China’s all-gay reality show has to evade the Big Brother of content regulations

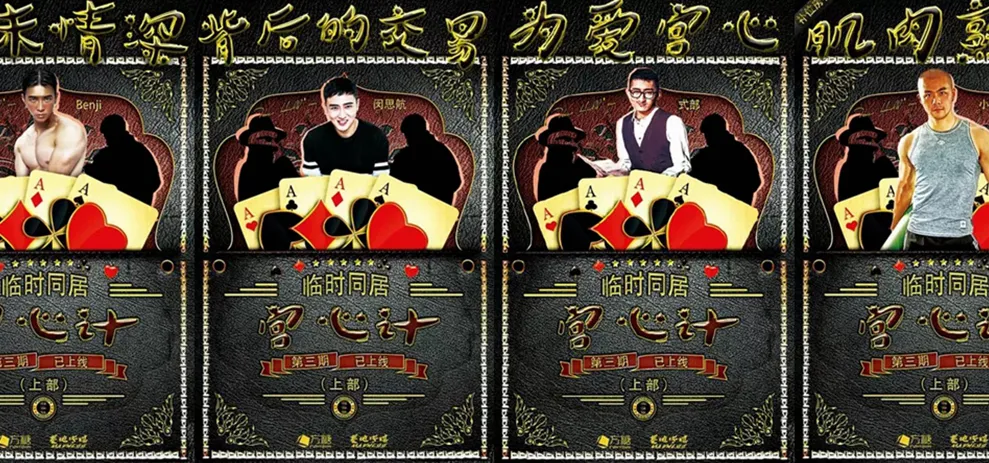

The reality show Stand by Me (《临时同居》) might seem a little familiar: Young participants from all walks of life are invited to share a suburban mansion, where they live together day-to-day, cook for one other, play games, complete challenges in teams, and, like a roommate-rom-com gone wrong, vote off one of the housemates at the end of the episode.

Yes, it’s just the like the classic reality show Big Brother, but what’s different here is that the cast of Stand by Me are all openly gay men.

Broadcast on the mobile app Fantang, the show is only accessible to those who are willing to pay 1.5 RMB for each episode. Though it’s not on TV or any mainstream video-streaming platforms, the show has become very popular. It received a per-episode average of 5 million views and its production company, Madness Culture, says the show has close to a million regular viewers total.

The show, unsurprisingly, defines itself as a niche program. Producers target a young audience, because they consider this audience to be more open-minded. The paywall protects the show from haters, and more importantly, censors. “It’s a small platform, so regulators don’t pay much attention. If we were on [popular streaming platform] iQiyi, we’d be more noticeable,” says producer Sha Yunchun, in an interview with TimeOut.

(Douban)

In China, TV shows and films involving same-sex relationships always run into Big Brother. In 2015, the State Administration for Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT) issued a regulation stating that “TV programs shouldn’t display abnormal sexual relationships and behaviors, such as incest, same-sex relationships, sexual perversion, sexual assault, sexual abuse, sexual violence, and so on.”

Thus, many producers of queer content turned to online platforms, which worked pretty well, at least to start with. Heroin, a web series about romance between teenage boys, was one example. Though the show attracted a great number of viewers after its online migration, it was removed from the video platforms in February, 2016. Afterwards, its audience could only access it on Youtube.

But the censorship hasn’t put off the industry. Due to the inexplicable interest in gay romance from some segments of the Chinese public, the marketing potential of these shows is considerably huge. In order to get streamed, producers exploit many loopholes.

Revive ( 《重生之名流巨星》), a 2016 webseries adapted from an online fiction, is one example. The original story featured a man who died in a car accident and was reborn in the body of another person. But in the webseries, his character didn’t die, but was just disfigured from the accident. After undergoing plastic surgery, he assumed a new identity. The original same-sex relationship between the two leading roles was also changed into a suspiciously close friendship.

Another 2016 webseries, Irresistible Love—Secret of the Valet (《不可抗力之男仆的秘密》) was also based on a novel that tells a romantic story between two men. But when it came to the show, the marketing team avoided of the word “love” in all their promotional materials. Their position is that there is one male character who cares exceedingly about another male character and shows it, but that doesn’t necessarily mean romance; however, if the audience interprets it to be love, so be it.

Love is More than One Word (《识汝不识丁》), yet another series from 2016, was set in ancient China. Adapted from a popular gay romance online novel, most of its audience knew what kind of story they were getting. But if you were to look up the synopsis, you will find: “The story is about a young man born in a rich family trying to become an upright official to comfort his father in heaven.” It emphasizes the always popular and politically correct theme of anti-corruption, avoiding any mention of romance—but being a niche genre, it doesn’t really need to.

It’s understandable that these webseries’ have to stoop to different types of subterfuge to ensure they won’t be pulled off the air. But at the same time, it’s a sign that a more open and inclusive media environment is badly needed. Or else, the drama behind the camera will continue to surpass what goe on in front of it—and that will be really pathetic.

Cover Image from Douban

![[baike.baidu.com]](https://cdn.theworldofchinese.com/media/images/333333333333333.width-800.jpg)