liners, and no humanizing flaws.

Mercifully, there is a plethora of more interesting characters, each with their own faults and internal conflicts. High-ranking officials spend plenty of time spouting party platitudes in formal meetings, but eventually all come under suspicion as their private lives emerge as tangled messes. The initially measured and stoic Gao Yuliang, deputy secretary of the provincial party committee, slowly gets dragged down into a pit of accusations and reveals a ruthless streak. Meanwhile, the shady Li Dakang, a hothead with a checkered past as a trailblazing and Machiavellian economic reformer, emerges as a competent but hated figure.

Failed marriages, affairs, and factional infighting give color to these representations of the ordinarily bland leaders on Chinese television—Zhou’s novel is an enticing suggestion of what messy private lives might lie behind the façade.

Zhou also acknowledges that corruption isn’t clean-cut. The tensions between GDP growth, environmental protection, personal enrichment, and “greasing the wheels” of development are made clear. “Combating corruption and building a clean government isn’t the only work that needs to be done in Jingzhou…Eight million and eighty-three thousand people need to survive, need development, need jobs, need to eat and need peace,” argues Li Dakang, the reformer. These contradictions in Zhou’s novel are the reality in a China that has seen breakneck growth over the last 40 years, but also expanded opportunities for officials to enrich themselves at the public’s expense.

This intriguing underlying theme does much to carry the novel, as the writing itself suffers throughout from needless exposition. Zhou feels it necessary to frequently tell the reader that characters are “feeling uneasy,” or “just know something doesn’t feel right,” which is probably meant to build tension, but loses its efficacy after the fifth or sixth time, becoming superfluous and annoying.

Women are also needlessly stereotyped. Though conspicuously absent from political circles (as they are in real life), there are some important female business leaders in Zhou’s corrupt world. Most, however, enter the narrative by virtue of their good looks, where they are used to seduce and offered as bribes to the men in the story. One particularly cringe-inducing passage comes when a businesswoman on the run gives herself away because of her uncontrollable urge to shop: “Her womanly nature started acting up, and she had wanted to buy some nice clothes…women will be women!” goes her internal monologue.

Despite these flaws, Zhou’s narrative builds in intrigue as we follow the chain of money and connections to the top. Though the narrative focuses on what President Xi has labelled “tigers,” powerful high-ranking officials guilty of breaching Party discipline and graft, it also looks at the dealings of low-ranking “flies.”

Though neither comes off well in Zhou’s portrayal, there is some sympathy for those lower down the chain of command: “Without the attention of senior officials, it was easier to get to heaven than it was for grassroots level workers to get something done. This is the current state of China,” laments one old cadre. Some of the most interesting moments from the novel stem from acts of negligence by relative small potatoes, as well as when Zhou takes a break from progressing the plot to allow characters to develop.

The cultural impact of In the Name as a work that directly confronts government corruption has been well documented, especially when the 2017 TV adaptation was released. Then, it was hailed as “reflecting China carrying out the struggle against corruption, and answers the people’s desire to eliminate corruption” by the People’s Daily newspaper.

The author’s desire to clean up government is certainly clear. In the afterword, Zhou complains that “people nowadays can so deplorably swindle and rob each other in order to make a quick buck,” and seems to view his writing as a public service: “Art must serve society.” The solution for H province’s corruption, suggests the novel, is to put more upright, incorruptible, and morally unflinching characters in government, like the hero, Hou.

In the final act of In the Name, Hou is as committed as ever to bringing the corrupt to justice. But after the endless backstabbing, backroom deals, nepotism, personal enrichment, and scandals at all levels throughout Zhou’s drama, one is left wondering just how many officials in H province are actually totally clean, and whether there would be anyone left to govern if every minor infringement were to be investigated.

As Hou himself comments, “Officials become corrupt officials. Businessmen become profiteers. Commoners fight and scramble for the petty advantages they have in their sights; who’s to say they won’t become corrupt officials the moment they get their hands on power?”

Shadow of the Hunter

This novel by Su Tong centers on the love triangle between three teenagers in a small southern Chinese town in the 1980s. A violent sexual assault, followed by a false accusation, changes their lives forever. Ten years later, and still shadowed by the past, the three protagonists reunite for a final clash. The novel’s Chinese title, Chronicle of the Yellow Finch, is a reference to the Chinese idiom, “The praying mantis stalks the cicada, unaware of the yellow finch behind it.”

Tiny Moons

This delightful essay collection on food and identity by poet and writer Nina Mingya Powles records a year that the author spent in Shanghai studying Chinese, exploring the urban landscape, trying out foods, and finding out the connection between her childhood and who she is today. Born in New Zealand, Powles has lived in Wellington, Kota Kinabalu, and Shanghai, and has always been inspired by food that ties her to her Malaysian-Chinese heritage. From pan-fried dumplings to pisang goreng to spring onion oil noodles, each dish inspires anecdotes and warm personal memories, which are aptly illustrated by Emma Dai’an.

Two Lives

Crime is a major theme in the oeuvre of A Yi, a leading author from the 1970s generation who worked as a police officer before embarking on a literary career. His works have been translated into seven languages across the world. In this collection of five short stories, repressed individuals and twisted romance lead to horrible crimes of passion. A Yi’s masterful depiction of mental instability renders everyday life surreal, unpacking as events with layers and often shocking final realizations. – Liu Jue (刘珏)

The People’s Price is a story from our issue, “High Steaks.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.