Two young Tibetans recall how the festivities of Losar, the traditional New Year on the Plateau, have changed and stayed the same since their childhood

On New Year’s Eve according to the Tibetan calendar, which falls on February 20 this year, 27-year-old Hualjor Tsering comes together with his family in western China’s Qinghai province to share a pot of Tibetan guthuk.

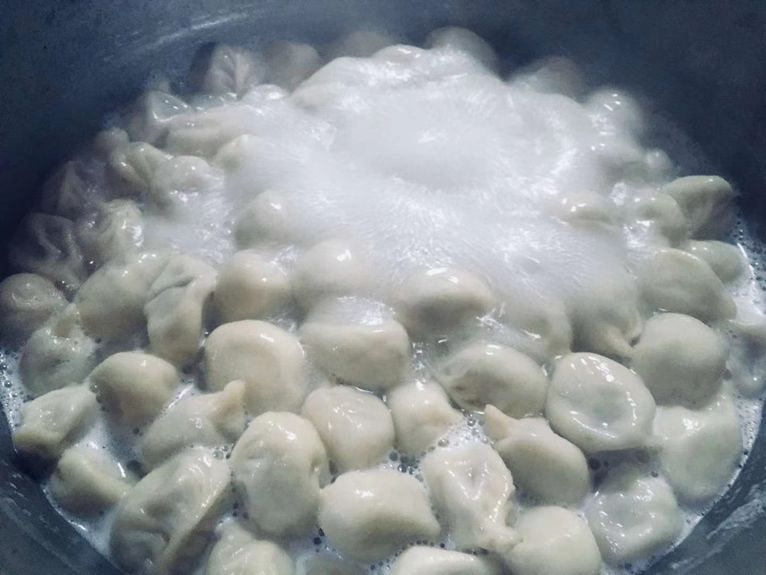

As gu means nine in Tibetan, the stew is made of nine ingredients including yak meat, highland barley, beans, radish, milk dregs, raisins, and dough balls. “Young people like to put the dough balls into hot pot,” says Hualjor, who now works in Sichuan province, home to more than 1.4 million Tibetans due to its close proximity to the Tibetan Plateau.

Tibetan New Year, or Losar, marks the beginning of the Tibetan lunisolar calendar, which is based on the Indian Kalachakra calendar first translated into Tibetan in 1027. Celebrated in China as well as Nepal, Bhutan, and India, Losar sometimes takes place at the same time as the “Spring Festival” observed in the rest of China, but can also take place up to a month later, as the Tibetan calendar operates on a 12-month system with a 13th “leap month” added every few years.

Over 1.5 million Tibetans live in Qinghai, which counts for 25 percent of the total Qinghai population. Almost half of Qinghai’s population lives in the capital city, Xining, while the region is famous for its vast stretches of sparsely populated areas such as the Tsaidam Basin.

Hualjor’s family hails from Jainca county, a rural area southeast of Xining where over 60 percent of the population is Tibetan, meaning many Losar traditions can still be observed starting from the last month of the Tibetan calendar. To prepare for the festivities, the family hangs lucky charms around the house such as colorful eyes of dyed barley, khapse (a dough snack fried in yak butter), and chemar (a beautifully decorated wooden box filled with wheat and tsampa barley). People can take a bit of wheat and tsampa from the box, throw it into the air to worship the gods, and say “tashi delek,” meaning "best of luck" in Tibetan.

On New Year’s Eve, the family packs “surprises” inside the guthuk—wool, small pebbles, or peppers—that are said to reveal something about a person’s character. Whoever gets a dough ball with wool inside is believed to be softhearted, for example, whereas getting a pebble implies strong-mindedness. “When I spat out peppers, my family burst out laughing,” Hualjor recalls from Losar celebrations last year—he’s soft-spoken, but peppers symbolize someone who is sharp with their words.

The leftover guthuk is thrown into a jar for “hungry ghosts” at the end of the night. The family then takes tsampa barley and rubs it over their bodies as if it were soap to “wipe off” bad luck. They then throw everything out, hoping to take all the bad luck away.

When Hualjor wakes up the next morning, he likes to start the new year by drinking yak butter tea and scoops a bowl of rice with droma, also known as “ginseng fruit,” a herb that grows 3,700 meters above sea level. He sprinkles some white sugar on top and pours some hot yak butter, which melts into the rice.

After this, the first order of the day is weisang, a ceremony to burn pine and cypress branches for the mountain gods. Weisang is an ancient tradition that supposedly dates back 3,500 years—in the Tibetan oral history Epic of King Gesar (《格萨尔王传》), dated between 300 BCE and 600 CE, Tibetan troops are shown to perform weisang to ask for blessings, and today, temples and villages in Tibetan areas often have ovens dedicated to the ceremony.

Hualjor also enjoys hiking up the mountains to hang prayer flags in the order of blue, white, red, green, and yellow, representing the sky, clouds, fire, water, and earth. Every time the wind blows the flags, the prayers are said to travel to the ears of the gods. Unlike weisang, which can be performed daily, prayer-flag placement ceremonies are typically conducted only once a year during Losar. “I usually go with around 20 cousins,” says Hualjor.

The solemn religious ceremony gives the cousins the opportunity to gossip and toast with barley wine on the mountain after a long year apart. While Losar, like the Spring Festival, traditionally lasted 15 days, it’s rare these days for young people working in the cities to be able to spend the full period at home. In the Tibet Autonomous Region and Tibetan prefectures in other provinces, the local government typically guarantees a holiday of three to seven days, but those like Hualjor, who reside in other provinces, must ask for time off. “I wish we could have more public holidays for Losar,” he says.

Dorjee Thinley, a 38-year-old thangka embroidery artist who typically resides on the Sichuan side of Lugu Lake, went back to his hometown in the province’s Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture over a week before the New Year. Though there is a public holiday in Garzê itself, those who work or go to university in Chengdu have already gone back to the city.

There is cheerful mumbling in the background, sounding like people greeting one another, as Dorjee speaks to TWOC over voice message on New Year’s Eve. He says the festival feels different now compared to his childhood. “When we were kids we were poor…so during Losar there would be lots of new clothes and stuff you’d never eaten before, and you couldn’t wait for the day to begin,” he says. “Now you feel indifferent; there’s money to eat whatever you want and go wherever you want.”

But despite the absence of some family members, and the distraction of mobile phones at the guthuk table, most of the traditions remain unchanged for those who do make it back home for Losar. “Faith is important in these parts,” Dorjee says. “We’ll burn incense at the temple in the morning…if you go to the river, you’ll see lots of people burning tsampa like [Han people] burn paper offerings.” On one’s way back from the temple, he says, it’s customary to sprinkle tsampa in other people’s homes, and people throw tsampa at each other on the streets—almost like a snowball fight—for good luck.

Perhaps these ”battles” are possible because, as Dorjee claims, a person can’t curse or fight with other people on New Year’s Day, or they’ll spend the entire year getting angry or fighting. “People really don’t get angry in our parts. I could go up to a stranger now and throw tsampa at their head, and they won’t object,” he says. “Just tell them ‘Good luck and happiness to you,’ tashi delek—whether you know them or not, whether they are Han or some other ethnicity, just throw some tsampa on whoever you meet.”

Additional reporting by Siyi Chu (褚司怡) and Hatty Liu