The fantasy of owning an independent bookstore lingers for China’s idealists

In the small tourist town of Yangshuo, Guangxi, a crowd meandered into a cement structure more akin to a tool shed than a house. They were dressed comfortably: some with necklaces and bracelets, some with tattoos, but all came with a book. This was the opening party for the southern town’s first independent bookstore, One Book Shop.

Inside there was enough room, appropriately, for one bookshelf, a counter with a coffee maker, a minifridge, and a table in the middle of the shop. This was covered with an array of cakes and treats provided by the owner, Jeff Peng. The books brought by the attendees were donations; they were placed on the bookshelf for future guests to enjoy.

The bookshelf needed some filling out, and Peng’s merchandising scheme would not do the job alone. As he explained: “I sell one type of tea, one type of coffee, and one type of book. It’s simple.” In this way, the bookstore is fundamentally idealistic. It was a realization of Peng’s dream, and as the opening party wore on, he waxed poetic about this vision: “Yangshuo is a cultural desert,” Peng said. “My bookstore will serve as an oasis.” The crowd protested back: “What are you saying? We’re full of culture!”

Even in the age of online book sales, bookstores remain an important aspect of China’s literary culture. However, they are taking on a new look. In response to an inability to compete with online sales, the idea of creating a space attractive to readers is increasingly important. Coffee shops are becoming synonymous with bookstores; various events, from book clubs to guest lectures, are becoming as vital as the books themselves. Chain bookstores are also beginning to provide these services, but while behemoths like Page One or Yanjiyou may win for their size, they remain mere imitations of the core of this movement: the independent bookstore.

Opening a bookstore in China is not an easy task, especially given the popularity of online retail and rising rent prices. China’s popular community-based question-and-answer website, Zhihu, contains a thread bearing the question, “How to open your own independent bookstore?” This thread’s top-rated post provides a variety of tips on everything from how to bolster the store’s reputation—to wit, by inviting authors, holding events, and buying a projector—to minute details such as an appropriate size for such an operation (50 to 60 square meters, apparently).

While the top post acknowledges the difficulty of the undertaking, it is optimistic compared to others. Another user named Cai Huixian is far more bluntly pessimistic: “Don’t open an independent bookstore; it is not as easy as you may think or feel. It requires too much knowledge, too much effort, and too much money.” On the other hand, Wang Tong, the manager of Yijia Bookstore, an independent bookstore in the southwestern provincial capital of Kunming, has a more moderate view: “I don’t think that any trade is easy, especially if you want to do it well.”

Yijia Bookstore was originally founded by two workers who took a liking to the independent bookstore culture in China. So, after acquiring a 100-square-meter space on the ground level of an apartment complex near the city’s largest university, they opened up a shop. Eventually, Wang, then a barista, was brought on board as manager. Over a year later, he’s still there.

An independent bookstore “is kind of like your home,” Wang explained. “The people who live in it determine what kind of environment it will have.” And for Yijia, those include students and professionals looking for a place to relax, have a cup of coffee, and read.

The store has a modest book selection and is ultimately forced to sell coffee to stay in business. Still, this is not just a cup of coffee, for it implicitly comes with an experience: the opportunity to discuss books you’ve read, would like to read, or haven’t heard of yet. In Wang’s opinion, this is the single most important element of independent bookstores, one that the chain imitations have no ability to emulate: “people don’t just come to our store to find a book; they come here to find me, to get a recommendation, and drink coffee together.”

Wang’s opinion is no anomaly. Independent bookstores in China use various schemes, such as a book club hosted by Peng or slick WeChat articles from Chengdu-based RosaBooks, to increase their popularity. But ultimately, a charismatic, sociable manager seems to be the most common thread in the tapestry of Chinese independent bookstores.

This phenomenon is perhaps nowhere more clear than Kunming’s Wheatfield Bookstore, where an interview was continually interrupted by customers eagerly trying to get the latest recommendation from owner Ma Li as he explained his understanding of an independent bookstore: “First, the owner needs to personally enjoy reading; second, they need to individually stock the store’s books, picking a selection that fits their personal taste; third, they need to reflect over the content—imbue it with their own spirit.”

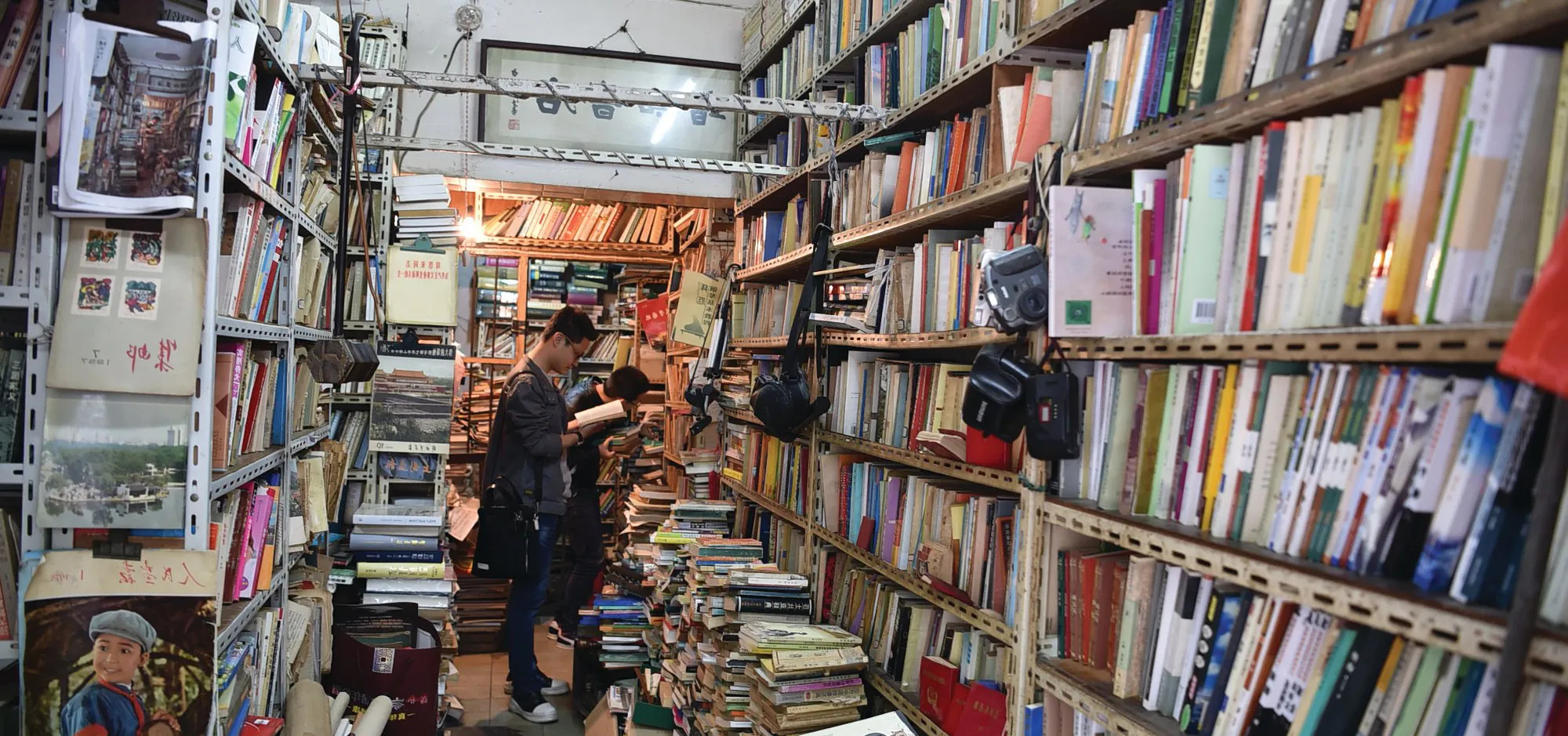

Wheatfield Bookstore and Zhiyuan Bookstore—also of Kunming, owned by the captivating Li Xuntao—provide two interesting snapshots of the culture that makes up independent bookstores in China. Both occupy small spaces jammed with books, both owners were inspired by other independent bookstores in China, and both are supported by loyal clientele, but their owners took different paths to the profession. Ma first worked in logistics before he decided to throw caution to the wind and follow his dream; Li never made it past elementary school, but worked as a blue-collar laborer until his mid-20s when the notion of entrepreneurship took hold of him. Then, with the encouragement of his wife and family, he decided to open his dream store: “when I was in elementary school I realized I liked reading; at that time I would read in the library. So I thought, why not open my own?”

These stores generally seem grounded in an idyllic interpretation of life among books and people who appreciate them—consisting of scintillating discussions with clientele, and lazy hours spent reading when business is slow. This dream was embodied most by Peng, perhaps a sign of young ambition.

Four months after the opening party, the future of One Book Shop was not set in stone: “Maybe I’ll try moving it to a bigger city,” Peng said. “Yangshuo is a tourist place, so there are not many people with similar interests around here.” As for his monthly book exchange, he had reduced the number of copies stocked from around 40 to 20 or less, “it’s not about money, but still so few of them have sold—it’s not ideal.” Such were the fruits of his initial foray at constructing an oasis. But asked if he would continue his idealistic approach to bookstores in the future, he was resolute: “absolutely.”

Bookish Dreams is a story from our issue, “Taobao Town.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.